A couple of weekends ago, I was invited to attend an event being held as part of the London Month of the Dead at Brompton Cemetery in west London. The main cemetery entrance is on Old Brompton Road, not far from Earl’s Court station, in that slightly ragged edge of town where Chelsea, Fulham and Kensington meet, and where genteel houses make way for seedy hotels and dreary bedsits with grimy windows. Behind high railings, and through an imposing gateway, is one of London’s Magnificent Seven cemeteries.

I’ve visited Brompton several times over the last couple of years, seeing it in all sorts of weather – a damp spring afternoon, a hot and busy open day in the middle of summer, and – most memorably – on a bitter, snowy day where the whole scene was in shades of white, grey and black, with only the red neon lights of Earl’s Court Two glaring through the bare trees. But autumn is my favourite time to explore cemeteries – there’s something about the colours, the softly falling leaves and the gentler sunshine of pleasant autumn afternoons that adds real atsmophere to the exploration of a burial ground.

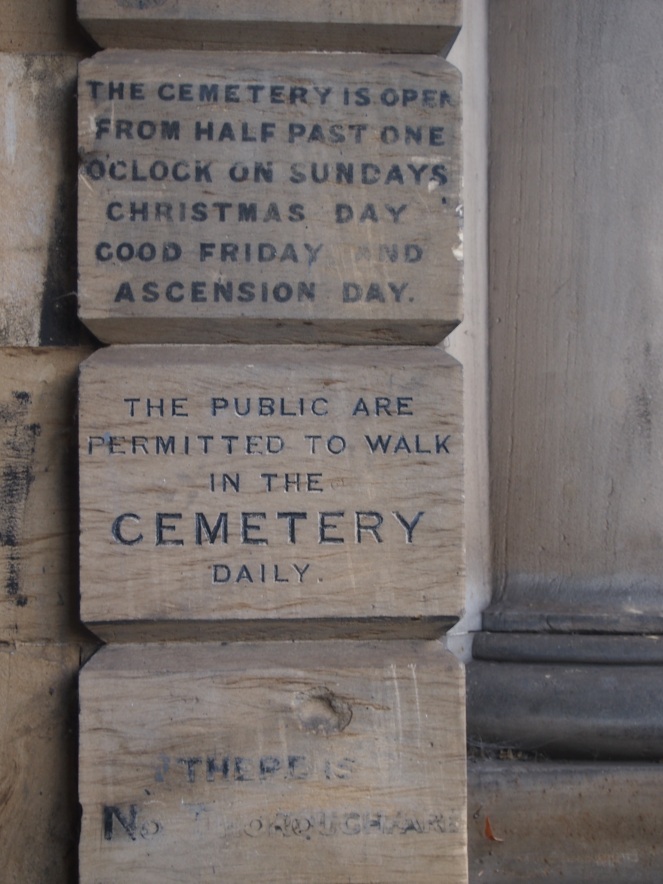

Brompton is a truly beautiful cemetery – it is one of those large, landscaped burial grounds that opened in what was then on the edge of London in the first half of the nineteenth century as an alternative to the choked, overcrowded churchyards in the inner city. Founded by a private company and originally known as the West London and Westminster Cemetery, Brompton was opened to burials in 1840. It has a formal layout, with many long, straight paths. The impressive collonades in the centre of the cemetery are arranged in such a way as to imitate the shape of a magnificent medieval cathedral, a cross shape with a transepts and a central nave, which ends at the door of a beautiful domed chapel which was inspired by St Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Originally, it had been planned to have three chapels at the cemetery, with the two additional chapels at the end of the “transepts” – one for Nonconformists, and one for Roman Catholics. However, these plans never came to fruition. This wasn’t the only problem encountered in the early years of Brompton Cemetery – the project cost more than double what had been initially estimated, and architect Benjamin Baud sued the cemetery company after being dismissed due to the project’s delays and a reported lack of quality in the building work.

The event I was attending was held in the chapel – a small building, with a simple, circular interior. The ceiling, however, is something else. Richly decorated, it is inspired by the grand dome at St Peter’s in the Vatican. There is some peeling paint, but money recently awarded to Brompton Cemetery by the Heritage Lottery Fund will help to pay for the chapel’s restoration.

It’s perhaps a little surprising to see a chapel so inspired by a famous Catholic basilica in a cemetery largely designed for Protestants. After many years of gradual reforms, the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829 had given Catholics the right to vote and anti-Catholic sentiment, which had been high during the time of the Jacobite uprisings in the 18th Century, was on the wane. In the 19th Century, around the time that Brompton Cemetery was being planned and built, many figures within the Anglican church were reacting against developments in the Protestant church and looking to Catholicism to inspire a return to lost traditions. Known as the Oxford Movement, members of this movement believed that the Church of England was not a Protestant church but a branch of the the historic Catholic church. This belief ushered in a period known as the “Catholic Revival”, and the acceptance of Catholic rites and practices into Anglicanism came around at the same time that the Gothic revival – architecture inspired by medieval religious buildings – became popular. It is therefore unsurprising to see gravestones and memorials with Catholic-influenced designs. Catholic imagery abounds in many of the memorials in the cemetery – there are many Celtic crosses and a few depictions of the crucified Christ, an image that – only a few decades before – would have been seen as popish and unacceptable.

Unlike many other new cemeteries opened in the 19th Century, Brompton did not remain in private hands for long. The cemetery had cost a great deal of money to build and set up, and by the 1850s its shareholders were not seeing the returns on their investments that they had wished to see. Under the Metropolitan Interments Act of 1850, the cemetery was nationalised.

In this respect, Brompton has been lucky. Unlike so many privately-owned burial grounds, which went bankrupt after the Second World War and became derelict and vandalised – by thoughtless local councils as well as youths – Brompton has remained quite well-managed. Today it is managed by Royal Parks, which makes it Britain’s only Crown cemetery.

Parts of the cemetery are quite overgrown with bracken and brambles, but these areas of greenery provide a good habitat for wildlife. The recently proposed plans to restore and improve the cemetery involve planting new trees, shrubs and flowers and surveying the cemetery’s wildlife, as well as converting existing buildings into a visitor centre and setting aside an area for children to explore the site’s flora and fauna.

The collonades in the centre of the cemetery are probably the most striking feature of the site. Beneath the collonades are catacombs, with room for thousands of burials. The catacombs, however, were not a success and only around 500 interments were ever made in them. I visited the catacombs on the cemetery open day in 2012 – they follow the same lines as the collonades, narrow corridors with coffins stacked neatly on either side. When I visited, they were lit only by candlelight. There was something quite odd about standing in a dim space surrounded by coffins. Usually, after the funeral the coffin disappears, into the ground or into the crematorium, but in the catacombs these very visible reminders of death were all around us, some of them still covered in velvet over a century after they’d first been deposited there.

Regular readers will remember that Flickering Lamps has visited Brompton Cemetery before, looking at the striking memorial to the First World War airman Reginald Warneford, VC. Many other recipients of the Victoria Cross rest at Brompton, as do a large number of other men who had distinguished military careers. Between 1854 and 1939, Brompton was designated as the District Military Cemetery for London, and during those years many servicemen were laid to rest there. According to the Friends of Brompton Cemetery, many of these men lie in unmarked graves.

The grave of General Alexander Anderson of the Royal Marines Light Infantry pictured above commemorates his military career. Some of the cannon balls have place names on them – Gaza, Beyrout – suggesting that Gen. Anderson served in the Middle East. The memorial is dwarfed by the mausolea that surround it, but it’s a simple, effective way of commemorating Gen. Anderson’s military service

There is also a section of the cemetery that is fenced off and specially reserved for military graves. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, there are over 300 military personnel from the two world wars buried at Brompton. Among these men are thirteen Victoria Cross recipients, including the pilot Reginand Warneford. The Chelsea Pensioners also have their own plot in the cemetery.

Other members of the armed forces are not buried at Brompton, but are commemorated on their relatives’ graves.

Many wealthy and powerful people are buried at Brompton – when the cemetery was first opened, plots were along the wide central avenue were sold “in perpetuity” to encourage wealthy individuals and families to build grand tombs and monuments.

The ornate and unusual memorial pictured above is the only tomb designed by the artist Edward Burne-Jones, who was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite and Arts and Crafts movements. This is the tomb of Frederick Richards Leyland, a wealthy shipowner and patron of the arts who died in 1892. Leyland had commissioned a number of works by Pre-Raphaelite artists, including Burne-Jones, who painted The Beguiling of Merlin. The beautiful chest tomb that Burne-Jones designed for Leyland is the only monument at Brompton to be Grade II* listed.

The most famous of the suffragettes is buried at Brompton. Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), died in 1928 and her grave is still visited by well-wishers today, who leave flowers and other trinkets. Her funeral was attended by many of her old WSPU colleagues and one newspaper described how “there were extraordinary scenes at the committal service at Brompton Cemetery. Hundreds of women pushed and jostled to get near the graveside.” (Dundee Courier, 19th June 1928) As a part of the movement that helped women to gain the right to vote, Emmeline was clearly a figure greatly admired by the many people who came to pay their last respects to her at Brompton. Her gravestone was created by the sculptor Julian Phelps Allen.

A significant figure in the public health of Victorian London is also buried at Brompton. John Snow was the man who discovered that cholera, which killed thousands of people in London during the 19th Century, was spread by water contaminated by raw sewage. Famously, he mapped cases of cholera in Soho, central London, as a way of pinpointing the water pumps that were responsible for spreading cholera – these maps clearly showed concentrations of cases in the areas immediately around affected water pumps. When Snow removed the handle of a pump he had identified as being a source of cholera, cases of the disease were reduced enormously. His work during the cholera outbreak of 1854 helped to pave the way for better sanitation in London.

Snow’s memorial was destroyed during the Second World War, when a bomb hit the cemetery, but a replica was provided by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland in the 1950s.

As well as being the resting place of many members of the armed forces, Brompton contains many graves of those associated with the arts, including the actor-manager Benjamin Webster, actor Brian Glover, artist Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale and Sir Henry Cole, founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum. It’s also thought that Beatrix Potter, who grew up close to Brompton, named some of her most famous characters after people named on monuments in the cemetery.

Brompton was closed to new burials in 1952, although since 1996 it has been possible to purchase plots for burial again. Around 200,000 people are buried at Brompton, and there are tens of thousands of monuments from the most elaborate mausolea to simple headstones.

The Friends of Brompton Cemetery run guided tours of the site on many Sunday afternoons, which is a great way to discover some of the cemetery’s many illustrious residents. There is also a cemetery open day held each summer, at which it’s possible to visit the cemetery’s catacombs and see exhibitions about the cemetery and its history. It’s a huge cemetery and it can seem difficult to know where to start looking – even after a number of visits, I still haven’t explored the whole place! Brompton is highly deserving of being described as one of London’s “magnificent” cemeteries, and as well as being home to one of the most impressive collections of tombs and monuments in the city, it’s also a peaceful place to walk and is clearly enjoyed by locals as a rare green space in a very built up part of London.

References and further reading

Cemetery History – The Friends of Brompton Cemetery http://www.signefied.talktalk.net/brompton/documents/FBC_history.html

‘Brompton Cemetery’, Survey of London: volume 41: Brompton F.H.W. Sheppard (ed), 1983 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=50028

£26.5million to restore UK’s cemeteries and parks, Big Lottery Fund, 8th January 2014 http://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/global-content/press-releases/uk-wide/080114_uk_pp_uk-cemeteries-and-parks

Reblogged this on First Night History.

LikeLike

Thanks – very informative and evocative. I wonder is there a term or collective noun for those of us who like to wander in cemeteries? Regards Thom.

LikeLike

There is – the term is ‘taphophile’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely post as always, but I’m amused that my favourite part is the squirrel on Henry Pettitt’s grave – life in the midst of death 😉 Also a great photograph of the monument to Dr Snow, which I last saw in person many years ago. Beautiful cemetery, may it long continue to be preserved!

LikeLike

I visited it last summer and it was full of wildflowers. I remember vivid pinks of the everlasting pea flowers. Some of the grass was left uncut as natural meadows. Lots of butterflies too.

LikeLike

I really love that these old cemeteries can be so full of life. Tower Hamlets is also particularly good for wildlife, especially butterflies.

LikeLiked by 1 person