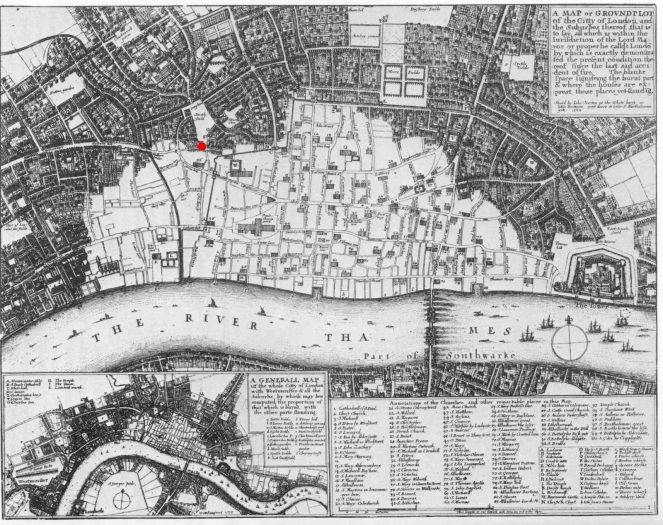

Pye Corner, the site where the Great Fire of London famously came to an end in 1666, has a long and grisly history of which the Great Fire is only one chapter. Accounts of the Great Fire tell us that the Fire began at a bakery in Pudding Lane and ended three days later (having consumed 13,000 houses and 87 churches) at Pye Corner. Christopher Wren’s towering Monument to the Great Fire of London is close to Pudding Lane, but where is Pye Corner?

Pye Corner (occasionally referred to as “Pie Corner” in records) lies just outside London’s ancient city walls, and today is on the corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane, close to St Bartholomew’s Hospital – today, however, the name Pye Corner has passed out of use. It is possible that Pye Corner is situated over the western Roman cemetery (Roman burials always took place outside the city walls) but archaeologists digging on a site very close to Pye Corner in Giltspur Street in 2011 found no Roman burials, instead finding a hitherto unknown part of St Sepulchre without Newgate’s burial ground, with burials dating from the 12th and 13th centuries. Roman burials have been found on nearby sites at St Bartholomew’s Hospital and West Smithfield.

The Great Fire of 1666 was not the first large conflagration in this part of town. Medieval London consisted mainly of buildings with wooden frames, and the risk of large, fast spreading fires was a very real one. On Pentecost 1135 (some records say 1133), a fire burnt a large section of London. Information about this fire is scarce but its extent is said to have been from London Bridge in the east to St Clement Danes, Westminster, in the west. St Sepulchre without Newgate, close to Pye Corner, is first recorded in the years after this fire and from that one can speculate that the church was founded as part of the rebuilding of the city after the devastating fire.

Whether Pye Corner was known by that name in the 12th Century is unknown. Like many place names in London, the name “Pye Corner” probably comes from the name of a pub – the Maypie, or Magpie (reference). In the medieval period few ordinary people could read and write so this pub would have been indicated by a sign or small statue depicting a magpie.

As the Great Fire tore through London in September 1666, buildings were pulled down or destroyed with gunpowder to create fire breaks in an attempt to stop the conflagration spreading further. The fire had broken out on Sunday 2nd September and by Wednesday 5th September it finally burnt out at Pye Corner after the strong winds that had been fanning the flames had dropped and many firebreaks had had been created by demolishing buildings.

At the time of the Great Fire, anti-Catholic sentiment was widespread and many people sought to blame the fire on a “popish plot”. Scapegoats were sought and a French man, Robert Hubert (sometimes described as having had learning difficulties), was executed for starting the fire, despite reports that he had not arrived in London until two days after the fire had started. Christopher Wren’s Monument, situated close to where the fire broke out at Pudding Lane, even included a bold inscription stating that the fire was started by “the treachery and malice of the Popish faction”. This section of the inscription was removed in the 1830s, when attitudes towards Catholicism had changed significantly.

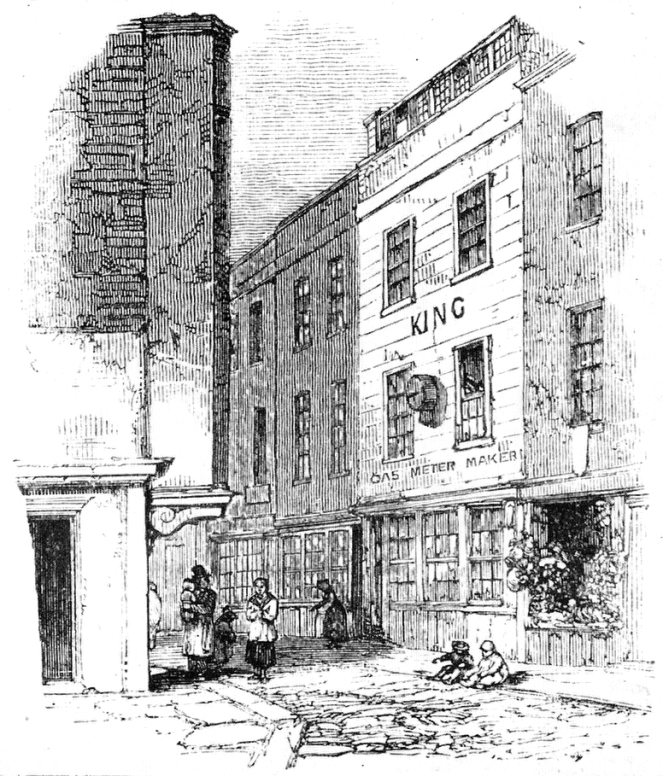

The memorial to the fire installed at Pye Corner, on the other hand, was far removed from the grandeur and (now removed) sectarianism of the Monument. A statue of a cherub or young boy, around two feet tall, was attached to the wall of the building on Pye Corner. Exactly when the statue was put up is unclear – this image from the Museum of London dates from 1791. Rather than blaming Catholics for the fire, the inscription on the cherub reads “This boy is in Memory Put up for the late Fire of London, Occasion’d by the Sin of Gluttony, 1666”. It is likely that this conclusion was reached because of the sites where the fire began and ended – Pudding Lane and Pye Corner. (Pudding Lane, incidentally, was not named after any tasty foodstuffs but for the “puddings” of entrails and other waste from butchered animals that fell off the carts that went down the lane on their way to dispose of the remains.)

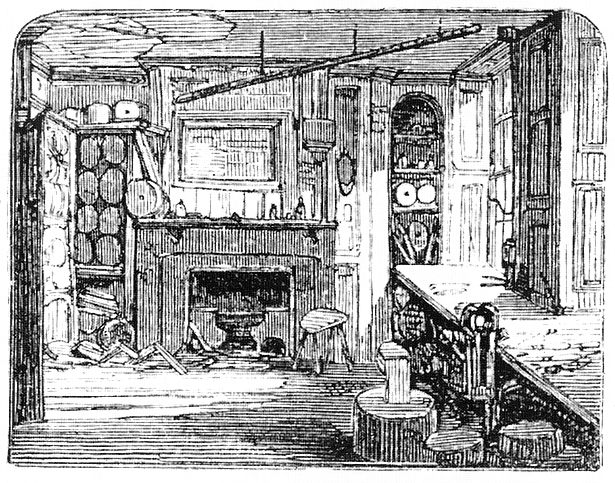

The cherub was built into the front of a pub on Pye Corner, the Fortune of War – which has a notorious history of its own. Its proximity to St Bartholomew’s Hospital meant that it was an ideal base for resurrectionists – better known as bodysnatchers. In the 18th and early 19th centuries there was a shortage of cadavers available for dissection by medics and large sums of money could change hands for fresh corpses, many of which were illicitly dug up by bodysnatchers as soon after burial as possible (although there are also cases of people being murdered – sometimes to order – and their corpses being sold for dissection). People feared the theft of their loved ones’ bodies so much that families would pay guards to watch over graves until the body was too decomposed to be of interest to bodysnatchers, and at St Sepulchre’s church close to Pye Corner a Watchhouse was built to deter bodysnatchers. The role of the Fortune of War pub in this grisly business was to provide a place where bodies could be brought in and assessed for suitability by medics from the nearby hospital.

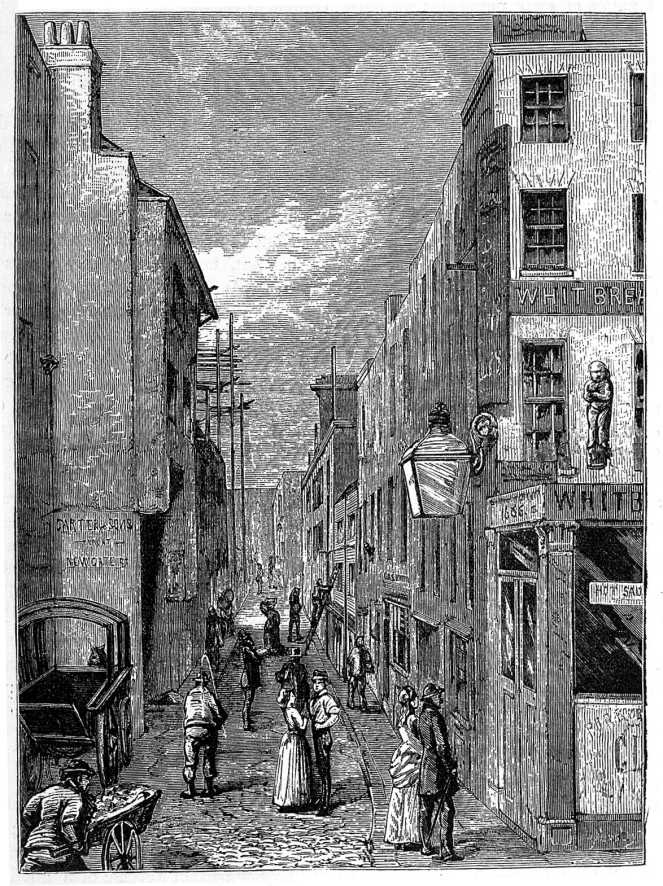

The rather amusingly named Cock Lane is one of the two streets that meet at Pye Corner – its name is thought to originate from the old popular sport of cockfighting, a cruel sport where the birds were trained to fight each other to the death. The street was also home to the only legalised brothels north of the Thames. However, Cock Lane is most famous for an incident in the early 1760s when a haunting was reported at one of the houses on the street.

The first reports of paranormal activity began when a couple, William Kent and Fanny Lynes, who were living as man and wife (William had previously been married to Fanny’s sister Elizabeth, who had died in childbirth, and laws at the time prevented him legally marrying his dead wife’s sister) lodged at the house. The man who offered the couple lodgings was Richard Parsons, a clerk at nearby St Sepulchre’s church. Kent loaned Parsons (who was known by local people to be a drunk) 12 guineas, despite the fact that his previous landlord in London had refused to repay money he owed Kent after learning that he was not married to Fanny.

Fanny became pregnant and Parsons’ eldest daughter Elizabeth, aged around 11, was enlisted to stay with her when William was away. They began to report hearing scratching and tapping noises in the room they were sleeping in. However, in the weeks before Fanny was due to give birth, she and William moved out of the Parsons’ house due to a dispute over the money Parsons owed William, and into lodgings nearby. Fanny was taken ill and died of smallpox. She apparently had taken care to ensure that William – rather than her family, who had disowned her after she began a relationship with William – received all of her money in her will.

William sued Richard Parsons in January 1762 for the money that Parsons still owed him. Around this time, reports of mysterious goings-on at the Parsons’ house resumed. Rumours started to go around that the house was being haunted by Fanny’s ghost, and the girl Elizabeth, who had looked after Fanny during her pregnancy, was particularly affected by the disturbances. It was reported that Fanny’s ghost had returned because she had not died of smallpox but due to foul play, and that William Kent was responsible for her death. The rumours quickly spread around London and became a major topic of conversation and speculation amongst all social classes, with Kent widely suspected as a murderer.

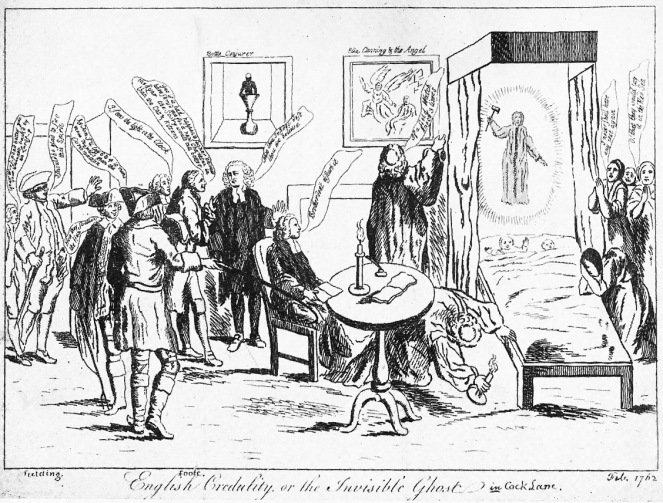

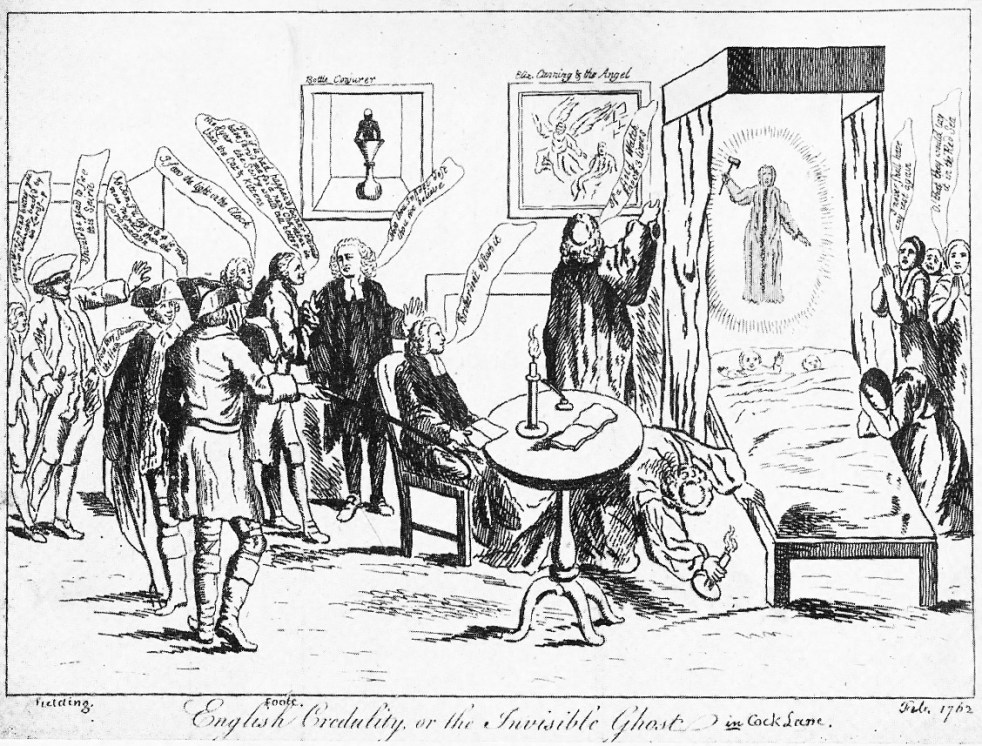

A number of respectable figures, including clergymen, visited the Parsons’ home to attend seances at the house. The ghost was said to communicate with the girl Elizabeth by knocking – for example, the ghost would reply to a question with one knock meaning “yes” and two knocks meaning “no”. Crowds of people soon began to gather on Cock Lane and Mr Parsons charged people to visit his house to witness the haunting for themselves.

However, not everyone was convinced that the case was genuine. A committee, one member of which was Samuel Johnson, was assembled to investigate the alleged haunting. The hoax was finally revealed when the “ghost” claimed that, to prove it was genuine, it would knock on the coffin of the deceased Fanny Lynes at a particular time. The committee duly visited the vault at St John’s, Clerkenwell, where Fanny had been laid to rest, and no knocking noise was forthcoming from her coffin. The ghost was denounced as a fraud.

It was discovered that Elizabeth had been hiding a small piece of wood about her person to create the scratching and knocking noises, and although she was later cleared of any wrongdoing – being deemed an unwitting accomplice – her father was jailed for two years, as well as being sentenced to three days in the pillory. It was deemed that he had set up the hoax to discredit William Kent, the man he owed money to. His wife and a servant were also given prison terms after being found guilty of involvement in the scam. The case became known as “Scratching Fanny of Cock Lane.”

Today, it’s not clear whereabouts on Cock Lane the Scratching Fanny hoax took place. The street is now lined with modern buildings, with a few at the Snow Hill end of the street dating from no earlier than the Victorian period.

If it wasn’t for the Golden Boy being retained on subsequent buildings on Pye Corner after the Fortune of War pub was demolished in 1910, it’s possible that Pye Corner could have been forgotten altogether today, as the name itself has passed out of use and is not shown on maps. As it is, the site tends not to fall under the tourist radar unless it’s included in a guided walk, or stumbled upon by chance whilst visiting other landmarks in the area such as the memorial to William Wallace at Smithfield. The Golden Boy is a far more low key memorial to the Great Fire of London than its Pudding Lane counterpart, the Monument, but as the area also has connections with bodysnatchers and ghost hoaxers, for those interested in some of the darker aspects of London’s history the site is still well worth a visit.

This post is adapted from an article originally posted on Historical Trinkets on 7th February 2012.

That’s fascinating, thank you.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

Scratching Fanny of Cock Lane?! Sounds like a Carry On film with Sid James and Hattie Jacques. Very enjoyable yarn, thank you.

LikeLike

You’re welcome, glad you enjoyed the post!

LikeLike

I wish I’d known about Pye Corner when I worked in the area! I’ll have to pop along for a look next time I’m down that way!

LikeLike

It was through working in the Smithfield area that I first discovered the Golden Boy of Pye Corner!

LikeLike

Love this post (and your site). I also used to work in the City of London and regret I didn’t pay more attention to its history and the buildings.

LikeLike

Thank you! The City is such a fascinating place and I feel lucky to work in an area where there’s so much history. Sadly there never seems to be enough time to explore everything!

LikeLike