Winchester, England’s ancient capital, is home to a great many fascinating old buildings. The area was originally settled in the Iron Age, then became the Roman town of Venta Belgarum and there has been a cathedral in the city since the 7th Century. King Alfred the Great was buried at Winchester and his links with the city are commemorated by an imposing Victorian statue of him in the city centre. Visitors to the city flock to the grand Gothic cathedral and its beautiful cathedral close , the medieval almshouses of St Cross and Winchester Castle’s Great Hall, which is the subject of today’s blog post.

Today, the Great Hall is one of Winchester’s best-known tourist attractions. As the only surviving part of Winchester Castle remaining above ground, over its almost 800 year history it has had many different uses and been witness to many magnificent and turbulent episodes of England’s history.

Originally a stronghold built soon after the Norman Conquest, Winchester Castle later became a royal palace and the Great Hall dates from the reign of Henry III, who was born at Winchester Castle in 1207. The castle had sustained a great deal of damage during seiges during the turbulent reign of King John in the early 13th Century and Henry III added stronger defences as well as a number of chapels and the magnificent Great Hall, transforming it into a grand royal residence.

The primary attraction at the Great Hall is the striking Round Table of King Arthur, which began life as a plain wooden round table in around 1290, built for a tournament held by Edward I, Henry III’s successor. Hosting Arthurian-themed “Round Table” tournaments was popular amongst the royalty and nobility of Europe at this time. The table is built out of English oak and weighs around 1200kg, and has been described as the “greatest symbol of medieval mythology” (source). Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th Century Historia Regum Britannie (History of the Kings of Britain) brought the Arthurian legends to a European audience, and the Round Table was first mentioned in a Norman-language translation of Geoffrey’s work, Roman be Brut by the poet Wace, which was produced in the 1150s. The Round Table was said to have been introduced by Arthur to create a sense of equality amongst his barons – seated at a round table, there were no places that could have been seen as higher or lower than others.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that scientific techniques had developed sufficiently for the table’s age to be ascertained. Radiocarbon dating found that the timber used in the table was felled during the 13th Century, finally putting to bed any lingering beliefs that the table dated from the 6th Century (thought to be the time that Arthur may have existed).

Henry VIII ordered the table to be painted in the distinctive style still seen today – spaces for the knights of the Round Table surround a Tudor Rose, with Henry as King Arthur seated at the head of the table. This was produced in 1522 for the state visit of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and was clearly an attempt to link the power and grandeur of Arthur’s reign with that of Henry.

By the time of Henry VIII’s reign, Winchester Castle had long since ceased to be a royal residence and it is thought that by the fifteenth century only the Great Hall was still being maintained. Winchester itself is described as being “desolate and depopulated” in the later fifteenth century, which perhaps goes some way towards explaining why the castle became less important in this period. However, the Great Hall continued to be used, most notably for the Winchester Assizes, periodic criminal courts that dealt with the most serious cases. The local Justices of the Peace also met there, and Parliament sat at the Great Hall on a number of occasions.

In 1603, Sir Walter Ralegh was tried for treason at Winchester Great Hall. He was accused of being involved in a plot to overthrow King James I, known as the “Main Plot”, which allegedly intended to overthrow James I and replace him with his cousin Arbella Stuart. Ralegh was found guilty, and sentenced to death. This death sentence was reduced at the last minute, and he was instead imprisoned in the Tower of London until 1616. Following a disastrous voyage to Guiana, where he violated a peace treaty with Spain, Ralegh was executed on his return to England in 1618.

The English Civil War almost saw the Great Hall lost forever. After Winchester Castle was captured by Parliamentarian forces in 1649, Oliver Cromwell gave the order for the entire structure to be demolished. There was a risk that if the castle fell back into Royalist hands that it would provide a well-defended base for them, so its demolition removed the threat of a Royalist stronghold being created in the future. However, the demolition was slow to begin and it is possible that this is why the Great Hall survived.

Following the restoration of the monarchy, Charles II had grand plans to redevelop Winchester Castle as a royal residence grand enough to rival that of the French King Louis XIV at Versailles. Christopher Wren, famous as the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral and the great mind behind the rebuilding of London’s churches after the Great Fire of 1666, was commissioned to design this magnificent new palace. In 1683, work began on the palace and the building later known as the King’s House was built, but Charles II died in 1685 and work on the site was halted indefinitely.

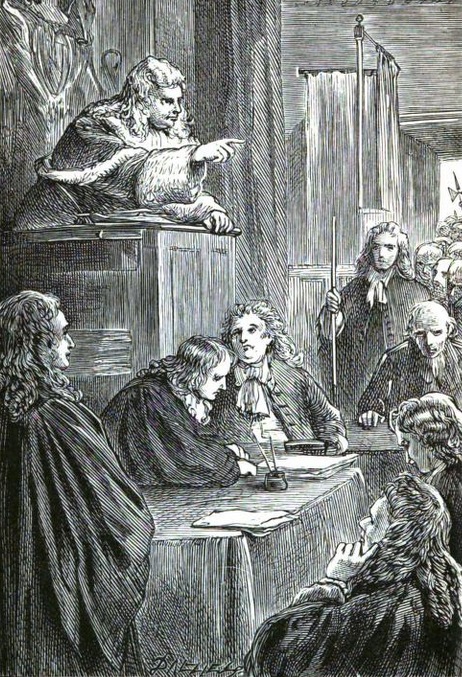

The Great Hall, however, remained the location of the Winchester Assizes and in 1685 followers of Charles II’s illegitimate son, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, were tried there as part of what became known as the “Bloody Assizes”. Monmouth had led a rebellion earlier that year in an attempt to seize the throne from his Roman Catholic uncle, James II. Monmouth and his supporters had been defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor on 6th July 1685, and Monmouth was executed at Tower Hill on 15th July.

Over 1,000 of Monmouth’s supporters were tried over the course of the Bloody Assizes. Overseeing the trials was Lord Chief Justice George Jeffreys, whose role in the Bloody Assizes earned him the moniker “The Hanging Judge”. Many of those tried were sentenced to death, including Dame Alice Lisle, who was beheaded in Winchester’s market place on 2nd September 1685 after being found guilty of harbouring fugitives. It is thought that several hundred men found guilty at the trials were transported to the West Indies, where they were used as cheap labour. The Bloody Assizes moved from Winchester to the West Country, finishing at Taunton, where the bodies of executed men were displayed to deter anyone else thinking of defying the king.

The grand palace built for Charles II never became a royal residence – although the shell of the King’s House had been built it remained unfinished and for many years it lay empty. Queen Anne attempted to complete it, but after the death of her consort Prince George of Denmark the money could not be found. Eventually, the King’s House became a prison. In 1756, the first prisoners of war arrived at Winchester and over the next forty or so years the King’s House was used to hold captives from France, the Netherlands, Spain and America. In 1792, the King’s House was converted to an army barracks and the site was used for this purpose until the 1980s.

In December 1894, a fire broke out in the pay office at the barracks. The King’s House was consumed by the flames and the Great Hall was also threatened by this terrible fire, but efforts were made to contain the spread of the fire and luckily the Hall was saved. However, the King’s House was burned beyond repair and had to be demolished, with it later being replaced by new barracks buildings built in a similar style to the old King’s House. Today, this building has been converted into residential flats.

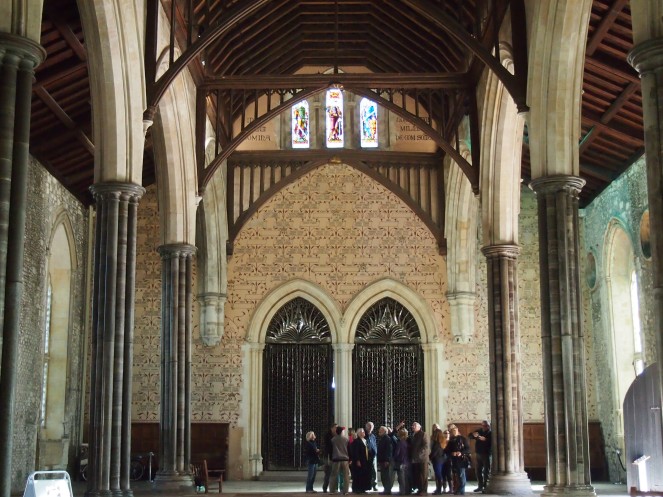

Following the construction of a new court building for Winchester, the entire structure of the Great Hall underwent a significant amount of restoration in 1874, with a new roof being added and some of the stonework in the building being replaced. The restoration sought to remove 18th Century “indignities which had been offered to the old Hall” and restore the 14th Century Gothic features. It was also at this time that the Round Table was moved to its present position, which presented an opportunity to study it more closely – it was while the table was being moved that it was first discovered that it had begun its life as a twelve-legged table rather than something originally designed to be hung on a wall.

A distinctive feature that was added to the Great Hall at this time was the decoration on the wall facing the Round Table, which features the names of Winchester’s Knights of the Shire and members of parliament from the 13th to 19th Centuries.

Another addition made at this time of restoration was the installation of the present stained glass windows, which depict the heraldic arms of various figures important to the history of the county of Hampshire. These spectacular windows were produced by John Hardman and Co, who had produced the stained glass windows for the Houses of Parliament.

During the Victorian period, there had been a resurgence of interest in both the medieval period and the Arthurian legends. The poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson played a significant part in this revival – works such as The Lady of Shalott and Idylls of the King captured the public’s imagination and were enormously popular. The appetite for medieval romance is also reflected in some of the architectural fashions of the Victorian period – the Gothic Revival hearkened back to the spectacular architecture of the Middle Ages. The taste for medieval designs and imagery can be clearly seen in the restoration of the Great Hall at Winchester, which sought to accentuate the building’s early Gothic architecture and decorations which featured medieval kings, knights and coats of arms.

Today, the Great Hall still plays a part in Winchester’s civic ceremonies. It has been the seat of what is now known as the Hampshire County Council since 1889, and the buildings in the vicinity the Great Hall are the administrative buildings of the council. There is also a small but rather excellent museum adjacent to the Great Hall that contains an exhibition of the history of Winchester. In 1897 a statue of Queen Victoria was installed in the hall, and in 1981 a pair of wrought steel gates were installed to commemorate the wedding of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer.

As well as being a major tourist attraction, it is also a popular venue for weddings, and is often home to exhibitions and concerts. At one side of the Great Hall is “Queen Eleanor’s Garden”, a reconstruction of a medieval garden as it might have looked at the time of Queen Eleanor of Provence, consort of Henry III.

After almost 800 years the Great Hall remains at the administrative centre of Winchester. Although its royal connections have diminished over the centuries, this amazing building has over the years witnessed sessions of Parliament, lavish diplomatic visits, high-profile trials and grand civic ceremonies. King Arthur’s Round Table, which takes pride of place, is a dramatic and rather awe-inspiring artefact, and even though it has been proved to have no link whatsoever with King Arthur it has a fascinating history of its own, giving us an insight into how the Arthurian legends influenced and inspired the kings of the medieval and Tudor periods.

Visitor information can be found here.

References and further reading

A History of the County of Hampshire, Volume 5, William Page (editor), 1912 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42041

The Great Hall: Home of the Round Table, Hampshire County Council http://www3.hants.gov.uk/greathall.htm

King Arthur’s Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation, Martin Biddle, Boydell Press, 2000

The Trial of Sir Walter Ralegh: a transcript, Mathew Lyons, 18th November 2011 http://mathewlyons.wordpress.com/2011/11/18/the-trial-of-sir-walter-ralegh-a-transcript/

Dame Alice Lisle: first victim of the Bloody Assizes, Executed Today, 2nd September 2009 http://www.executedtoday.com/2009/09/02/1685-dame-alice-lisle-first-victim-of-the-bloody-assizes/

Winchester Palace, Winchester Museums http://www.winchestermuseumcollections.org.uk/index.asp?page=item&mwsquery={collection}={topics}AND{Identity%20number}={Winchester%20Palace}

Really interesting piece. I’ve been to Wincester and I didn’t find out all that you’ve written here.

LikeLike

Thank you! I really enjoyed visiting Winchester and it was fascinating to research more about this amazing old building.

LikeLike

Great post, Caroline. I love Winchester. I was especially taken by that story of the diver who risked his life to save the cathedral from sinking, by diving into wells in complete darkness.

LikeLike

Thanks Matt!

LikeLike

Fantastic post!

LikeLike

Thank you Sheldon!

LikeLike

Love this place! I used to work in Winchester, and remember it well. That table is magnificent.

LikeLike

I absolutely love the round table – it’s amazing how it’s survived for so long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

is there any info on the hurlbertt or hulbert family there at Winchester please let me know

LikeLike

Hi Dave, I’m not sure if there is any information held at Winchester but someone at the Hampshire Record Office might be able to help you http://www3.hants.gov.uk/archives

LikeLike

A correction: The present county council is Hampshire County Council, originally created in 1889 as the ‘County Council of the County of Southampton’ (the former title of Hampshire). The original name of the county is perpetuated in the badges which are carved in the stonework of the adjacent county buildings with the latin words ‘Com. Southton’. The badge, a rose surmounted by a crown, with the latin inscription was originally used by the County Justices.

LikeLike

Thanks Rowland – I have made the correction.

LikeLike

Another piece of information: The spectacular bronze statue of Queen Victoria is by Sir Alfred Gilbert, famously known for his statue of ‘Eros’ in Piccadilly Circus, London.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s a wonderful statue – I had no idea there was a link with Eros.

LikeLike