Marooned on an island between two busy stretches of road in south west London is a little known burial ground that tells a small part of the long and complex story of London’s immigrants. The name of one of the adjoining streets gives away this connection: Huguenot Place.

The Huguenots were French Calvinist Protestants who left France in search of religious freedom after the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685. The Edict of Nantes had previously granted the Huguenots significant rights in a predominantly Catholic country, but under the more autocratic rule of Louis XIV this tolerance was revoked and many Huguenots saw no option other than to leave France. It is thought that around half a million Huguenots fled to other Protestant countries in Europe and further afield. Many of them settled in England, and today they are most closely associated with the Spitalfields area of East London.

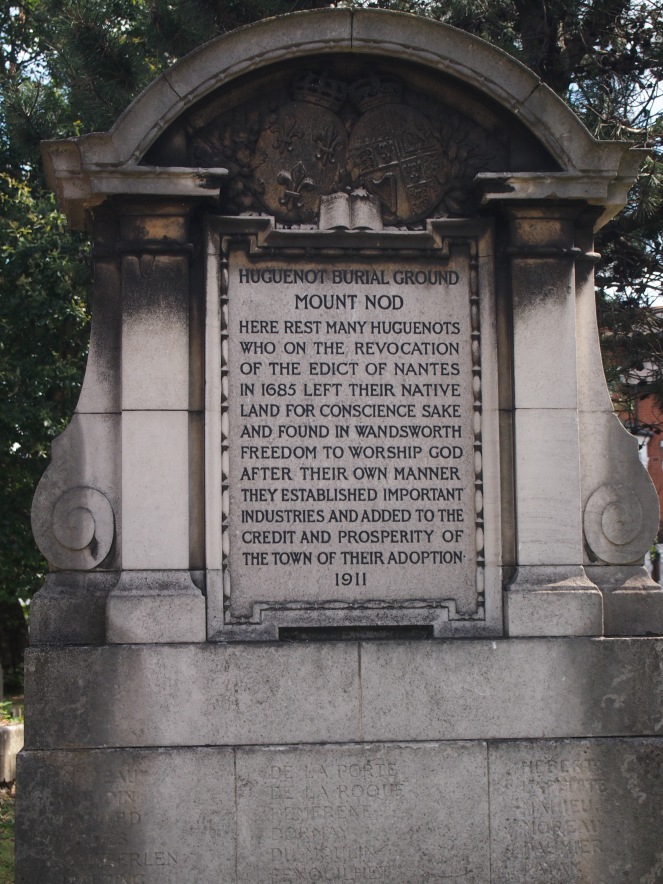

A large number of the Huguenot refugees were skilled craftsmen and many were involved in the weaving trade — which made them welcome in England, as French fashions were popular. The Huguenots who settled in Spitalfields became known for their involvement in the silk trade, but they were not the only Huguenots to settle in London. In Wandsworth, then a village to the south west of London, a community of Huguenots could also be found, with its members involved in brewing, silk dyeing, hatmaking and working in the area’s many market gardens. Church services in French were performed at the old Presbyterian Chapel in Wandsworth for over a century after the first Huguenots arrived. James Thorne, writing in 1876, commented that “gradually the French element became absorbed in the surrounding population, but Wandsworth was long famous for hat making.” As in other parts of England, the Huguenots assimilated with the local populations that they joined and today many Londoners probably have Huguenots amongs their ancestors. A stone, erected in 1911, commemorates the Huguenots buried in the cemetery and remembers their contribution to Wandsworth.

There isn’t a great deal of information to be found about the old burial ground. The name “Mount Nod”, as referenced on the memorial stone pictured above, doesn’t seem to have any obvious origin (at least as far as I can find) – although the site is a fairly significant uphill walk from Wandsworth Town railway station. The burial ground was first used in the late 17th Century, and like so many other cemeteries in London it was closed in 1854 as part of the Metropolitan Burials Act. Today it comes under the care of Wandsworth Council, who replaced the railings around it in 2003.

Frustratingly, when I made my way to Wandsworth on a sunny Saturday afternoon, I was faced with an obstacle: a padlocked gate. A couple of plastic ties on the gate suggested that there had once been an explanation present for the site’s closure, but it is there no more. Luckily, the site is small and with the help of my zoom lens I was able to take some pictures of the old tombs and grave stones through the railings that surround the burial ground. A number of the tombs looked crumbling and unsafe, which probably explains why the burial ground is padlocked.

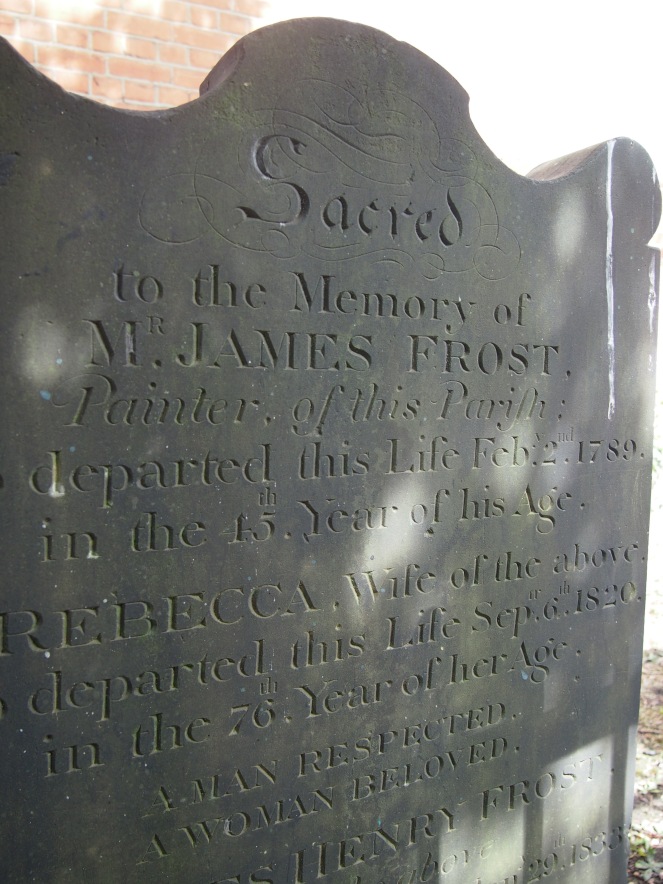

I’m particularly fond of the designs and images present in many 18th Century memorials, and Mount Nod was not a disappointment on this front. One of the tombs, either already restored or simply having stood the test of time better than some of its neighbours, had a fantastic “death’s head” skull and crossbones relief – one of the best I have found so far.

An interesting feature of this burial ground, like so many other 17th and 18th Century burial grounds, is the lack of Christian imagery used on memorials despite the graveyard being a Christian one. Overtly Christian symbolism, such as crosses or images of Christ or saints, were seen as as a Catholic attribute – much in the same way that nonconformist and most Protestant churches lack the often lavish decoration and statues of Catholic churches. Bearing that in mind, it makes perfect sense that Huguenot graves would lack any form of decoration that could be seen as Popish, as they had been forced to leave their homeland by a Catholic regime. Instead, their gravestones feature carved patterns, winged cherubs, the death’s head and other memento mori symbols such as the hourglass, and in the case of some of the grander memorials, family coats of arms. Religious features such as crosses and statues only became popular in the 19th Century, when attitudes towards Catholicism had softened and architectural movements such as the Gothic Revival brought Catholic designs and imagery into the secular sphere.

The concentration of rather grand tombs in such a small burial ground points to a prosperous community. Sadly, many of these monuments are now in a poor condition, either through vandalism or the natural shifting of the ground and tree roots over the years.

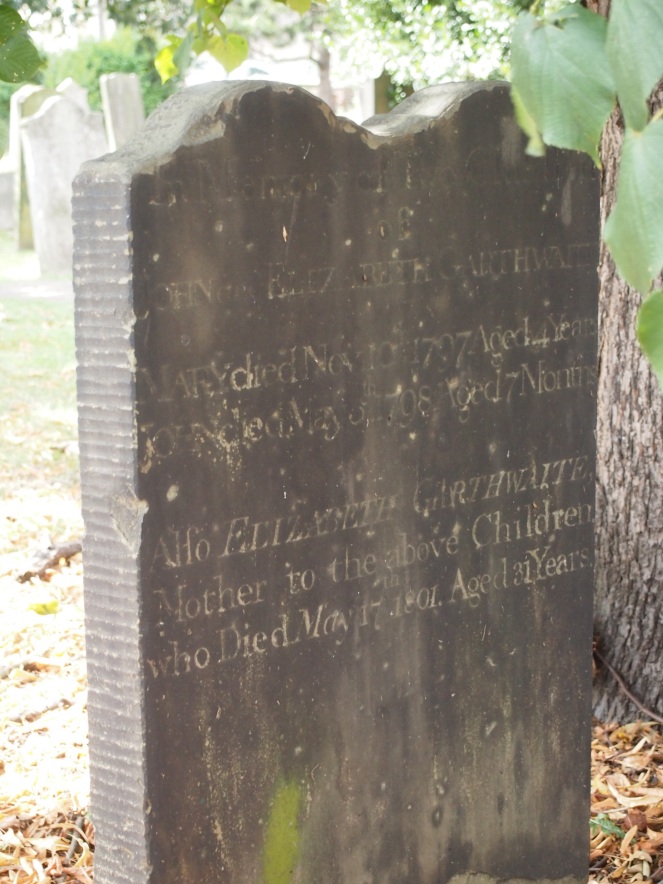

As I wasn’t able to get close to many of the graves, and as many of them were so old and worn, it was difficult to to read the inscriptions on the tombs and headstones. Some of those that were legible showed names that were not recognisably French – these people were not Huguenots, or had over the years Anglicised their names or married into English families. The burial ground opened in 1680, before the Huguenots arrived, and was presumably used by local families as well as Huguenot immigrants. Thorne comments that the cemetery “appears to have been used as the ordinary burial ground for that end of the parish when the Huguenot population began to die out.” Daniel Lysons’ 1792 publication The Environs of London: County of Surrey describes a number of of those buried at Mount Nod, including a number of those buried in the 18th Century with English names, such as Matthew Green, Samuel Goodman and David Asterley. Amongst these English names the Huguenots stand out. James Baudoin from Nîmes, who died in 1739 at the grand old age of 91, had “fled from tyranny and persecution in 1685.” Lysons’ list also includes the wonderfully named Dame Isabeau Bories de Montauban en Guyenne. Other Huguenots buried there included Paul de la Roque, John Delaparelle, Mary Montoileu and Anne Savigny.

This little burial ground is not the only example of a London cemetery becoming associated with a particular expatriate community. At West Norwood cemetery in South London, there is a Greek necropolis which was bought by the Greek community, who settled in London in the 19th Century. It contains many ostentatious tombs, which reflect the prosperity of some of London’s Greek immigrants, and today the necropolis has nineteen listed monuments. (Flickering Lamps will be visiting this beautiful site before too long!)

As well as the grand memorials at Mount Nod, many fragments and more modest grave stones are dotted around the burial ground, some of them surviving from the 18th Century.

When the burial ground closed in 1854, it was redeveloped as a public garden. Over the years, though, the site fell into disuse and disrepair and many of the tombs deteriorated into a ruinous and dangerous condition. In 2010, Wandsworth Council published a document highlighting their intention to restore the Huguenot Burial Ground and reopen it to the public, with plans to add seating to make it a more attractive place for visitors, as well as highlighting the site’s historical significance and refurbishing dilapidated tombs. However, this plan does not seem to have been fully implemented as the gate remains padlocked, although it looks as though the grass areas and trees are cared for. Making safe crumbling tombs and adding some seating would allow local people to interact with and enjoy the space again. In the future, it would be wonderful to see this beautiful resting place of Wandsworth’s Huguenots given the maintenance and prominence it deserves.

References and further reading

England’s “first refugees”, Robin Gywnn, History Today, 1985 http://www.historytoday.com/robin-gwynn/englands-first-refugees

The Huguenots, part of Merton Council’s River and Cloth project, 2010 http://microsites.merton.gov.uk/riverandcloth/textilehistory/huguenots.html

‘Wandsworth’, The Environs of London: volume 1: County of Surrey, Daniel Lysons, 1792 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45394

Handbook to the Environs of London, James Thorne, 1876 https://archive.org/details/handbooktoenvir04thorgoog

Huguenot Burial Ground Management Plan 2010-2015, Wandsworth Council, 2010, http://www.wandsworth.gov.uk/downloads/download/206/management_plans

Great history – it should be taught in schools like this. Making it relevant and interesting. I hope the cemetery is reopened as intended. Thoroughly enjoyable post.

LikeLike

Thank you very much Andrew! I was lucky enough to learn about some of the history of my area at primary school and it definitely really helped me to appreciate my surroundings and their history. I hope that this cemetery can be restored and reopened to the public so that the people of Wandsworth (and further afield) can appreciate and learn from it again.

LikeLike

A fantastic post, I really enjoyed it. I think I wandered round there in the dim and distant past, although as I was killing time before an interview at Wandsworth Town Hall.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s a burial ground I’ve been aware of for quite a long time but although I don’t live very far away it took me a while to get round to visiting. It’s a real gem and I’d be so happy to see it reopened to the public in the future.

LikeLike

The Nod seems to be biblical and refers to wandering, oddly found in reference to the cemetery.

http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/LONDON/1999-01/0915607573

LikeLike

Ah, now that would make perfect sense as a name for a burial ground for refugees!

LikeLike

Fascinating post! I notice that one of the graves is of John and Elizabeth Garthwaite. With it being such an unusual name, I wonder whether they might have been connected to Anna Maria Garthwaite (1690-1763), a famous designer of silks for the Huguenot weavers who had come to live and work in Spitalfields after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. There’s a corporation blue plaque marking her former house at the junction of Princelet – formerly Princes – Street and Wilkes Street in Spitalfields. And a lovely blog about the house by the Gentle Author (April 5th, 2013).

LikeLike

It’s not a common name so I suspect you are correct in linking John and Elizabeth with Anna Maria. I wasn’t aware of Anna Maria’s work so thank you for letting me know about her and pointing me towards the Spitalfields Life post about her home! http://spitalfieldslife.com/2013/04/05/at-anna-maria-garthwaites-house/

LikeLike

Very enjoyable post, thank you. Some of the carving on those tombs is so beautifully executed and has lasted remarkably well (James Frost)

LikeLike

Thank you Nick! It’s amazing how well some of the inscriptions have survived – I’m sure that the stonemasons who created the headstones would be pleased to see how good they still look after 200 years!

LikeLike

My Great Grandfather Reginald St Aubyn Roumieu unveiled the memorial (third picture) to the many Huguenots buried at Mount Nod.on 21.10.1911. He was President of the Huguenot Society.

I wonder if I could have a copy of your article.

LikeLike

Hi Fiona, great to hear from someone with a family connection to Mount Nod! I will email you a PDF version of the article.

LikeLike

For some reason, I never received your PDF , probably due to my ignorance when faced with a computer. Perhaps we could try again? Fiona

LikeLike

Hello Fiona. I have a book with a book plate belonging to your great grandfather “Provence and Languedoc” by Cecil Headlam. Do you know what the connection is with the St Aubyn family is ( I am one of them)?

LikeLike

Lamorna, Sorry I have only just noticed your reply on Flickering Lamps. We don’t know of a StAubyn family. I think it was just the name his parents gave him.I am very interested to hear about the book plate, is it possible to send me a copy. We have a large aschette with his family crest on one edge. But that is about all! Fiona.

LikeLike

It took me a bit of time to find the book! So long ago.. If you email me on lamornagood@hotmail.com, I’ll send you a photo of his bookplate. I did find a bit about him on the web, and I saw that he was an architect, mainly of churches. So was an ancestor of mine in the 19th century but that still doesn’t explain why your great grandfather had our name….curious.

LikeLike

There’s a Mount Nod road in Streatham (used to live on it!), which is named after the farm the land originally belonged to: Mount Nod farm (http://www.ideal-homes.org.uk/case-studies/streatham/3). Still none the wiser as to where the name ‘Mount Nod’ originally came from though!

LikeLike

There are four Mount Nods in South London…the one in this article,one in Battersea (behind Cedars Road,a tumulus now destroyed) the Streatham one,and one in Lewisham (now cleared and rebult as a housing estate)….the origin of the name is not clear,though.

LikeLike

Have been researching my family and found out they were French Hugenots who fled France and went to England. Leonard Henry Jean Vernadeau is buried in one of the Hugenot cemeteries. His son Leonard Vernedeau fled to America (Orangeburg District South Carolina). Appreciate this article on Hugenot cemetery.

LikeLike

Many thanks your photographs and descriptions of this place bought back memories for me ,I lived in Wandsworth when I was a boy in the 1960s and walked past Mount Nod many times on my way to school or to the common and thought it was a calm place amid the noise …really good to see it still there …

LikeLike

Is the Huguenot cemetary in wandsworth now opened to the public. Also would the Huguenot Society have any records for names of people who are buried there?

LikeLike

I am also researching my husband’s Huguenot family. His grandfather wrote that early settlers were buried at Mount Nod Cemetery so I have found this Flickering Lamp site and found it all very interesting. We live in Dorset but would love to visit if it is now possible to gain entrance and would also like to know if there are records of people buried there. Our name is now Botelle and I am sure this has changed over the years, but there maybe a similar name.

LikeLike

Hi. The Mount Nod Cemetery has been refurbished and is now open to the public. The Wandsworth Heritage Library has a small booklet and map listing inscriptions and wills of Huguenots buried there. This was compiled by Mr John Traviss Squire in the late 1880s. You can visit the library to refer to the booklet but it can’t be borrowed though they can make copies of odd pages. Mr Squire gave a talk about his book and it’s appended to the minutes of The Huguenot Society’s meeting and can be read on-line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So good to hear this … Next time I am in London I will visit Mount Nod …

LikeLike

Kia ora I hail from Aotearoa/NZ and my Blackbourne ancestors are interred at Mount Nod (Nod Hill). William Blackbourne (born 1717, died 1796 a victualler), his wife Frances Burbidge (born 1721, died 1788), their daughter Ann Blackbourn (died 1800), son Edward George

They were not connected at all with the Huguenots as far as I know. Is there any other list or information about the non Huguenots who were buried there does anyone know?

Thanks for this fascinating information. I shall caste around for other relatives buried in London to see what other ones I might have a connection with.

Nga mihi (best wishes) Bronwen

LikeLike