[Content note: this article contains multiple images of human remains] The church of St Leonard sits on a hillside in the pretty coastal town of Hythe in Kent, overlooking the English Channel. Its history goes back at least 900 years, perhaps even further – a lot of the churches in the area have pre-Norman origins. It’s a beautiful and imposing building – but if you visit the church’s crypt you will find yourself coming face to face with some unexpected people.

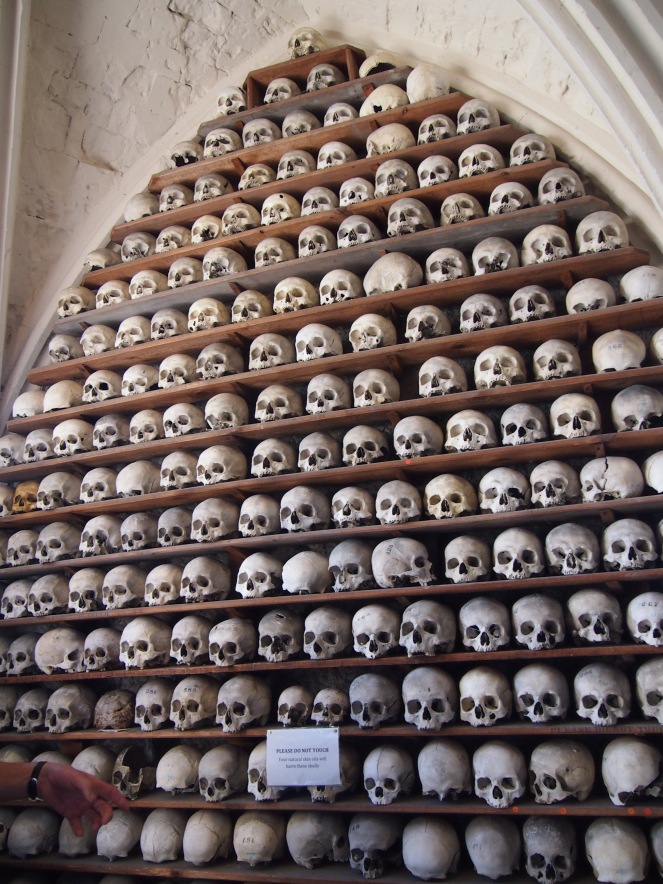

The crypt is home to an ossuary – a house of bones. Hundreds of human skulls peer out at the visitor from carefully-stacked shelves, and much of the crypt is taken up by a vast pile of bones, dotted here and there with grinning skulls.

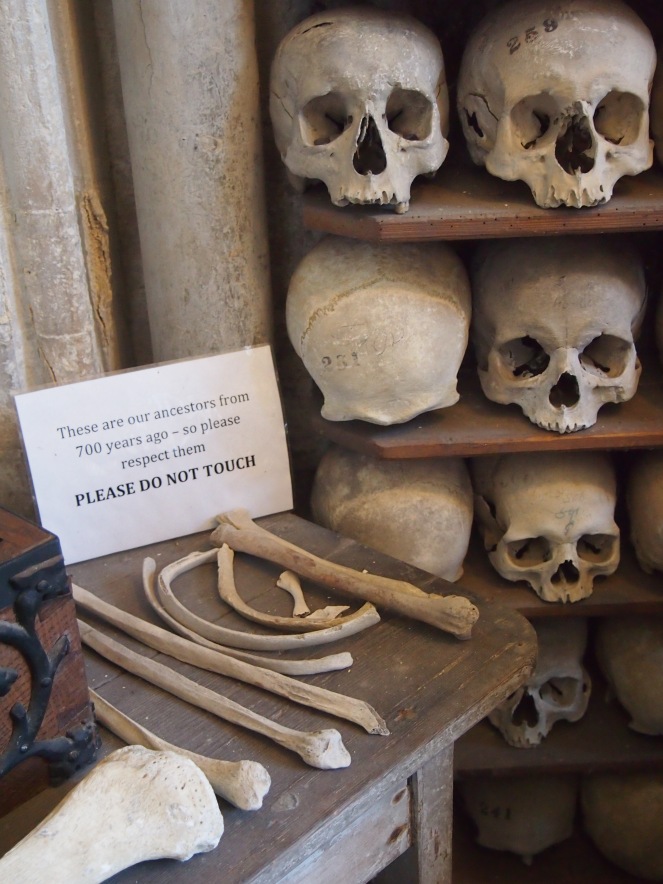

These are old bones. It’s thought that many of them were exhumed from the churchyard when the church was extended in the 13th Century. Others came from churchyards in the area that belonged to churches that were closed and demolished during the medieval period – when the land was sold, those buried in the churchyards were exhumed. All of the bones are at least 700 years old – some may be much, much older. It’s quite possible that some of Hythe’s Roman residents are staring out at us from the shelves of the crypt.

These bones were not removed to the building they reside in today. Instead, they were taken to a charnel house which stood in the churchyard. Charnel houses were widespread in English churchyards in the medieval period. They were designed to house bones that were disturbed when new graves were dug. Cremation was not accepted by the church as a method of disposing of the dead in this period – it was believed that some physical remains needed to survive in order for people to be resurrected at the End of Days. Skulls and thigh bones are the most robust bones in the human skeleton, and the most likely bones to survive a long time, and therefore (perhaps rather pragmatically) these were often the bones retained when a grave was exhumed.

Charnel houses are still used in some countries, but they fell out of use in England after the Protestant Reformation of the 16th Century – generally they were demolished and their contents dispersed or reburied (the contents of the charnel house at St Pauls’ Cathedral, for example, were taken to the open space of Bunhill (or Bone Hill) Fields north of the City of London). But, for some reason, the bones at St Leonard’s were retained. Perhaps they were a local curiosity that was too lucrative to the church to consider disposing of. The first written accounts of the bones appear in the late 17th Century, describing “an orderly pile of dead men’s bones” in the crypt – clearly by this time, the original charnel house had been demolished and the bones relocated. It’s not much more than a hundred years since the skulls were arranged onto shelves and the huge stack of bones was constructed.

People have long speculated about the origin of the bones at St Leonard’s. It’s been suggested that they might have been victims of a battle, perhaps even the Battle of Hastings, or victims of the mass mortality during the Black Death. But these particular speculations are very unlikely – only a tiny handful of the skulls show signs of violent injury, and plague victims tended to be buried in quicklime, which hastened decomposition.

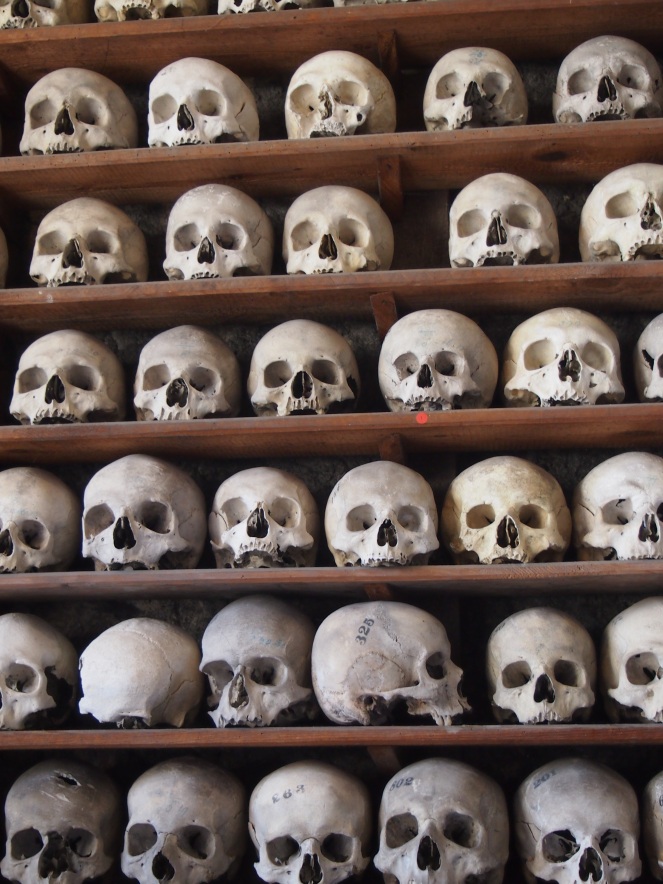

The true identity of the people in the ossuary is less dramatic, but certainly no less interesting. These bones are of the ordinary residents of Hythe, the people who lived, worked and died in the town. Unsurprisingly, the bones have been analysed by specialists on a number of occasions and it’s thought that just over half of the skulls are of females. Almost all of the bones present are from adults – children’s bones are more fragile and less likely to survive a long time, although there are a couple of small children’s skulls in the collection. For many years it was thought that the skulls were from dwarves, but analysis of the skulls’ teeth indicated that they belonged to children aged between about four and six years old.

Analysis of the bones has uncovered many interesting things about the people living in medieval Hythe. The eye sockets of nearly a quarter of the skulls have cribra orbitalia, a “pinpricked” effect which indicates that those individuals suffered from a chronic iron deficiency, or even possibly malaria. Hythe is close to Romney Marsh, and the damp, marshy landscape provided an ideal breeding ground for the mosquitoes that spread the disease – malaria was only eradicated in the area when large areas of marsh were drained for farming.

The teeth present in the crypt have also provided fascinating insights into the lives of the people they belong to. It has been noted that there is an almost complete lack of any dental cavities, suggesting that the diet of local people was low in sugar, although the worn state of many molars shows that the gritty flour used to make bread gradually eroded people’s teeth.

Some of the skulls show sign of more unusual health problems. One skull (which I don’t seem to have got a picture of) had larger than normal eye sockets, an indicator of Graves Disease, a disease that affects the thyroid gland and causes it to become overactive, resulting in a swelling on the neck and bulging eyes. The lump on the skull pictured below is a benign tumour. The inside of the skull was unaffected by the tumour, and today such a growth would be relatively simple to remove under anaesthesia.

The bones at St Leonard’s are displayed in line with the Church of England guidelines on the display and treatment of human remains.

Displays of human remains in museums are popular with the public and are acceptable provided that they serve a clear educational purpose. […] They may also be of value to illustrate aspects of local history and archaeology. […] When displayed at ancient monuments or historic sites, human remains should aid public understanding of the site. Displays of human remains should always be accompanied by sufficient explanatory material. Display conditions, like storage conditions, should ensure the physical integrity of the remains. (source)

There is undoubtedly something rather ghoulishly thrilling about coming face to face with the skulls of people who lived hundreds of years ago, but the ossuary at St Leonard’s isn’t there to satisfy our morbid curiosity. The bones can teach us so much. A volunteer is always on hand to discuss the historical value of the remains, to recount stories about individual skulls or bones, and to ensure that the bones are not damaged or disrespected in any way. There are clear signs asking visitors not to touch the bones (which could damage them) and to be respectful of the people whose mortal remains reside in the ossuary. One display includes prayers that can be said for the living and the dead.

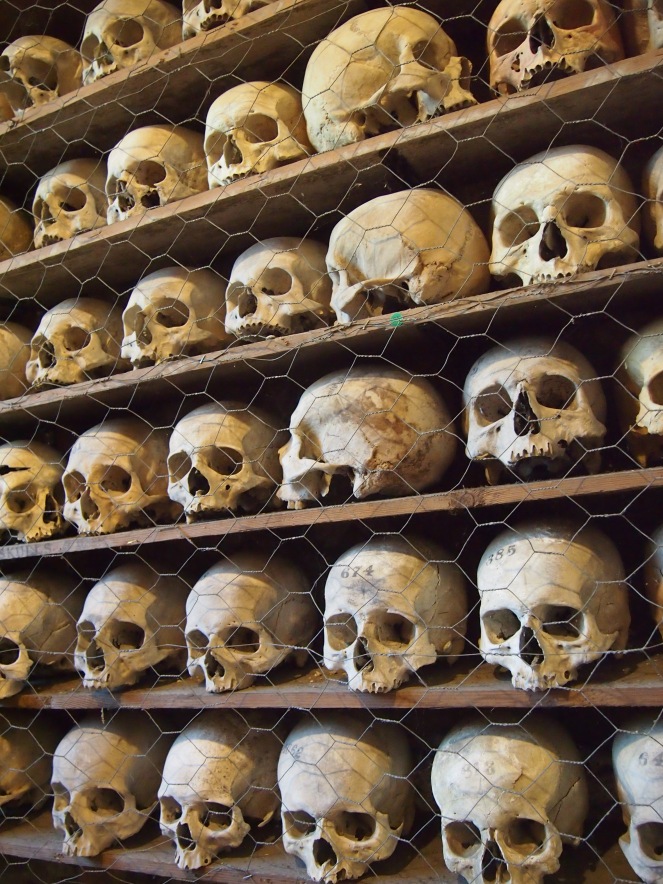

On one of the shelved alcoves, a yellowish skull stands out from its bleached white neighbours. This skull was stolen from the ossuary in the 1960s by a man who polished it (hence the yellow colour) and kept it at his home, claiming it was the skull of a murder victim. Years later, after this man passed away, it was returned to St Leonard’s with a beautifully-written note and a donation for the upkeep of the ossuary. The skull appears to have been well cared for during its time away from the ossuary, but its theft did raise some questions about security.

Today, chicken wire protects the skulls on the shelves at the back of the crypt, which are more vulnerable to theft and damage as they are obscured from view by the large pile of leg bones.

Other skulls show signs of damage from research techniques – some of them were used for research by medical students in the 19th Century. The skull pictured below has had a whole section cut away. The printed numbering and handwritten notes and gender symbols also date from research carried out in the 19th or early 20th Century (many of the presumed genders of the skulls have been disproved by more recent research). Today, there are much stricter guidelines on the use of human remains for research, particularly if that research will cause damage or destruction to the bones.

It is not very easy to determine the gender of a person from the skull alone, and the disarticulated nature of the remains housed at St Leonard’s do not give researchers the luxury of having complete or nearly complete skeletons to work with. However, there are some features which can help the researcher to identify the gender of a particular skull. The skull below, for example, has marks on it that indicate the presence of very powerful neck muscles – an attribute more commonly found in men.

One of the most well-known skulls in the ossuary has a bird’s nest in it. Birds had got into the building – possibly in the 1940s, when glass from the windows was damaged by bomb blasts – and built a nest in the cavity of a damaged skull.

It’s quite a strange experience, coming face-to-face with so many of Hythe’s long-dead residents. The fact that these bones are here at all is a tale in itself, giving us an insight into the beliefs and practices around the treatment and storage of human remains in centuries past. We might not know the names of these people, but they still have so many stories to tell.

The crypt at St Leonard’s is open during the summer months, please see this link for opening times.

References and further reading

The Ossuary – St Leonard’s Church, Hythe https://www.achurchnearyou.com/church/11961/page/41287/view/

Skeletons at an ossuary reveal Hythe’s hidden history, BBC News, 11th June 2012 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-18396901

Ossuary at St Leonard’s Church, Hythe, Visit Kent http://www.visitkent.co.uk/attractions/st-leonard-s-church-ossuary/169388

Reblogged this on First Night History and commented:

Fascinating post about this collection of human skulls.

LikeLike

Fascinating post.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

What a wonderful place – very gothic! I have heard of ossuaries in Italy, but didn’t know we had any over here. I must check it out sometime, thanks for sharing it.

LikeLike

I too was unaware until quite recently that there were any ossuaries remaining in this country. I’d really recommend a visit to St Leonard’s, it’s a fascinating place.

LikeLike

Amazing place what a fascinating post I must try to pay it a visit! Thanks!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Wonderful! A place to fire the imagination!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Given how the phrase ‘charnel house’ has largely been given over to figurative usage in our era, it’s a delight to read about the real thing. Thank you for this excellent post!

LikeLike

Thank you! It was a fascinating visit; odd, but really interesting.

LikeLike

Wow, Caroline – what an incredible place, and I don’t think I’d ever heard of it before. Quite apart from the history, which is fascinating, I am not at all sure how I would feel in there. Thank you for a fascinating post!

LikeLike

Thank you! It is quite strange being in a room full of human bones but it didn’t feel macabre or spooky at all. It was quite a privilege to meet all those former residents of Hythe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post and what an incredible collection of human relics. No idea a place like this existed in UK.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s a very unusual place – not as theatrical as some of the ossuaries found on the continent, but fascinating all the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Caroline – Another place to add to my “must visit” list!

Back when I was more active in archaeological fieldwork two things which I felt were always the most compelling to examine were fingerprints in prehistoric pottery and endocasts (the imprint of the brain on the inner wall of the skull).

LikeLike

I’ve always loved seeing fingerprints in ancient pottery too – there’s something really evocative about those traces of long-dead people (or in the case of a news story I read recently, the paw-prints of a Roman-era cat found on an old roof tile!)

LikeLike

I’ve read of at least one bone house in Bristol where an old woman lived in. They apparently kept warm by fires made from the bones. They are mostly carbon so burn well – the gauchos of South America also have bone fires. Hence the origin of bonfires?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on texthistory and commented:

A big Ossuary

LikeLike

Goodness! You have done a good job, but I find it slightly creepy. I have just returned from Portugal and there were two similar chapels there – in Campo Maior and another small one in Montemor – do add them to your travel list!

LikeLike

Discovered this by accident on a visit to Hythe today: both the ossuary and the church well worth a visit

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I found this story only now. I have heard about this place, but then forgotten it. Now when read this, I decided that I have to try to visit the place before too long. Thanks for the great article and pictures.

LikeLike