St George’s Gardens, the park on the site of the former churchyard of St George in the East in Stepney, is a neat, peaceful place – when I visited, the play area was full of children, and other people were relaxing on benches or looking at the old monuments near the church. In the midst of all of this is a derelict building that looks terribly sad and out of place. However, this forlorn little building has a fascinating history that includes that most infamous of East End criminals, Jack the Ripper, and later became a pioneering centre for the education of local children.

Built in about 1876 in the old churchyard of St George in the East (which had by the 1870s been closed to new burials for many years), this building started life as a mortuary. Although many years of disuse have left the building in a sorry state, the attractive patterned tiles used in the building’s construction can still be seen – designs that mirror the gateposts at the entrances to St George’s Gardens on Cable Street.

At the time that the mortuary was completed, such buildings were still a rare sight in London. This was despite Edwin Chadwick recommending the building of more mortuaries in 1843, when he published a supplement to The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population looking specifically how the poor of London dealt with the death of family members.

Chadwick found that many of London’s poorer familes, many of whom lived in just a single room, would keep the body of their deceased family member at home until the time came for a funeral and burial. As it sometimes took time for families to get the required money together to bury their loved one, a body could remain in the family’s living space for two or three weeks, perhaps even longer – clearly a health hazard as the body would be decaying. Like most of his contemporaries, Chadwick believed in the miasma theory – that putrid smells and vapours caused fatal diseases – and as a result of his findings in his 1843 report, he recommended that mortuaries were built to house the dead until their burial.

However, the idea of sending the body of a deceased family member to a mortuary was slow to take hold. The parish of St Anne, Soho, was the first to provide a mortuary, in 1854, but for the most part mortuaries tended to be attached to institutions such as workhouses and hospitals.

Families had many reasons for wishing to keep the body of a loved one at home until the funeral. The fear of bodysnatching was still a very real one in the 19th Century, as was the fear of being buried alive. Keeping a body at home would allow the family not only to keep an eye on it, but also to ensure that the person had died (as it was not always easy to tell the difference between a coma and death and this time, until decomposition began). People were also afraid that an unattended corpse might be dissected without authorisation In addition to these fears, it was also a tradition to keep the body at home – that way, friends, relatives and neighbours could come to pay their respects to the deceased and provide support to the bereaved family.

The slow growth in use of mortuaries in the later 19th Century was partly influenced by legal matters. Coroners had often held inquests in private homes or local taverns – the idea of a corpse being laid out in a pub for all to see is quite an unbelievable thing to us nowadays. Amid concerns about the suitability of these makeshift inquest venues, coroners put pressure on London’s vestries (predecessors of the Borough Councils) to provide suitable locations for both post-mortems and inquests, and gradually mortuaries became more common across the city. Changing people’s perceptions of where a body should lie after death was, however, a slow process, and many mortuaries were at first little used.

St George in the East, a stunning Baroque church built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in the 1720s, was situated in an area where poverty and overcrowding were rife. When the church was first opened, the area to the east of the City of London was still fairly rural, but as the East End grew and grew, the parish of St George in the East became crowded with those displaced by slum clearances in other parts of London who flocked to the area for its cheap housing.

Probably the most well-known person to rest in the mortuary at St George in the East was one of the suspected victims of the infamous Jack the Ripper. Elizabeth Stride was the first of two women to be brutally murdered in the same evening at the end of September 1888. Elizabeth was found with her throat cut around an hour before a second victim, Catherine Eddowes, was found nearby, with her throat also cut and her body mutilated. Elizabeth Stride’s body was taken to the mortuary at St George in the East, where a post-mortem took place, and she was buried in a humble grave in the City of London cemetery on 6th October 1888.

The mortuary at St George in the East closed in about 1900, as by that time technology had advanced enough for bodies to be refrigerated to delay decomposition – a facility which the little mortuary at St George in the East wasn’t able to provide.

The former mortuary was not out of use for long. A donation of £253 from an anonymous benefactor enabled the building to reopen as the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney Nature Study Museum in about 1904. The museum was the brainchild of Kate Marion Hall, curator of the Stepney Borough Museum, and Claude Hinscliffe, curate of the parish of St George in the East. Claude Hinscliffe was the first secretary of the School Nature Study Union, which was set up in 1902/3 and was influential in the provision of nature study in London in the early 20th Century. Stepney was the first London borough to use ratepayers’ money to provide museums for the education of local people.

The Nature Study movement was a nationwide phenomenon in the early years of the 20th Century – whilst researching this post, I’ve found reports of Nature Study centres, exhibitions and school visits in places all over Britain, including Exeter, the West Riding of Yorkshire, and Dunfermline. The movement also enjoyed popularity across the Atlantic in the United States. There were concerns that children growing up in crowded inner-city areas never got to experience the wonders of nature at first hand that rural children could enjoy.

Stepney’s Nature Study Museum was a huge success. During the school summer holidays, up to 1,000 visitors came through its doors each day, and the little building was sometimes packed with 70 children or more at one time. As well as attracting local schoolchildren during the holidays, the museum was part of the local school curriculum and played host to school visits.

![Children viewing specimens at the Nature Study Museum (image from [])](https://flickeringlamps.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/naturestudy.jpg?w=420&h=641)

In recent years, keeping bees has become more popular in built-up parts of London, with hives often being set up on roof gardens and terraces. But “urban honey” is nothing new – the bees at the Nature Study Museum were clearly a big attraction, if this little piece from a newspaper in 1927 is anything to go by:

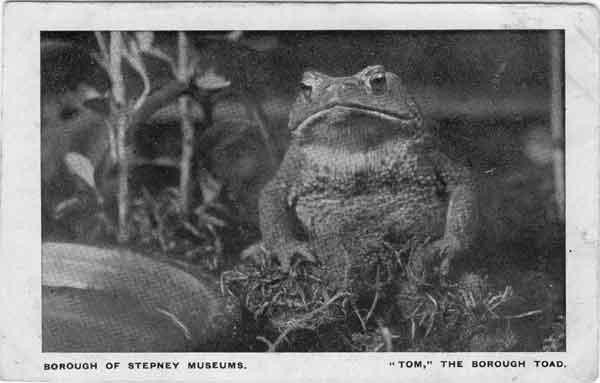

Many other live animals lived at the museum. Most – like Tom the toad, pictured below – were aquatic creatures. Anemones, fish and amphibians were all kept in tanks, and outside was an “ant-hive” and an aviary. Other creatures were more difficult to take care of. A troublesome monkey – perhaps one of the exotic creatures donated by the museum by a sailor stopping at London’s docks – was known to bite museum staff and visitors.

The Nature Study Museum closed its doors following the outbreak of the Second World War. Many local children had been evacuated to rural areas and the museum’s contents were relocated to the Whitechapel Museum. In April 1941, devastating fires caused by a landmine gutted the church of St George in the East and many of the surrounding buildings. The museum escaped the flames, but it was never to reopen, even after a new church was constructed within the restored shell of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s building in the 1960s.

The Nature Study Museum may be long abandoned and decaying, but nature is very much evident in St George’s Gardens. The grass was cloaked with daisies, and various trees and flowers were reclaiming the old mortuary for nature.

Best of all, though, was what I spotted high on the church’s striking tower. A high-pitched call drew my eyes skywards, and there it was – a peregrine falcon, observing everything around it from its superb vantage point. These beautiful falcons are known to nest on tall buildings in cities – sites that mimic their more usual habitat of steep cliffs.

It’s a crying shame to see a small but fascinating piece of London’s history crumbling away. Not only does the building’s original use as a mortuary provide an insight into attitudes towards death amongst London’s families (and also plays a small part in the Jack the Ripper saga), but the Stepney Nature Study Museum is a wonderful early example of natural history teaching in an inner-city area. In recent years there have been a number of attempts to restore the old museum and make good use of the building again, but to date none of these schemes have come to fruition. Let’s hope that one day soon, this sad little building may be able to retake its place in the local community.

References and further reading

St George in the East – History http://www.stgite.org.uk/history.html

St George in the East – Nature Study Union http://www.stgite.org.uk/naturesstudy.html

Derelict London – Cemeteries, Churches and Chapels http://www.derelictlondon.com/cemetery–churches.html

Pam Fisher – Houses for the dead: the provision of mortuaries in London 1843-1889, The London Journal, Vol. 34, No.1, March 2009 (source – PDF)

Caroline Sandes – The Mortuary that became a museum, Institute of Historic Building Conservation, Newsletter Winter 2011 http://www.academia.edu/6003360/The_Mortuary_that_became_a_Museum_-_St_George_in_the_East_London

Field Studies Council – A Review of Research on Outdoor Learning, March 2004 https://www.field-studies-council.org/media/268859/2004_a_review_of_research_on_outdoor_learning.pdf (PDF)

A lovely piece of local history. I love the faded ‘Nature Study Museum’ lettering above the door.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

A really good piece. I haven’t been to St George in the East for years, I visited in the 1980s when I was doing an undergraduate dissertation on seasonal unemployment in the parish in the 1860s. While the records were at the old County Hall I wanted to get a feel of the parish and was amazed by the exterior of the church, but vaguely remember the mortuary which seems to have deteriorated a lot.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s a real shame to see the mortuary/museum in such a poor state, especially since the rest of the church and park are so well kept. Hopefully one of the schemes to renovate it that seem to pop up every few years will actually come to fruition.

LikeLike

Very interesting read. London Docks was, of course, just the other side of the road and the beautiful Hawksmoor church received a direct hit during the Blitz- the centre was destroyed, but the wonderful exterior survived; inside has been restored and I love it because it shows what could be achieved at modest cost- it’s inviting and very special. Incidentally, the immediate surrounds were the sites of Lady Huffham’s infamous brothels in Charles Dickens’s last novel, The Mystery Of Edwin Drood

LikeLike

Thank you! I wasn’t aware of the Edwin Drood connection to St George’s. It’s a shame that so many of the old buildings in the area have been lost, but you are right, a good job was done to preserve the exterior of the church and I think it still looks quite magnificent today.

LikeLike

Another most interesting piece! Slightly off-topic, but I seem to recall that the suspected Ratcliffe Highway Murder was buried in the church, alongside some of his victims …

LikeLike

Thank you!

You’re right about some of the victims of the Ratcliffe Highway murders, but I’ve not heard anything about a suspect being buried at St George. As they never fully solved the murders, who knows?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Linden Chronicles: The Wolf's Moon by Patrick Jones and commented:

Excellent pictures and history from Flickering Lamps!

LikeLike

Fascinating and informative post, thank you. Appreciate the juxtaposition of old and new, and the peregrine falcon makes the perfect ending.

LikeLike

Thank you! Spotting the falcon was the icing on the cake.

LikeLike

All London Boroughs should have a Borough Toad. I had an archive mouse once but it disappeared…..

LikeLike

I hope the archive mouse didn’t cause bits of your archive to disappear too!

LikeLike

Love the Borough Toad every council should have one!! I visited the church and former mortuary last year it is such a shame the building isn’t used at all now…your photos are great too and very similar shots to the ones I took. Lucky you spotting the peregrine falcon!

LikeLike

It was a real treat to spot the falcon! There are quite a few of them in London but it’s always nice to see one.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this post! It looks like an intriguing little park; shame about the museum. Judging by the pictures, it looked a bit like the Booth Museum in Brighton.

LikeLike

It’s a real shame the museum has fallen into such disrepair, it looks as though it was a great place for local kids before the war.

LikeLike

A sad fate for such a sweet little building with so much history. And so close to a beautiful Hawksmoor church too 😦 I hope someone manages to restore it before it goes altogether!

LikeLike

Great post Caroline, it got me thining yesterday, the image of the Skull and bones? I have come across quite a few of these in Ireland, not just on graves but also Castles, churches and cathedrals. Whilst they are normally passed of as Momento Mori, I was recenlty enlightened as to an alternative meeting. The Skull and bones symbols were also used by the Templars!

LikeLike

I wasn’t aware of the link between the skull and crossbones and the Knights Templar! I suspect that most usage of the symbol is intended to represent memento mori, but it’s quite possible that organisations used it as one of their symbols too (the SS is a famous example). A quick search showed that it’s sometimes linked with the Freemasons too, which might explain the link with the Templars.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I always believed that it might be connected to masonic orders, until I came accross the templar connection.

LikeLike

Thank you for such a fascinating and well-researched post. I followed a Google trail here whilst trying to pin point a piece of research for the Victorian era mystery I’m writing, and I came away with so much more. Greatly appreciated! 🙂

LikeLike

Another great article. I read that delaying burials esp in summer led to bodies putrefying so they added taps to drain off the liquid. Ghastly stuff! Officials sometimes claimed the poor refused to bury the dead – didn’t want them to go. It was about money of course.

LikeLike

Really interesting article, thanks for this Caroline. I’m reading a book by Geoffrey Fletcher called Down Among the Meths Men and in it he describes the crypts beneath St George in the East. Did you uncover much about these during your research and do you know whether they are still accessible by any chance?

Thanks again

LikeLike

Hi Toby, I believe the crypt was remodelled after the Blitz damage and is now used as a hall space, so it might be worth getting in touch with the church to see if it’s possible to visit.

LikeLike

Shocking to find later that this old building had some dark history behind these walls of this old abandoned building. Played in this place as a kid in the 70s with my mates in Solander gardens flats.

It had parka flooring and marble worktops to stand the cabinets on. Some of the cabinets had rare unusual looking fish and birds. Down n outs used to go in there to keep warm. But was also used for the park keeper to store petrol Lawnmowers..as there was a lot of down n outs around this area n soup kitchen off cable street used to use the park a lot mind as kids we were reckless too.. used see a lot of Surgical Sprit bottles around the park and bottles of there favourite tipple. There was a old bombed debris at the side of the church many fires there too, but down n outs set the place on fire.

LikeLike