It’s quite easy to get lost in the maze of highwalks in London’s Barbican Estate, and to some it may be disorientating to discover a medieval church in the middle of the Barbican’s brutalist sprawl. St Giles without Cripplegate is a rare survivor of the Great Fire – even if it didn’t fare too well during the Blitz – and its name is one of the last remaining references to this ancient corner of the Square Mile.

The church’s slightly curious name – similar to many other church names in the City – refers to its site. Any church with the word “without” in its name was situated outside the old city walls, in the case of St Giles outside the Cripplegate. Other examples include St Sepulchre without Newgate, St Botolph without Bishopsgate and the long gone St Ewan within Newgate. Although St Giles is a patron saint of beggars and cripples, the origins of the name “Cripplegate” may lie in the Saxon word “crepel”, meaning a covered passage. Indeed, old documents sometimes use the spelling “Crepelgate”.

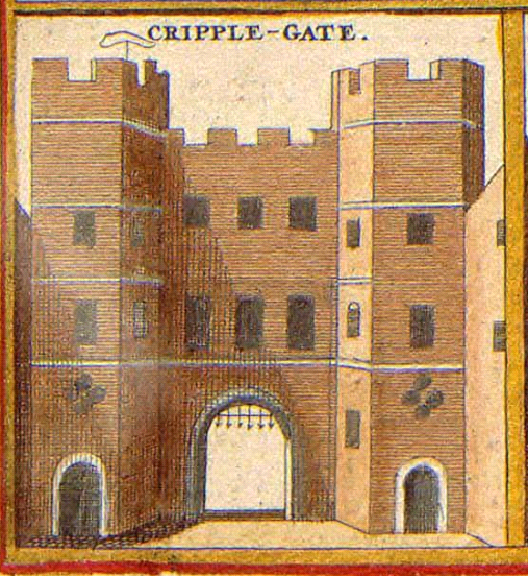

Cripplegate was one of Roman London’s six gates – the others were Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate (Moorgate was a 15th century addition). The Cripplegate initially led into a fort – or “barbican” that served as an extra defence on the northern boundary of the City, but became another of the city’s gates when the barbican was demolished. The 1650 image shown above indicates that there were a number of rooms in the gate’s structure and at different times the gate was used as a prison and as private dwellings. The Cripplegate itself was demolished in 1760, with its materials sold off for £91, a rather large sum at the time. Like many of the old city’s ancient gates and toll bars, the Cripplegate was removed to widen the road and ease traffic congestion. The area of town that the gate had been in retained the name Cripplegate, and to this day the electoral ward for the area is still bears this name.

During the Second World War, the Cripplegate area was particularly badly bombed. By 1951 only 48 people were registered as living within the Cripplegate ward, so widespread was the damage.

St Giles without Cripplegate was built in the late fourteenth century, although there had been a church on the site since the Saxon period, and even before the Second World War the church had had its fair share of misfortunes. Fires in 1545 and 1897 badly damaged the church, but in 1940 the church was repeatedly hit by German bombs and completely gutted, with only its outer walls and tower remaining.

After the war, St Giles was a lone building surrounded by huge areas of bombsite. Although many of its treasures had been lost in the Blitz, the restored church was furnished with items from St Luke’s Church, Old Street, which had been rendered unsafe and abandoned in the 1960s due to subsidence. One monument which did survive the bombing of St Giles was the statue of John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, who lived and died in the parish.

Other notable burials in St Giles were Sir Martin Frobisher, the famed Elizabethan mariner and explorer, and a young woman named Constance Whitney, whose unusual monument – a woman rising from a shroud in a coffin – inspired a chilling story. Attracted by the prospect of a valuable ring on the dead woman’s finger, an unscrupulous sexton opened the coffin – only to get rather more than he bargained for. The story goes that the woman burst out of the coffin when it was opened, having not been dead at all – and that she went on to live to a ripe old age, bearing many children.

This picture of St Giles shows how the church has been rebuilt over the years – by the time of its battering in the Blitz it had already undergone significant structural changes and repairs. The roof area, for example, is noticeably modern but is in keeping with the building’s Perpendicular Gothic style.

Around St Giles, plans were being drawn up for an enormous new housing estate. A large estate, the Golden Lane Estate, had been built in the area immediately north of Cripplegate in the 1950s and in 1965 work began on the estate now known as the Barbican.

The Barbican Estate is built in the Brutalist architectural style, which was popular in the postwar era and was known for its use of concrete – the term “brutalist” comes from the French béton brut meaning “raw concrete”. This use of concrete was the downfall of a number of large housing developments from this period as the concrete used was not of sufficient quality and subsequently, many estates have had to be demolished due to structures becoming unsafe. This was not the case with the Barbican, which utilised a high grade concrete which has not deteriorated over time. The estate was awarded Grade II listed status in 2001 due to its ambitious scale and innovative design – its buildings were connected by highwalks (the “streets in the sky” so often utilised in postwar architecture, with varying success) and the estate also contained many green spaces, including two large lakes. Today the estate remains a popular residential area, with properties changing hands for very high prices.

The Barbican conists of a number of mid-rise blocks and three very tall towers – Shakespeare, Cromwell and Lauderdale – which were, until the Pan Peninsula complex was built at Canary Wharf, the tallest residential buildings in London. The estate is also home to the Barbican Centre, a major arts venue, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the City of London School for Girls and the Museum of London.

Despite being almost fifty years old in places, the Barbican still feels like a very futuristic place. Many examples of “streets in the sky” or brutalist housing estates were failures, either down to poor building materials or ill-thought out design that led to the estates becoming hotbeds for crime and neglect. The Barbican is an unusual example of a scheme that can be seen to have been a success – although its success has come at the cost of considerable gentrification, it could be argued.

In amongst all this retro-futuristic concrete, St Giles without Cripplegate remains. Alongside it are some structures even more ancient than the old church – the remains of part of London’s Roman Wall and its medieval additions.

Several different types of stone and building styles can be seen in the wall, showing how the wall was repaired and strengthened over the years. Several large sections of the old city wall survive in the Cripplegate area – many were exposed by the destruction of the Blitz and today are preserved.

Whether or not Brutalist architecture is your cup of tea – it remains one of the most divisive architectural styles of modern times – the Barbican is well worth a visit, even though it is quite easy to get lost on the highwalks. It is easily accessible from the Museum of London, or from the footbridge from the exit of Barbican tube station. Although little remains of the old Cripplegate area, the surviving ancient church and wall fragments give the estate a sense of what was there before the German bombs fell.

This post has been adapted from a Historical Trinkets post, originally published on 16th January 2012

Reference and further reading

Old and New London: Volume 2, Walter Thornbury, 1878, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45093

Really lovely article – thanks for hosting it!

LikeLike

Thank you Nigel!

LikeLike

Thank you for such an interesting post, love the photos 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you! I really enjoyed taking the pictures – the Barbican is full of wonderful shapes & angles!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love the post – I haven’t been around the Barbican in person for nearly twenty years but this is almost as good as being there 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you very much!

LikeLike

Thanks. Informative and entertaining. I’ll be back to read more here. Regards from Thom at the immortal jukebox.

LikeLike

Thank you Thom!

LikeLike

Interesting, and I like the black and white photography

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks, great article

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

As a student in the 1970’s I was in a hall of residence adjacent to the Barbican, I have always admired the design of the site. As you say it was built to a higher standard than many post war estates and has been better maintained which makes a big difference.

LikeLike

It’s a shame that more housing estates weren’t built to the standards of the Barbican – it’s a wonderful complex and has stood the test of time very well.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on texthistory.

LikeLike

Thank you, great reading. My 5x great grandfather lived at the Barbican and was a police man from 1836-1947, stationed at Newgate prison, the Old Bailey and was an Inspector of City police. I am hope to be visiting this area in 2019 when my sister and I travel from Australia.

LikeLike

Excellent article. Only a little scant on the social detail of the finished product: the name ‘Estate’ for the Barbican is a little misleading, in that it was a high-class development from the beginning. This also partially accounts for its success, and without as much gentrification as one might think!

LikeLike