Last summer, I visited a part of my native Lancashire that I’d never been to before – the Lune Valley. It’s a beautiful part of the world which probably gets overlooked due to its proximity to the famous, dramatic landscapes of the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales. The valley is probably most famous for Ruskin’s View, the stunning vista – immortalised by John Constable – that can be observed from Kirkby Lonsdale (just across the county border in Cumbria). But the Lune Valley also has a fascinating, half-forgotten history, and is home to some wonderful old churches.

This trip was one of the regular “adventures” that me and my Dad go on when I go back to Lancashire to visit my family. Dad was the first person to encourage my interest in history – when I was small, we visited lots of old houses, Roman ruins and other historic sites, and we still enjoy looking for interesting places to visit. On this occasion, we were drawn to the Lune Valley by the prospect of seeing kingfishers on the banks of the River Lune. In the end, we didn’t see any kingfishers, but we did come across rather a lot of history.

Between the junction of the M6 motorway and Kirby Lonsdale are several small villages. The first church we visited was a tiny little place, tucked away at the end of a lane. St John the Baptist, Arkholme, was for a long time a chapel of ease, only becoming a parish church in the 19th Century.

This little church dates from around 1450, although the fabric of the building was significantly altered in later centuries. The cross base pictured below is thought to be medieval.

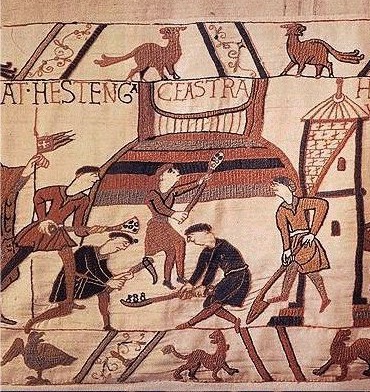

At the time, I didn’t realise what the strange, clearly man-made mound rising steeply behind the church was. My rather morbid imagination briefly wondered if it was some sort of pile of bones, centuries of charnel piled up and grassed over – although that seemed fanciful in such a tiny village. In reality, this mound is a Norman motte, built soon after the Conquest of 1066. Any traces of the bailey that would have surrounded it have been lost due to the development of the church and burial ground over the centuries, but in the early Norman period the motte would have been topped with a wooden castle and would have dominated the area.

![The motte behind St John the Baptist, Arkholme (image by [] via Wikimedia Commons)](https://flickeringlamps.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/geograph-1862341-by-karl-and-ali.jpg?w=663&h=497)

As well as the motte, which was topped with a keep, the bailey of the castle might have contained other buildings which would have been protected by defensive ditches. Many mottes have survived due to their substantial size – they can be found all over Britain – but unless more permanent stone structures were later built, baileys have often been lost after the castles fell out of use. The wooden keeps do not survive, but modern reconstructions can give an idea of what they might have looked like.

The church of St Michael the Archangel, Whittington-in-Lonsdale, is located on another Norman motte a few miles down the road from Arkholme. The square church tower dates from the early 16th Century, while the rest of the church building was extensively restored and remodelled in the 19th Century by the Lancaster-based architects Paley and Austin.

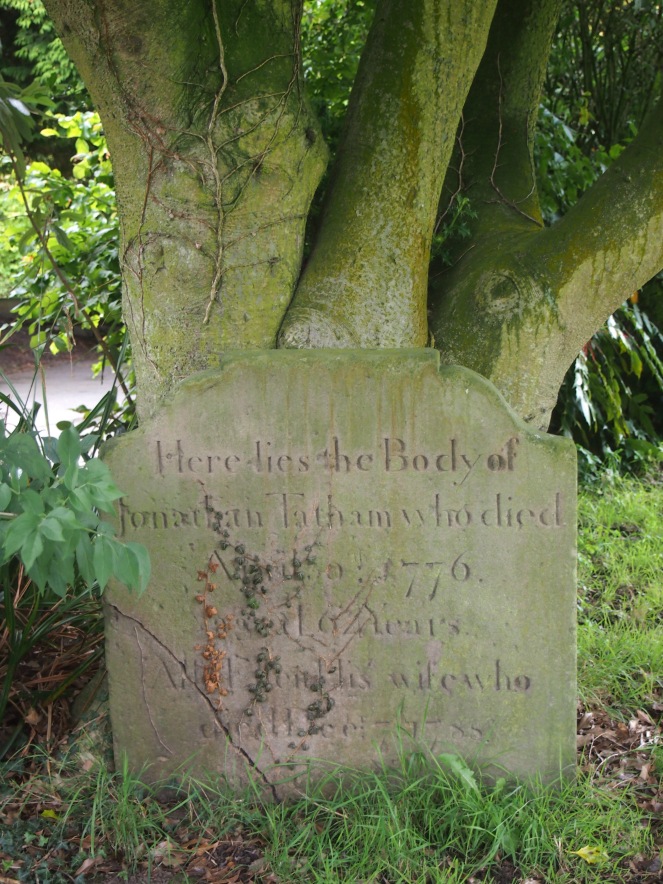

There are some interesting graves in the churchyard, the earliest one I found (attached to the wall of the church) dating from the 17th Century.

The steep sides of the motte must be challenging to maintain – when I visited, some graves could be seen peeking out of the long grass. Digging graves on such a steep slope must have been quite an arduous task for the church’s gravedigger.

It’s at this point that we ought to ask the question – why are there so many Norman fortifications in the Lune Valley? To look into this, we really need to consider the situation in the valley around the time of the Norman Conquest.

Before 1066, the local lord, whose considerable holdings centred on Whittington, was Earl Tostig, brother of King Harold Godwinson. Tostig was Earl of Northumbria and was in addition lord of a large part of northern England. He was not popular, and in 1065 he was deposed and exiled. He joined forces with Harald Hardrada of Norway, and both perished at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. King Harold Godwinson, of course, was killed at the Battle of Hastings a few weeks later and William of Normandy became King of England.

However, it took a long time before Norman rule was established over the whole of England, and in some areas the invaders encountered resistance. Infamously, William’s response to uprisings in the North of England in 1069-70 became known as the “Harrying of the North.” The Harrying has been described as William’s cruellest act – the campaign against the rebels and their Danish allies led to the deaths of thousands of people, and the destruction of crops, livestock and farmland led to a famine which cost even more lives.

In the Domesday Book of 1086, much of Amounderness (now the part of Lancashire north of the River Ribble), is described as “waste”. Arkholme and Whittington are described as being “King’s land” – but there isn’t a section in the Domesday book that describes the area that is now modern-day Cumbria. The map below shows the extent of William’s dominion by 1087, and Cumbria (labelled on the map as Cumberland and Westmorland) is not a part of this – making the settlements of the Lune Valley on the frontier of Norman England.

Armed with the knowledge of the Lune Valley’s status as a frontier in the Norman period, the concentration of motte and bailey castles makes much more sense. Other fortifications in the Lune Valley include motte and bailey castles at Hornby, Melling, Burton-in-Lonsdale and the next stop on our trip, Kirkby Lonsdale.

So far, we have visited two churches built close to Norman fortifications, but at last in Kirkby Lonsdale we have a church actually built by the Normans. The origins of the Grade I listed St Mary’s, Kirkby Lonsdale, are given away by the distinctive Romanesque doorway at the base of the tower.

The elaborate carvings around the Romanesque doorway have become quite worn over the years – when it was freshly carved, this doorway must have been quite spectacular.

Over the centuries, the church has been extended and parts of it rebuilt, but inside, some Norman arches still remain. Along with the motte and bailey castles, the stone churches that the Norman invaders build all over England were a prominent signifier of their power and dominance over the people of England. We’ve already seen this in an earlier Flickering Lamps post on Ely Cathedral, but as well as building imposing cathedrals the Normans also rebuilt a great many parish churches in stone as well.

The age of this mysterious stone sarcophagus, situated by the wall of the church, is unknown. The little green plaque next to it explains that it was “hewn by hand for a noble man.”

Visitors looking for Ruskin’s View have to walk through the churchyard of St Mary’s to reach the famous spot, and of course I couldn’t resist walking among the gravestones, looking at the designs and the inscriptions that mark the resting places of many of Kirkby Lonsdale’s people.

Another possible Norman motte, known locally as Cockpit Hill due to its later use as a cockfighting venue, is located close to both St Mary’s Church and Ruskin’s View. I didn’t get any pictures of the remaining earthworks, but this blog post contains photographs of the motte from various angles.

Spending a day exploring the Lune Valley was absolutely fascinating – as well as encountering some lovely churches and graveyards, the numerous Norman fortifications (which I’ve only really learned more about since starting to research this post) make the valley an unusual place. It’s hard to imagine what the valley must have been like when the motte and bailey castles were newly built – perhaps there were fewer trees, to give less cover to those opposing Norman rule. It’s a period of the valley’s history that – in common with many other places in northern England – has been lost, with only the records of the Domesday Book providing a brief insight into the settlements that existed at the time.

So if you’re passing through the Lune Valley, keep an eye out for the distinctive earthworks of the Norman mottes. They mark a forgotten frontier from a time when England was newly-invaded and still adjusing to the rule of the Normans. Ruskin’s View and the Devil’s Bridge might be the famous local landmarks, but if you look a little more closely, there’s a huge amount of history to be found.

References and further reading

Durham World Heritage Site – The Motte and Bailey Castle https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/architecture/castle/motte-and-bailey

The Lune Valley Motte and Bailey Castles, Matthew Emmott, Westmorland Gazette, 16th January 2006 http://www.thewestmorlandgazette.co.uk/news/673310.0/

Historic England – List entry summary for Castle Hill Motte, Arkholme http://list.historicengland.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1012695

‘The parish of Whittington’, in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 8, ed. William Farrer and J Brownbill (London, 1914), pp. 241-252 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol8/pp241-252

‘The parish of Lancaster (in Lonsdale hundred): Church, advowson and charities’, in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 8, ed. William Farrer and J Brownbill (London, 1914), pp. 22-33 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol8/pp22-33

Historic England – List entry summary for Cockpit Hill, Kirkby Lonsdale http://list.historicengland.org.uk/resultsingle.aspx?uid=1007153

What a lovely part of the country, my in laws live in Cheshire, so not far to go for a visit when we are on holiday, love learning about parts of the country that I haven’t visited and the Norman mottes are fascinating 🙂

LikeLike

It’s a really lovely part of the world, I’d definitely recommend visiting! Most of the churches we came across weren’t open for visitors to have a look inside, but nonetheless there was a lot of history to keep us occupied.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting, thank you. I hadn’t really appreciated that smaller mottes existed and survived like this; I think it explains some odd earth mounds I’ve seen over the years (although I’m not sure where, now).

LikeLike

Thank you! There must be so many mottes in various states dotted around the country – I think a lot of them are scheduled monuments now but they are easy to miss. I certainly didn’t immediately identify some of the mottes we came across.

LikeLike

Great post, and what a fascinating day you must have had! I love the motte beside the one at Arkholme, and especially the Norman church of St Mary’s.

LikeLike

The Norman church is really quite stunning. Although a lot of the Romanesque features have now been lost, the carvings around the tower doorway are stunning and there is a Green Man inside the church too (handily lit with a spotlight). We had a super day exploring the valley and it’s been really interesting researching the history of the area at the time of the Norman Conquest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful piece of history documented in your usual eloquent and elegant style. Very much enjoyed. I’m glad I did not die of Asiatic Cholera – sounds awful.

LikeLike

Thank you! Yes, that poor man who died at sea – what an awful end for him, but it’s lovely that the memorial commemorating him still survives.

LikeLike

Know all these churches but not the history of the fortifications!

LikeLike

It was really interesting learning about the fortifications – I wasn’t really aware of them on the day I actually visited the Lune Valley, but researching this post has been absolutely fascinating.

LikeLike

Spectacular! Thank you for sharing. I felt like I was right there! (I can dream :-)) ❤

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on texthistory and commented:

The Norman Frontier in Cumbria

LikeLike

Loved this. Have always loved driving through the Lune Valley on the way home to Scotland from trips down south. Was there last week, staying over at Lancaster. Shall have to linger longer the next time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Maggie! It’s such a lovely part of the world, isn’t it?

LikeLike

Isn’t it just? Very mysterious and it marks into moving into upland Britain. Many moons ago, when I was a student in London coming back to Glasgow on the train, the Lune Valley was my marker that I was heading home to Celtic Britain.

LikeLiked by 1 person