In the shadows of the international terminal at St Pancras Station, close enough for platform announcements to be heard, is a tiny old church which has a history that supposedly stretches back almost as far as St Pancras himself. St Pancras was a Roman martyr who was beheaded in about 304AD for his Christian beliefs, and the church claims that the site has been a place of Christian worship since the 4th Century. Until the 19th Century, Old St Pancras was a rural church, close to the River Fleet, but today it is nestled in amongst the railway infrastructure of St Pancras and the houses and flats of Somers Town. When approaching the church, the first thing that struck me was how high the ground level of the churchyard is compared to its surroundings.

This discrepancy between the ground level of a churchyard and the surrounding area is common in old churchyards and burial grounds – when a burial ground has been used and re-used for many centuries, the ground level rises as more soil is piled on top of new burials. Sometimes this rise in ground level can be quite stark, with the burial ground being several feet above street level.

The church’s own website claims that a place of Christian worship has existed on the site since 314AD. Evidence of Roman activity has been found in the area, which gives some strength to this claim, but no concrete evidence of a Christian site dating back so far has yet been found. It is possible that the church’s dedication to St Pancras dates from St Augustine’s mission to Britain in the late 6th Century – in Rome, St Augustine had lived close to the site where St Pancras had lived and died. A 6th Century altar stone survives at the church today.

The first clear evidence of Old St Pancras’ existence is in the 12th Century, in two land deeds dating from around 1160-1180. Due to the fluctuating population of the area, Old St Pancras went through a number of long periods where the church was little used. The River Fleet, which ran nearby (it is now underground) flooded from time to time and a chapel was built in Kentish Town in the 15th Century so that parishoners living in that area could still attend church when St Pancras was inaccessible due to flooding.

By the end of the 16th Century, Old St Pancras was isolated and falling into disrepair. Topographer John Norden described the church in 1593:

Pancras Church standeth all alone, as utterly forsaken, old and weather-beaten, which for the antiquity thereof it is thought not to yield to Paules in London. About this church have bin many buildings now decayed, leaving poor Pancras without companie or comfort, yet it is now and then visited with Kentishtowne and Highgate, which are members thereof; but they seldom come here for they have chapels of ease within themselves; but when there is a corpse to be interred, they are forced to leave the same within this forsaken church or churchyard, where (no doubt) it resteth as secure against the day of resurrection as if it laie in stately Paules. (source)

As Norden described, the burial ground continued to be used despite the church’s isolation. In fact, during the 18th Century the burial ground was twice extended – which suggests that a lot of burials were taking place there. In 1822 a new parish church (also called St Pancras) was built on Euston Road and Old St Pancras became a chapel of ease. Burials continued at Old St Pancras, however, and a section of the burial ground was used for parishioners from St Giles in the Fields, whose burial ground had become overcrowded and deemed full in the early 19th Century.

By 1848 the church was in a very poor state of repair and was completely remodelled, which saved the building but had some unfortunate consequences. “The historical interest of the ancient building was largely destroyed.” (source) The tower pictured on the 1815 image above was demolished and a new south tower was built, and doors and windows were replaced. The new doors and windows had a Norman-style design, presumably with the intention of hearkening back to the church’s earlier years.

Inside the church, the simple interior contains many features that date from much earlier than the 19th Century remodelling.

Sadly, another feature to be seen inside the church is the presence of a number of large cracks in the walls – a sign of the church’s peril as ancient drains beneath it threaten the building’s stability.

The coming of the railways in the 19th Century had a huge impact on the church in the 1860s – a large part of the burial ground had to be dug up and around 10,000-15,000 bodies were relocated to a mass grave nearby. The burial ground, which had closed to new interments in 1858, was converted into a public park. A young Thomas Hardy was involved in the remodelling of the burial ground – it was he who created the cluster of gravestones that now ring the “Hardy Tree”, which sprang up in the midst of the stones.

In 1882 Hardy wrote the poem The Levelled Churchyard, which rather humourously describes the disturbed burials which were reinterred in a mass grave following their exhumation to make way for the railway.

We late-lamented, resting here,

Are mixed to human jam,

And each to each exclaims in fear,

‘I know not which I am!’…

Where we are huddled none can trace,

And if our names remain,

They pave some path or p-ing place

Where we have never lain!

One of the most famous exhumations from this period was that of the pioneering feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft and her husband William Godwin. Mary Wollstonecraft’s most famous work is The Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Mary and William had lived locally, at the Polygon, and were married at Old St Pancras church in 1797. Mary was to die only months later after contracting blood poisoning following the birth of her daughter, also called Mary. When the younger Mary was in her teens, she would meet her beau Percy Bysshe Shelley at her mother’s tombstone before they ran away together to the Continent. When the burial ground was threatened by the development of the railways, Sir Percy Shelley – son of Mary and Percy – arranged for his grandparents’ graves to be relocated in 1851. Their remains now rest in Bournemouth, but their gravestone remains at Old St Pancras.

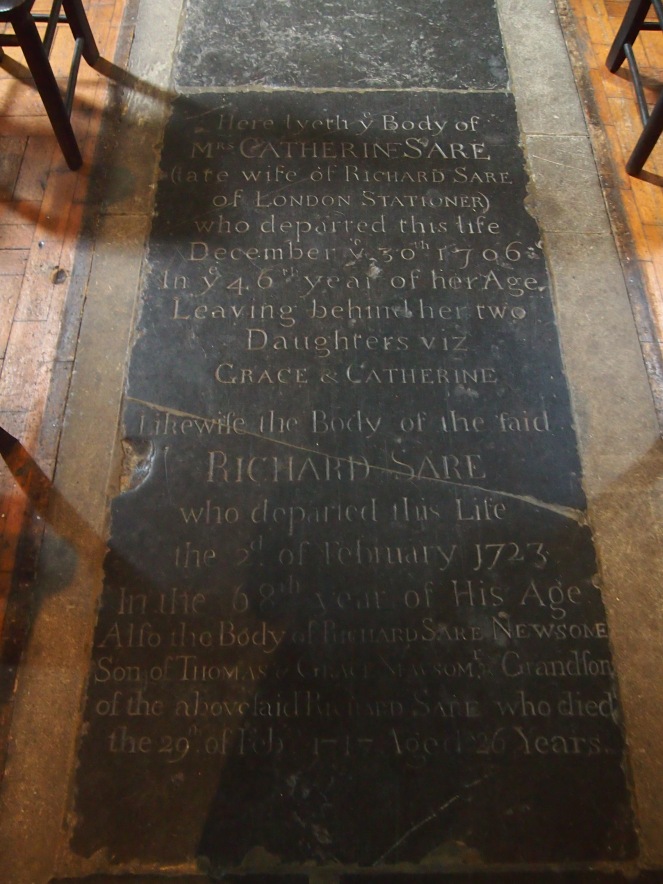

Another wave of exhumations was necessitated in 2002-3, as extra land was needed to accommodate the new Eurostar terminus at St Pancras Station. This was a controversial move, with the media discussing the ethics of disturbing burials to make way for railway infrastructure – a topic that has recently been brought up again with regard to the proposed HS2 rail route. From the burials disturbed by this work archaeologists were able to gain a fascinating insight into a cross-section of the people who had been buried at Old St Pancras. The clay soil and wet conditions meant that many of the burials had exceptionally well-preserved coffins and even inscribed coffin plates, which gave researchers the ability to name some of the individuals exhumed. Amongst these named individuals were a number of French immigrants, who had moved to London after the French Revolution. One of the individuals who was identified was Archbishop Arthur Richard Dillon, who was buried with a fine set of porcelain dentures.

Bizarrely, the archaeologists also found a number of bones belonging to a large walrus. The bones of this huge creature showed signs of being dissected – perhaps it had been used by a scientist for research or a presentation, and then buried later on. Evidence of dissected human remains, found in the trenches where paupers’ burials took place, could possibly point to grave robbery. The mass burial trenches would have been more vulnerable to the attentions of the “resurrection men” than private graves, as it would have been easier to steal remains without detection. In A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens names Old St Pancras as the site of Jerry Cruncher’s grave robbing. The burial ground would have been a prime spot for grave robbery as it was more rural than many of London’s churchyards and not so well guarded.

The burial ground reopened as a public park in 1877, and became known as St Pancras Gardens. Angela Burdett-Coutts, a wealthy banking heiress and philanthropist, paid for a remarkable memorial sundial that commemorated those whose bodies had been moved to make way for the railway. The monument, completed in 1879, has a Gothic tower that resembles that of the nearby St Pancras Station, and the base is decorated with mosaics. It looks a little overgrown these days, but is still an extremely striking structure.

One of the most famous tombs in St Pancras Gardens is that of architect Sir John Soane and his family. Designed by Soane himself, the tomb is Grade I listed and its distinctive shape is said to have inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design for the iconic red phone box. On the top of the dome is a pinecone, an ancient Egyptian symbol of regeneration.

Today, St Pancras Gardens is a peaceful place, far removed from the days of exhumations and body snatchers. The church is part of the Old St Pancras Team Ministry, which also includes other churches in the Camden area. In order to raise funds for the building’s repair, the church has more recently become a venue for lectures and music concerts. After so many years of being a backwater church and chapel of ease, it is encouraging to see this ancient site of Christianity once again at the heart of its community and hopefully the building will be saved for many generations to come.

References and further reading:

“The Clerics, the Resurrectionists and the Walrus”, Ramboll.co.uk, 5th September 2013, http://www.ramboll.co.uk/news/ruk/the-clerics-the-resurrectionists-and-the-walrus-uk

“End of the Line”, Phil Emery, Archaeology UK, May/June 2006, http://www.archaeologyuk.org/ba/ba88/feat1.shtml

“£300,000 appeal launched to save London’s oldest church rocked by high-speed trains and bad drains”, Camden New Journal, 2nd May 2013, http://www.camdennewjournal.com/news/2013/may/%C2%A3300000-appeal-launched-save-londons-oldest-church-rocked-high-speed-trains-and-bad-dr

‘“…The Most Remarkable Woman in the Kingdom.” Or, The Philanthropy of Angela Burdett-Coutts’, The Victorianist, 28th April 2011, http://thevictorianist.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/most-remarkable-woman-in-kingdom-or.html

Wonderful post, so detailed. Thank you particularly for all the pictures.

I think I like the monument overgrown, fits with the gravestones. And I’ll be wondering for a while who did what with that walrus!

LikeLike

Thank you! I really enjoyed exploring the church and burial ground. It was a beautiful day when I visited.

I’d hazard a guess that the walrus was either used for scientific research or exhibited as a “curiousity” (or perhaps both) – but even if either of those are true, I still wonder how on earth it ended up buried at Old St Pancras!

LikeLike

Oo, didn’t know about the walrus. By coincidence, The Beatles did a publicity shoot in the burial ground not long after releasing I Am The Walrus. http://www.beatlesbible.com/1968/07/28/the-mad-day-out-location-five/

LikeLike

I would love to know how the walrus ended up there!

I haven’t seen many of the Beatles pictures from their photoshoot there but I really love that one on your link with the hollyhocks.

LikeLike

great post and a cemetery to add to my list! I recently had chance to visit the Sheffield General Cemetery, a fascinating site and well worth a visit if you ever get chance. I aim to update my blog with a few photos from it in a bit.

LikeLike

Thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed the post!

Sheffield General Cemetery looks absolutely beautiful. I look forward to seeing your photos, and I’ll try to visit it next time I’m in that part of the country!

LikeLike

Sadly it’ll only be 4 or so as I needed to save the film, but yes it is a wonderful site!

LikeLike

Excellent piece of work on St Pancras Church, and very well written by Caroline.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

You haven’t mentioned the fact that St Pancras Old Church was ‘rebuilt’ by R.L.Roumieu and his partner A.D.Gough in 1847-48. I believe some of the changes they made were controversial. R. L .Roumieu was my Great great Grandfather. Would like your comment.

LikeLike

Hi Fiona, although the post mentions the 1848 remodelling of the church I was unaware of who the architects were. They added many features to the church including the Romanesque doorway and windows which weren’t present in the previous church (hence the controversy) but from what I know about Victorian church restorations, their approach was a fairly typical one for the time. Do you know what other churches your Great Great Grandfather worked on?

LikeLike

Thank you Caroline . R.L.Roumieu was also responsible for St. Marks Church and parsonage, Royal Tunbridge Wells. St Michael’s Church, Bingfield Street, Islington,1863-4 and most importantly ,the French Protestant Hospital which was at Victoria Park, Hackney. And many other buildings. His son Reginald St Aubyn as President of the Huguenot Society, unveiled the memorial at Mount Nod in 1911. It is dedicated to Wandsworth Huguenots.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I go past this frequently on the bus…must get off and wonder round sometime..lovely evocative pics

LikeLike

I visited this church in August because my family were involved in its restoration. I wondered if it was possible to download your photos.( I live in Australia) I suspect that is unavailable.

Best wishes Fiona.

LikeLike

Hi Fiona, if you like, I can email you some of the photos I took at Old St Pancras – are there any in particular that you would like to have?

LikeLike

Caroline , It turned out that my photographs are quite good. What I would really like is the history you have researched. Or maybe you could just let me have some of the research sites you used, and then I can look them up for myself. But I expect some of the research sites are only available in England . If it is too much to ask for, I will understand. Fiona.

LikeLike

Good post, nice photographs – new camera? Father James is doing an amazing job on saving the church and money has been raised to stabilise the building and stop the cracking going any further. Hope to see you at London Historians in the spring!

LikeLike

Very interesting (but are you sure it isn’t a pineapple on top of the memorial?).

LikeLike

Thanks!

It’s definitely a pine cone – it was chosen because of its association with regeneration in ancient Egypt.

LikeLike

Thanks for this. I worked in the nearby hospital for years and this was my favourite lunch stop. Staff used it for smokes, meetings and socialising. It was also popular for photographers and historians and this is the best visual account I’ve read.

LikeLike

My first London born ancestors were married here in the 1840s. It’s a lovely spot.

One of the graves in the graveyard has a small brass plated added, near ground level “Name of person was Charles Dickens English Teacher”. I have a photo somewhere.

LikeLike

Thank you for this great write up about the church and for the photos. I have numerous kin buried there, so I can only assume are they now either in unmarked graves or in mass graves. Is there any further information about the archaeological investigation? According to family, a plaque was put up in memory of a family member in the 1820s. Do you know of any listing of the internal monuments?

LikeLike