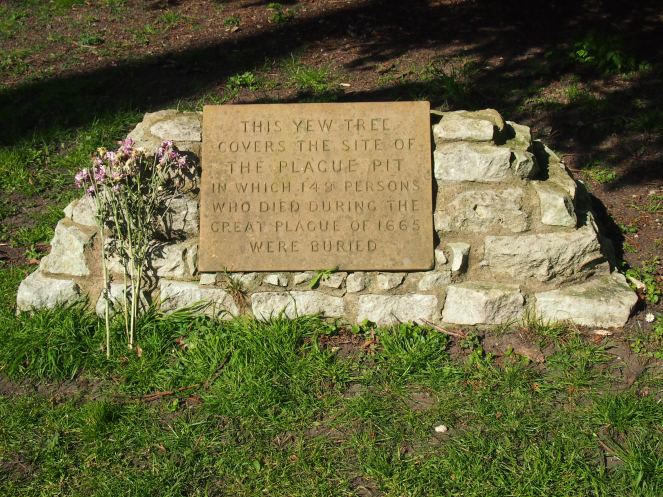

London’s many plague pits have a certain dark allure – they’re mysterious because so many of them lie unmarked, hidden and forgotten under the city’s streets, buildings and parks. We’ve seen pictures of archaeologists excavating long-lost mass graves uncovered on building sites, with huge jumbles of bones emerging from the soil and centuries-old eye sockets peering out at us. We’ve heard dark tales of homes built over old plague pits, haunted by restless spirits. But upstream of the old city, in a quiet suburb by the Thames, a plague pit lies in plain sight – marked by a yew tree and a little memorial. This is the plague pit at All Saints church, Isleworth, where local plague victims were laid to rest in a mass grave in 1665.

Accounts of the Great Plague of 1665 tend to focus on London itself. Cases of bubonic plague were first reported in the parish of St Giles in the Fields, outside the city walls, in the spring of 1665, and during the hot summer of that year the plague killed thousands upon thousands of Londoners – the worst outbreak of plague since the Black Death in the 14th Century. The diarist Samuel Pepys wrote about the large number of deaths in the city, and the exodus from London of those who could afford to leave. Official records state that around 68,000 people died of plague, but due to the chaos of so many people dying in a short period of time, plus the loss of some records in the Great Fire of 1666, it’s likely that the true death toll was even higher – perhaps around 100,000. In a city of around 600,000-700,000 people, this was a significant percentage of London’s population.

Churchyards quickly became choked with the dead and mass graves were dug in open spaces close to the city to cope with the number of people requiring burial. The picture below is one of the most well-known images of plague burials in 1665, showing large numbers of graves being dug in a field outside the city walls. Known sites of mass graves from the 1665 outbreak include Finsbury Fields to the north of the city walls, and Southwark, south of the Thames, and the “great pit” at St Botolph, Aldgate, in the east of the city.

London’s plague pits have been in the news in recent months – the Crossrail work taking place across the city has uncovered some of the huge mass graves that were dug to cope with the huge number of people dying during outbreaks of bubonic plague. Burials from the Black Death of the 1340s have been discovered near Farringdon, and a mass grave from the Great Plague of 1665 has been found close to Liverpool Street Station. Over the years, many suspected plague pits have been discovered by those digging the foundations of new buildings.

SKULLS UNDER A CITY OFFICE SITE (Gloucestershire Echo, 26th April 1924)

History is hidden by a hoarding in Farringdon-street, in the City of London. Builders’ men, working on a site where Farringdon and Stonecutter streets unite, have discovered what is believed to be one of the plague pits wherein London buried its dead in 1665. Thousands of bones, the remains of hurriedly buried human bodies, have been disinterred in foundation-digging. Men are digging all among bones. They come up by the shovelful. The soil is turned, and there are skulls, earth-stained, with their teeth still grinning. One straight-cut side of the foundation well is bristling with bones. They stick out like pegs from a wall.

The outbreak of 1665 brought to an end three centuries of intermittent outbreaks of bubonic plague in Britain. After the plague had subsided, many of the emergency plague pits were simply filled in and covered over, and some – typically those not sited on established burial grounds – were quickly forgotten. In Necropolis: London and its Dead, Catharine Arnold describes how some sites of plague burials, typically those requisitioned by authorities at short notice, quickly returned to their previous purposes. Other burial grounds were converted to new uses:

A piece of ground beyond Goswell Street, along the old lines of the City fortifications, where hundreds of victims from Clerkenwell and Aldersgate were buried, subsequently became a physic garden, one of the first examples of a London burial ground being turned into a park. Another piece of land at the end of Holloway Lane, in Shoreditch, became a yard for keeping hogs. (p.64)

In the 17th Century, Isleworth was a small riverside village in Middlesex, several miles upriver from London but undoubtedly there would have been a great deal of contact with the metropolis through trade along the Thames. Perhaps this is how the plague came to Isleworth. The loss of 149 people in a small community must have been devastating. These unfortunate parishioners were buried in a mass grave at All Saints in Isleworth, a church in a tranquil spot by the River Thames.

The plague pit at Isleworth was not forgotten. A yew tree was planted on the site of the mass grave, and burials continued in the surrounding churchyard until the mid-nineteenth century. I haven’t been able to find an exact date for the plague memorial, but the lack of references to it before the Second World War suggests that it may date from a similar time to the rebuilt church. When I visited, a bunch of flowers had been left at the memorial – the plague dead of Isleworth’s distant past are still being commemorated today. Quite a contrast to the forgotten pits that surround the City of London.

Why was a yew tree chosen to be planted on the site of the plague pit? Yew trees are a common sight in British burial grounds, with a lot of trees believed to be many centuries old. Some of these trees may be over 1,000 years old, much older than the churches built near them. One yew tree in a churchyard in Defynnog, Wales, is thought to be thousands of years old. The longevity of yew trees has led to the belief that these trees are immortal. At the same time, they are often associated with death – not just because they are often found in churchyards, but because their bright red berries and leaves are poisonous.

The various myths and beliefs around yew trees go back to pre-Christian times. Perhaps inspired by the unusual longevity of the yew, groves of the trees are thought to have been planted at holy places by Druids in pre-Roman Britain. As Christianity established itself in the British Isles in the Roman and Saxon periods, sites that had previously been associated with pagan worship became Christian sites – which is why there are many examples of yew trees being older than the churches built close to them.

Yew trees also had a practical use in the medieval period – yew wood was valued for the manufacture of good-quality bows due to its elasticity. Longbows were a vital element of medieval warfare and for that reason, yew wood was much in demand. Due to their poisonous nature, the safest place to cultivate yews was the parish churchyard, as it would have been fenced off and therefore inaccessible to livestock, which may otherwise have been poisoned by the toxic berries and leaves. Despite the large number of yews growing in churchyards, demand for the wood from these slow-growing trees outstripped the supply and various laws were passed to encourage the import of yew wood into Britain from mainland Europe. Today, compounds from the leaves of yew trees are used in the manufacturing of certain anti-cancer drugs.

All Saints is a strange-looking church – its 14th Century tower contrasts with the the modern church building. The previous incarnation of the church was lost to fire in 1943, not during an air raid but due to an arson attack. A temporary church was set up in the ruined nave until a replacement could be built – a new, permanent church building was completed in 1969.

The churchyard at All Saints is large – graves from the 18th Century onwards can be found on neatly manicured lawns or hidden amongst bracken and trees. Although parts of the burial ground are a bit overgrown, it doesn’t feel neglected, and it’s a pleasant, peaceful space containing a number of interesting old graves.

We’ll be visiting the churchyard at All Saints again soon, to look at another fascinating grave that warranted a blog post of its own.

References and further reading

Catharine Arnold, Necropolis: London and its Dead, Pocket Books, London, 2007

Heston and Isleworth, in A History of the County of Middlesex, Vol. 3, 1962 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol3/pp122-129

All Saints, Isleworth – Church History http://allsaints-isleworth.org/about-us/church-history/

Historic UK – The Reputed Plague Pits of London http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/LondonPlaguePits/

London Gardens Online – All Saints Churchyard, Isleworth http://www.londongardensonline.org.uk/gardens-online-record.asp?ID=HOU001

Vanessa Harding – Burial of the Plague Dead in Early Modern London http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/epiharding.html

The Great Plague of London, 1665 – Harvard University Open Collections Program http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/plague.html

The ancient, sacred, regenerative, death-defying yew tree, Daily Telegraph, 9th July 2014 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/countryside/10954261/The-ancient-sacred-regenerative-death-defying-yew-tree.html

Woodland Trust – Yew (Taxus baccata) https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/visiting-woods/trees-woods-and-wildlife/british-trees/native-trees/yew/

Ancient Yew Group http://www.ancient-yew.org/

Reblogged this on First Night History.

LikeLike

That was really interesting, I have been reading about the pits, due to seeing a program on the new railway, thank you 🙂

LikeLike

The Crossrail project has been so interesting from an archaeology point of view – so much has been discovered about London’s past. The pit at Isleworth is quite different to the big pits in the news, but I bet there are dozens of similar plague pits all over London – the difference with Isleworth is that it’s marked.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating article, from an always fascinating blog!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Fantastic history, Caroline, and I love those old yew trees as well. What an awful time, and it reminds us that we should feel very fortunate to live in the days of modern medicine!

LikeLike

We are so lucky today – although there are still so many horrible illnesses around I am glad that epidemics like the plague are few and far between now. It is hard to imagine such a large proportion of a place’s population dying so quickly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, very interesting history and beautiful photographs too. We just don’t have anything like plague pits in the US. Thanks for all the great information about yews as well.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Great work, Caroline.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Fascinating article regarding the burial pits, which I had never heard about. Although I know London is rich in historical events, and I know its true of all of Europe. Thank you so much for an intriguing look into the past.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Fascinating as ever, I lived in Twickenham and passed that church every day, not knowing the history, I shall make a point of going inside now.

Thank you

LikeLike

Thank you for the info on All Saints Isleworth. very interesting and would love to discuss…

LikeLike