Originally a stretch of open land to the north of the City of London, Bunhill Fields got its name from its use as a burial ground during the Saxon period and a macabre event that took place in the mid-sixteenth century. Cartloads of bones from the charnel house at St Paul’s Cathedral were transported out of the city and dumped in such large quantities that they formed a hill of bones, with a thin layer of soil covering the mound. This “Bone Hill” was large enough to accomodate three windmills on top, which were presumably installed to make the most of the elevated ground.

The charnel house at St Paul’s had been used since the 13th Century to store old bones disturbed by later burials. During this period the concept of purgatory had become an official part of Church doctrine and it became acceptable to disinter human remains when no flesh remained on the skeleton, as it was believed that the soul only remained with the body as long as there was flesh on the bones (cremation was not authorised for Christians at this time). This had a useful practical application as old graves could be reused for new burials, freeing up space in churchyards. The dry bones removed from old graves were then stored in charnel houses and this practice continued in Britain until the Reformation. After the Reformation, the use of charnel houses was seen as Popish so most of them were demolished and their contents removed, which helps to explain why the human remains were removed from St Paul’s and taken to Bunhill Fields.

In 1665, a century or so after the Bone Hill was created, Bunhill Fields was given authorisation to be used as a plague pit. Thousands were dying of plague in London and the rural location of Bunhill Fields, only a short distance north of the city, made it an idea location for mass burials. However, it is unclear whether the site was ever used as a plague pit. It is also unclear what became of the bones from the charnel house of St Paul’s. The land passed into private hands in the 1660s and burials began in what was referred to as “Tindal’s Burial Ground” after Mr Tindal, who had taken over the lease of the land. As the burial ground was not associated with an Anglican church, it became popular with Nonconformists – those Christians who did not belong to the Church of England. A separate burial ground for Quakers was also opened close to Bunhill Fields in 1661 – sadly today very little of it remains due to severe bomb damage during the Second World War.

Throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries Bunhill Fields became the major burial ground for London’s Nonconformists. Robert Southey, a 19th century poet, described it as “the Campo Santo of the Dissenters” as so many influential Nonconformists and their families were laid to rest there. Isaac Watts, a celebrated hymnwriter, is buried in Bunhill Fields, as is preacher and pamphleteer Richard Price, and Thomas Newcomen, a preacher and early developer of steam engines. The mother of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, is also buried in Bunhill Fields, as is a grandson of Oliver Cromwell and the grandfather of JRR Tolkien. The most prominent memorials today are of the famous literary figures of Daniel Defoe, John Bunyan and William Blake.

Daniel Defoe is most famous for writing the novels Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders, but during a prolific career also produced a great deal of pamphlets and non-fiction as well as his famous, pioneering novels. It is thought that when he died in 1731, Defoe was on the run from his creditors. In 1870, the imposing obelisk memorial to Defoe (pictured above) was unveiled. It was funded by an appeal in the weekly newspaper Christian World.

John Bunyan, author of the famous allegorical novel The Pilgrim’s Progress, also has an impressive memorial at Bunhill Fields. Bunyan was a popular preacher, and found himself imprisoned twice for illegally preaching in the years when it was still against the law to belong to a church other than the official Church of England. The Pilgrim’s Progress, which was probably written during his periods of imprisonment, was published in 1678 and has never been out of print since. His impressive memorial, featuring a carved effigy of Bunyan and images representing scenes from The Pilgrim’s Progress, dates from 1862.

William Blake was an artist and poet, who spent most of his life in London. During his lifetime he was considered to be mad, but today he is regarded as one of Britain’s greatest artists and poets, and his work continues to have a considerable influence on popular culture. One of his most enduringly famous works is And did those feet in ancient time, which was adapted into the popular hymn “Jerusalem”. It is uncertain exactly where Blake’s grave lies, as gravestones were moved around when the site was remodelled in the 1960s. None were present when I visited Bunhill Fields to take photographs for this blog post, but Blake’s grave is often adorned with trinkets and flowers left by his fans.

In 1853, Bunhill Fields was deemed to be full, having received around 120,000 burials since the 1660s. Around this time, churchyards and older burial grounds were being closed and large, suburban cemeteries were being planned and laid out. The last burial in Bunhill Fields took place in January 1854.

After the cemetery’s closure, Bunhill Fields was designated as a public park and underwent some remodelling in the late 1860s. Some memorials were removed and many were restored or relocated. The main centre for Nonconformist burials shifted to Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, one of the new cemeteries that made up London’s “Magnificent Seven”. Charles Reed, a directer of Abney Park, was also involved with the preservation of Bunhill Fields and its conversaion to a public garden.

Bunhill Fields as we see it today is a postwar creation – heavy bombing during the Second World War prompted major landscaping work and the northern part of the burial ground was cleared of its memorials, leaving a large grassy area lined with benches, which is popular with workers on their lunchbreaks. The areas containing tightly packed gravestones were fenced off to protect the monuments, and many new trees were planted. Today, the City of London Corporation is making effors to improve the biodiversity of the area by encouraging wildlife and wild flowers to thrive in the burial ground. The peace and the abundance of plant and animal life make a contrast with the office blocks and busy roads nearby.

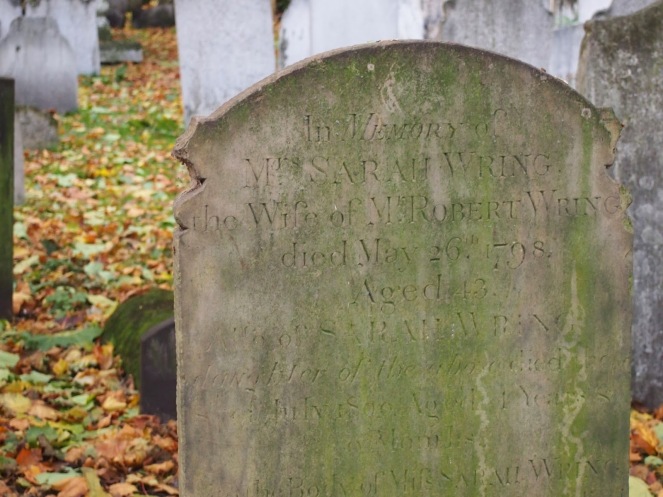

In 2011, Bunhill Fields was designated as a Grade I listed cemetery, affording it special protection. In addition to this, 75 individual monuments are also Grade II listed, and Bunyan and Defoe’s memorials are Grade II* listed. Due to the large number of Nonconformist burials on the site, most of the gravestones are fairly plain and austere, and many of them have become worn and illegible over the years. The gravestones are huddled much closer together in Bunhill Fields which gives it a different feel to big Victorian cemeteries such as Abney Park or Kensal Rise, which were intended from the beginning to serve as parks as well as burial grounds. Bunhill Fields is quite a unique spot – and it is quite mind-boggling to think that 120,000 people are buried on such a small site.

Bunhill Fields is located between City Road and Bunhill Row in London EC1 (the nearest tube stations are Moorgate and Old Street), and it is open all year round. Information about guided tours and access to the fenced-off areas can be found at http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/city-gardens/visitor-information/Pages/Bunhill-Fields.aspx

This blog post was originally published on Historical Trinkets on 31st October 2013.

Oh my. The sight of that marvellous stone with the relief-carved skull on one edge (second and, er, eighteenth photos down) unlocked a door in my memories and out tumbled the introduction to the old Conan the Barbarian novels: ‘Know, O prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of…’ It really has that dark and ancient look 🙂

LikeLike

Funnily enough that’s my favourite of the tombstones at Bunhill and one that always catches my eye as I walk through. It’s so distinctive and really does add to the atmosphere of the place. I like your Conan quote – seems very appropriate 🙂

LikeLike

Excellent and informative article. Used to love making lunch hour pilgrimages to Bunhill Fields to escape the office.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Great article. I came here on April 17 2013 when I just happened to be in London but did not want to experience the mass hysteria that accompanied Thatcher’s funeral. I found it quietly reassuring to be close to the memories of luminaries like Blake, Bunyan and Defoe.

LikeLike

Thank you! Bunhill Fields is a really nice oasis from the madness of central London, isn’t it? I too avoided the hysteria of the funeral that day, but sadly had to see the day out at work rather than in a lovely burial ground!

LikeLike

Hi 🙂 thanks so much for your wonderful site, very informative and the photos are beautiful. I would like to ask a question regarding Bunhill, I visited in August this year. I’d like to know what happened to the rest of it? I imagine that it was originally much larger – were the graves moved/bulldozed? Also, not sure that there could still be 2000 monuments there, unless I missed a big part of the location. I searched for information online, but haven’t been able to find out what happened to it, in terms of down scaling of its size? Any information would be much appreciated 🙂

“It was in use as a burial ground from 1665 until 1854, by which date approximately 123,000 interments were estimated to have taken place. Over 2,000 monuments remain.”

LikeLike

Hi there – I think Bunhill Fields is around the same size today as it was in the past (at its largest extent), and I suspect that there may well be up to 2,000 monuments remining on the site as they are packed very close together. The grassy area with very few monuments is part of the old burial ground but was badly bombed in the war, so the gravestones were cleared. It is quite mind-boggling to think of the number of people buried in such a small area.

LikeLike

You take such beautiful photos. Thank you for giving us these interesting burial ground tours.

LikeLike

Always love these stories. One of the best written blogs, too.

LikeLike

Would love to find a map of how the cemetery is laid out in plots ,like where would this be ExW 87 NxS 52

LikeLike

Hi, I’m not sure if such a map exists but I found this guidance on the City of London’s webpage for Bunhill Fields.

“Records held at London Metropolitan Archives include the interment order books 1789-1854 and the list of those persons whose gravestone inscription survived in 1869. The original registers of burials at Bunhill Fields Cemetery for 1713-1854 are held at The National Archives.”

One of these archives might have the map you’re looking for!

LikeLike

Might be my best bet,but im in New Zealand,lol

LikeLike

I came to this site from Ancestry. One of my relatives from my maternal grandmother side is buried at Benhill Fields.Born 1700 Died 1767. His birth was in Rearsby Leicestershire which after visiting proved to be a charming village. I would love to learn about his life and how he ended up dying in London.

LikeLike

Very good the article on bunhill fields.I was born at my grandparents Dufferin Street, alongside Bunhill Row, in1939. They had to move after bombings end of 1940. Large areas of the city were damaged here and towards At Paul’s and remained derelict well into the late 1950s.

LikeLike