Among the trees and memorials of Abney Park cemetery in Stoke Newington, a huge white marble lion sleeps peacefully. This beautiful tomb marks the final resting place of one of the great showmen from the turn of the 20th century, “The Animal King” Frank C Bostock. By the time of his death in 1912, Frank’s wildly popular menageries had toured all over Europe and America.

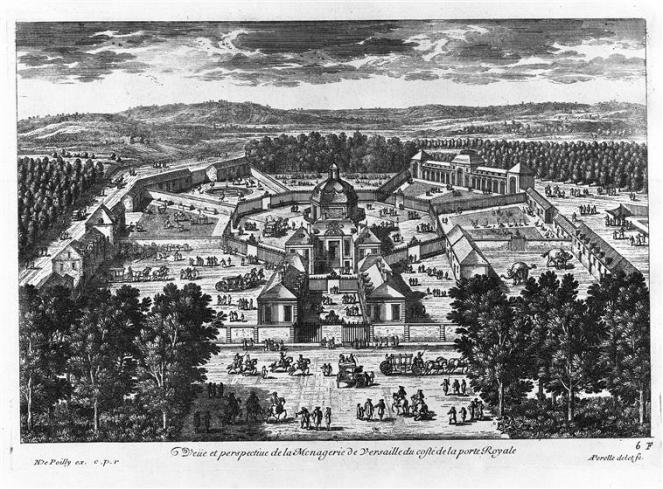

Menageries were originally associated with the very rich, particularly royalty. In the medieval period powerful rulers kept collections of animals and exotic, impressive creatures were often given as gifts from one leader to another. An early example of this is the Asian elephant presented to the Emperor Charlemagne by the Caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, in 797. A menagerie existed at the Tower of London from the 13th Century until 1835. A tower was specially built to house the lions and over the years all kinds of animals and birds from all over the world were brought to the Tower of London, from parrots to rattlesnakes to a grizzly bear called Martin and an owl called Hopkins. During the reign of Elizabeth I, the menagerie was opened to the public for the first time. In the 18th Century, visitors could gain free entry to the menagerie by bringing along a dog or cat to be fed to the lions. Lions were also used for fighting dogs, bulls, boars and other creatures – such fights did not only happen at the Tower of London, but were also widespread in other royal and aristocratic menageries in Europe in the 17th and 18th Centuries. By 1835, the Tower of London’s menagerie was declining and the animals that remained there were rehomed at the Zoological Society of London’s zoo in Regent’s Park. The animals of other royal menageries also got remhomed in zoos when their menagerie closed – after the French Revoltution, the animals in the royal collection at Versailles were tranferred to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which was open to the public and had zoological and botanical collections that could be studied by scientists.

Travelling menageries, which first appeared at the beginning of the 18th Century, brought weird and wonderful creatures to the masses for the first time. Increased trade and contact with far-flung parts of the world meant that it was becoming easier to acquire exotic animals and seafarers often brought such creatures back to their home countries in order to make some extra money by selling them to collectors. Acquiring unusual, exotic animals for their menageries was a coup for any menagerist and was sure to pull in the crowds.

Frank Bostock came from a distinguished dynasty of travelling menagerie owners. His grandfather, the illustrious George Wombwell, was originally a shoemaker but reportedly began his career as a menagerist after purchasing two boa snakes from a trader at the London docklands and exhibiting them in local taverns. From this small venture, George became successful enough to expand his menagerie and founded Wombwell’s Travelling Menagerie in 1810, which toured around the country and eventually consisted of fifteen wagons of animals. His hugely successful shows appeared at the infamous Bartholomew’s Fair in London and even in front of a royal audience. Incidentally, George’s tomb in Highgate Cemetery is – like Frank’s – decorated with a sleeping lion.

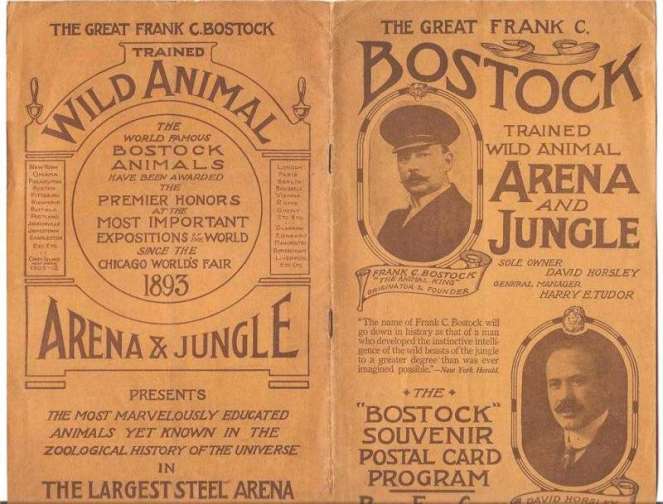

Frank began his career as a showman with his brother as part of the Bostock and Wombwell travelling menagerie, but in 1893 he relocated to America with his new wife and set up on his own. He was quickly a success – working in partnership with the Ferari brothers, his menageries set the standard for shows in America. Frank brought to America the experience he’d gained working with his family’s travelling shows, and also brought the idea that animals should not just be exhibited in cages, but trained and taught tricks in order to maximise their entertainment value.

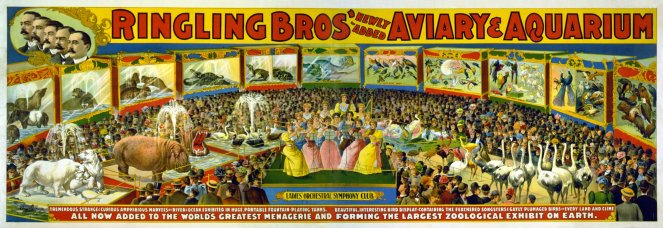

The travelling show was popular in America in the latter part of the 19th Century. Travelling around the country and exhibiting at rural towns, the shows were a combination of animal exhibits, dancing, acrobatics and freak shows, amongst other forms of entertainment. Famous, money-spinning travelling shows such as those of the famous Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey drew in huge crowds to see their vast collections of animals.

Frank’s “Jungles” of performing animals were a runaway success in America. From 1894 one of his Jungles was based at New York’s Coney Island where it consistently got larger crowds than those of his rival, Carl Hagenbeck. Frank was a natural showman – charismatic and apparently well-liked by those who worked for him. He had a large complement of trainers and other employees who remained loyal to him for many years, including the lion trainer Madame Pianka who was well known in her own right and had a highly publicised divorce in 1899. He was also responsible for cultivating the careers of many other great showmen in America, such as George Collins and Percy J Mundy. Frank used his experience to write a book on the taming and training of animals, The Training of Wild Animals, which was first released in 1903 and is still in print today. He mixed with the rich and famous and was reportedly a friend of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Frank returned to Britain in the early 20th Century, bringing big shows to cities all over the country and continuing the success that he had found in America. Bostock’s Jungle was exhibited to great acclaim at Earl’s Court in London in 1908, and Sheffield twice played host to the Jungle in 1910 and 1912.

Frank courted a great deal of publicity, recognising the value in media coverage of his sensational acts. Only months after his arrival in New York, sensational media coverage of the escape of a ferocious lion named Wallace (which had in fact been staged) enabled him to kick start his career in America. Sheffield University’s National Fairground Archive has a number of articles that promote Frank Bostock’s Jungle shows, giving us a wonderful insight into the colourful world of the travelling menagerie in the early 20th Century.

Mr Bostock has hunted and caught wild animals in various countries, but his particular line has been their training after capture. New attractions are continually being sent to his “jungle” centres by agents all over the world. The animals are curious cargo for any ship, but they are carried by special arrangement with the steamship companies. (source)

A most interesting time at the jungle is the feeding hour. The animals devour large quantities of beef and horse flesh, but the elephants, who seem to possess wonderful digestive powers, are anything but epicurean in their tastes. (source)

One article also describes some of women who worked as trainers in Frank’s troupe:

Mdle. Pauline is a plucky lady trainer, her speciality being panthers or pumas. One of them, “Alice”, originally belonged to the daughter of ex-President Roosevelt, and used to roam around the Presidential residence, having all the liberty of a domesticated cat. As it grew older, however, its natural instincts developed, and it was handed over to Mr Bostock for safe keeping. The Polar bears from the Arctic regions have been trained by Mdle. Aurora to present a sketch entitled “The Storming of Port Arthur.” The bears act as artillery men, and fire real guns. (source)

Many times has Mr Bostock been attacked, and his body bears innumerable marks of lions’ claws and teeth, but thanks to a strong constitution and what animal men call good healing flesh, he is to-day none the worse – only richer in his store of reminiscences. (source)

Frank’s lurid tales of capturing and taming wild beasts might sound rather fanciful, especially to cynical 21st Century eyes. However much poetic licence may have been taken in the newspaper articles for the sake of advertising and sensation, the fact remains that Frank did get mauled a number of times over the course of his career and some argue that the serious injuries he sustained on these occasions may have contributed to his death in 1912.

Frank Bostock died on 8th October 1912, aged just 46. Different reports give his death as either being from flu, or from nervous exhaustion. His death at a young age may also have been caused – directly or indirectly – by the serious injuries he sustained on a number of occasions during the course of his work with animals, many of which required hospital stays of many months.

Frank’s funeral was – fittingly for such a showman – a grand affair that brought Stoke Newington to a standstill. Around thirty carriages of mourners followed the hearse to Abney Park, and crowds gathered along the route as a mark of respect. Huge numbers of floral wreaths were sent by well-wishers – the World’s Fair reported that “probably never before has there been such a beautiful collection” (source). Frank’s beautiful tomb still stands out prominently amongst the gravestones of Abney Park, providing a lasting memorial to a great entertainer.

References and further reading

National Fairground Archive, Sheffield University, http://www.nfa.dept.shef.ac.uk/

Frank C. Bostock – The Animal King of Abney Park Cemetery, Stereo Stokey, 22nd Febraury 2009, http://www.stereostokey.com/2009/02/frank-c-bostock-%E2%80%93-the-animal-king-of-abney-park-cemetery/

The Development of Circus Acts, Victoria & Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/d/development-of-circus-acts/

The Royal Menagerie, Historic Royal Palaces http://www.hrp.org.uk/TowerofLondon/Stories/Palacehighlights/RoyalBeasts/RoyalMenagerie

In Pictures: The Sheffield Jungle, BBC Sheffield and South Yorkshire, 23rd November 2010 http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/sheffield/hi/people_and_places/arts_and_culture/newsid_9220000/9220814.stm

It is so interesting to read about the man buried in this magnificent tomb.

LikeLike

Thank you! Before coming across his tomb, I’d never heard of Frank Bostock and it’s been really interesting researching his life and the world he lived and worked in.

LikeLike

The photo of the stone lion and the ferns is marvellous!

LikeLike

Thank you! I didn’t realise I had a picture of George Wombwell’s tomb but fortunately I took some pictures on my phone on a visit to Highgate a few years ago and the one of the stone lion came out very well.

LikeLike

Thank you found this really interesting, what a colourful live and to have died so young, makes you wonder what else he would have achieved if he had lived. Love the tomb, I have never seen one like it before 🙂

LikeLike

It’s such a beautiful tomb – so unusual and so fitting for the man it commemorates. I knew absolutely nothing about Frank before I started researching the story behind his tomb and it’s been fascinating to learn about his life.

LikeLike

That’s the fun part, reserching what you find, amazing what you can still find out 🙂

LikeLike

To learn more about Bostock and many of the other characters laid to rest at Abney Park, come on one of our monthly guided walks, the first Sunday of each month 2pm. No need to book – just meet at the Stoke Newington High St entrance. Free, but please donate if you can to help keep this magnificent memorial park and nature reserve free and open to all. http://www.abneypark.org/what-s-on/walks

LikeLike

Thank you Kirsten – Abney Park is such a wonderful place and I’d definitely encourages as many readers as possible to visit!

LikeLike

Dear Caroline, thank you for quoting the article I wrote in my (now defunct) Stereo Stokey Blog… made me feel quite nostalgic 🤗

LikeLike