Oak trees loom large in English history. From the sacred oak groves of pre-Roman Britons and the oak wands used by Druids to the oak tree that sheltered the future King Charles II as he escaped from the forces of Oliver Cromwell and the countless oaks used to construct England’s proud navies and merchant ships, this tree – perhaps more than any other – is seen as the national tree of England. Many individual oaks up and down the country are revered and protected for their age, their size and shape or the stories attached to them. The oak we’re looking at today is famous not just for its huge size and distinctive shape, but also for its link to that most famous of English legends, Robin Hood.

The Major Oak is one of many ancient oak trees that can be found in Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire. Today, only remnants of the forest remain, but in the past Sherwood Forest covered a huge area of Nottinghamshire and surrounding counties. For centuries it was a huge royal hunting forest, but over the centuries large parts of the forest have been lost to deforestation and storms and today the Major Oak and other nearby ancient oaks are clustered in a relatively small part of the old forest that remains near the village of Edwinstowe.

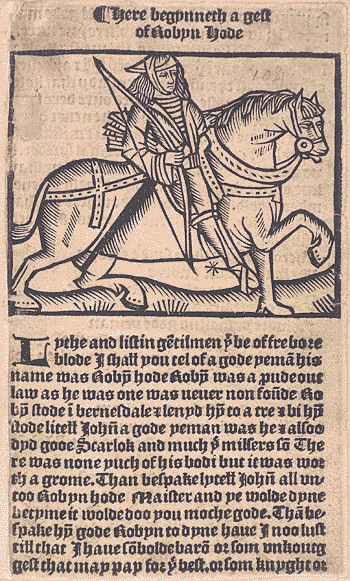

Sherwood Forest, of course, is synonymous with the exploits of the legendary outlaw Robin Hood and his Merrie Men. A skilled archer, Robin Hood was based in Sherwood Forest and robbed the rich, giving the money he stole to the poor. His arch-enemy was the villainous Sheriff of Nottingham, and Robin features as the hero of many medieval ballads. Probably due to its distinctive and impressive appearance, the Major Oak has became part of the Robin Hood legend – it is claimed that Robin and his Merry Men used the hollow trunk of the tree as a hideout.

It’s not clear when the Major Oak first became associated with Robin Hood, but – leaving aside the arguments about whether or not Robin Hood actually existed – the tree would not have looked like it does today in the 12th or 13th Centuries (the time that the Robin Hood stories are usually set). It’s estimated that the tree is about 800-1,000 years old, so during the reigns of Richard the Lionheart and King John it may only have been a sapling, or perhaps a young oak in its prime – not the hollow, gnarled tree we see today. But, more than likely, there would have been other ancient oaks in the forest in Robin Hood’s time that would have been excellent hiding places for those on the run from the law.

The oak gained its name from Major Hayman Rooke, a local antiquarian and archaeologist who in 1790 published Remarkable Oaks in the Park at Welbeck, describing many of the old oaks in Sherwood Forest, including the venerable tree that would later be named after him. Before the publication of Rooke’s book, the Major Oak was known as the Cockpen-tree, as birds bred for the blood sport of cockfighting were kept in the tree’s hollow trunk by a local man.

Rooke was impressed by the oak’s appearance and suspected it to be of a great age.

I think no one can behold this majestic ruin without pronouncing it to be of very remote antiquity; and might venture to say, that it cannot be much less than a thousand years old.

Rooke also playfully remarked that “the inside [of the tree] is decayed and hollowed out by age, which, with the assistance of the axe, might be made wide enough to admit a carriage through it.” It seems unthinkable to do such a thing to a venerable old tree like the Major Oak today, but in the 18th Century another tree in Sherwood Forest, the Greendale Oak, was so large that that Duke of Portland made a bet that he could drive a horse and carriage through a hole cut in its trunk. This hole was duly made and the Duke won his bet. The poor Greendale Oak didn’t fare so well, though – the image below shows a sad remnant of a once-mighty tree.

Ancient oaks are often hollow – a fungus attacks the core of the tree, causing the wood to rot away, but the tree does not die and unless felled by the wind, an oak can live for centuries with a hollow trunk. This is because the fungus that causes the decay does not attack the newer growth rings on the outside of the trunk.

There are various theories as to why the Major Oak has such a broad trunk – it is possible that it is in fact two or more trees fused together. Another theory is that at some point during its life the tree was pollarded – a form of pruning where branches are removed to encourage the growth of straight boughs, or (commonly in the medieval period) to provide leafy fodder for animals. However, there’s not much evidence that the oaks in the part of Sherwood Forest where the Major Oak resides were ever pollarded.

The gnarled, twisted appearance of the oak’s branches is common in older oak trees – the irregular way that the leaf buds are arranged on twigs and branches means that the tree’s growth tends not to be straight and regular. The huge canopies of mature oak trees provide plenty of shelter, and in many parts of Britain it was at one time common for preachers to speak to crowds beneath oak trees – the origin of the term “Gospel Oak”.

The strength and versatility of oak wood has always been prized, and the growth of oak trees was often manipulated in order to produce wood suitable for certain enterprises, such as shipbuilding. Many oaks were felled from the 17th Century onwards for the building of warships – the use of oak as the primary material for these ships led to the adoption of the song “Heart of Oak” by the Royal Navy as its official quick march.

Attempts at preserving the Major Oak have been well-meaning but have often caused more harm than good to the old tree. In the early 20th Century, metal chains and bands were attached to the tree’s branches in an attempt to support them, but the tree soon grew around them. Parts of the trunk and branches were later clad in lead, leading one person visiting for the first time as a child to describe the tree as looking “like it had come from another planet as it was encased in grey metal cladding with the tired old branches resting on sticks.” (source)

Thankfully, today the tree is more appropriately cared for. It has been fenced off for many years as having thousands of visitors trampling the soil around the tree’s roots were causing the tree to become damaged. The strange metal cladding has also been removed, and the oak’s branches are now supported by metal poles.

It’s no surprise that ancient oak trees, with their hollow trunks and distinctive, twisted branches have found their way into many stories and myths. The Major Oak isn’t the only tree in Sherwood Forest to have links with Robin Hood. The Shambles Oak, now no longer standing, was also known as Robin Hood’s Larder, and the story went that the tree’s hollow was large enough to accommodate hooks for hanging poached venison out of sight of the sheriff and his men.

The Major Oak was voted as England’s “Tree of the Year” in 2014, with many of its rivals also being oak trees (including the fantastically-named “Old Knobbley” in Essex). It’s a popular tourist attraction – although this has proved over the years to be a mixed blessing, culminating in the tree being fenced off. But even if visitors can’t get up close, the tree still has an imposing presence. It’s still a popular spot for marriage proposals. Long may it continue to inspire and enthrall visitors from all over the world.

References and further reading

Greak Oaks of Sherwood – Nottingham’s Hidden History Team, 10th April 2015 https://nottinghamhiddenhistoryteam.wordpress.com/2015/04/10/great-oaks-of-sherwood/

Major Hayman Rooke – Remarkable Oaks in the park at Welbeck, 1790 (accessed at http://www.eyemead.com/RO-TEXT.htm)

Roger A Redfearn – The Greatest Giants of Sherwood, Country Life, 17th January 1974 (acccessed at http://www.eyemead.com/sherwood.htm)

Nottingham’s Major Oak voted England’s Tree of the Year, The Guardian, 14th November 2014 http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/nov/14/nottinghams-major-oak-voted-englands-tree-of-the-year

Meeting with a remarkable tree – the Major Oak, Long Eaton Natural History Society, 18th September 2014 https://lensweb.wordpress.com/2014/09/18/meeting-with-a-remarkable-tree-the-major-oak/

Simon Schama – The tree that shaped Britain, BBC News Magazine, 7th May 2010 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/8668587.stm

Oak trees – and their part in our history, Big Issue, 24th October 2013 http://www.bigissue.com/features/3159/oak-trees-and-their-part-our-history

Interesting post, although going somewhere as a tourist and then suggesting that two linked pillars of its tourist industry – Robin Hood, and said person hiding in a large tree – may be myths, is a little harsh. Seiously though, the Major Oak hasn’t aged that well over the last few decades – the props and the fencing off weren’t there when I was a child growing up in Mansfield, which is a few miles away. I remember both going inside and attempting to climb it, not very successfully mind.

LikeLike

Oh, I definitely think the Robin Hood stories have some basis in fact! Besides, there were probably some ancient oaks in Sherwood in the 12thC, now long gone, that would probably have made for similarly good hideouts. The tree itself is just wonderful and it was great to finally get to visit it.

I would have loved to have climbed (or attempted to climb) the tree as a child, although I can definitely see why they keep people at a distance now. The 20th Century wasn’t kind to a lot of the ancient trees in Sherwood (didn’t some of them get set on fire?)

LikeLike

Almost certainly, there is quite a lot of woodland around there, little of it ancient though, mainly Forestry Commission regimented pines, and a fair number of ne’er do wells. I remember my Dad mentioning quite a big fire around Edwinstowe a few years ago.

LikeLike

I had a copy of Robin Hood as a child. I think the book had been in the family for years. I loved it, especially the illustrations. Then it was on TV with Richard Greene as Robin. I remember the music well. Now I have oak trees in my garden. Not 800 years old but certainly mature. I love looking up at them and wondering what has happened around them over the years. The oak is part of our history and let big may it remain so.

LikeLike

I too grew up with books, films & TV shows about Robin Hood – it was great to finally get to visit Sherwood Forest! I feel quite humbled by the ancient oaks – they are so old, so magnificent & they’ve seen so much history over their long lives. Wonderful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an interesting post! I had no idea that oaks could be so old or grow so large and gnarly! The oldest one I’ve seen was about 400 years old and was nowhere near as impressive. I like your choices of both photos and art – they enhance the piece beautifully.

LikeLike

Thank you! I have seen ancient oaks before but none so huge or impressive as the Major Oak. Quite a remarkable tree. I really enjoyed taking pictures of it so I’m glad you enjoyed the photos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic post, Caroline – thank you! Fascinating descriptions and great photos. I’d love to see this magnificent old tree for myself. What awful things we’ve subjected venerable old trees to, over the centuries – but I hope this one stands firm for many years to come.

LikeLike

Thank you! It makes me sad to think about what happened to the the poor old tree that had a carriageway driven through it for a Duke’s bet, but I’m really glad that the Major Oak has survived and is now being cared for. The tree itself is a great spectacle and I’m so glad I’ve been able to visit it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Somehow I never got around to spending much wandering-time in Sherwood – Epping always seemed to take precedence as our go-to, and I certainly spent wander-time in the New Forest and the Forest of Dean, but Sherwood not so much. I think it was the Robin Hood nonsense that put me off 😛 Lovely post though!

LikeLike

As a child I visited the Major Oak and remember climbing inside it. It was quite a scary thing for a small child. The opening was narrow and the inside dark, with a distinctive (though not unpleasant) smell of rotting wood. In those days it had no props under the branches but there were chains supporting a couple of branches from above. I was super-impressed that it was ‘Robin Hood’s tree’, of course.

LikeLike