Over a doorway on one of the City of London’s many Wren churches is something really quite special. A large but intricate carving depicts the Last Day – the figure of Christ presides over the dead, who are rising up from their coffins in preparation for the final judgement.

This spectacular carving has not always been at St Andrew. It was at one time situated over the entrance to another burial ground close to the church, the paupers’ cemetery at Shoe Lane, which was located by the parish poor house. Edmund Burke, writing for Dodsley’s Annual Register in 1776, describes the scene:

Over the gate-way of the poor’s-house in Shoe-lane, belonging to St Andrew’s Holborn, which is rebuilt and finished, there is now replaced a group of carving in stone, of the resurrection, which formerly was in the old buildings; although taken notice of by few, it is reckoned very curious, and highly executed; and was done before the reformation; and except that inimitable piece of sculpture above the north gate of the churchyard of St Giles in the Fields, is not to be equalled in England.

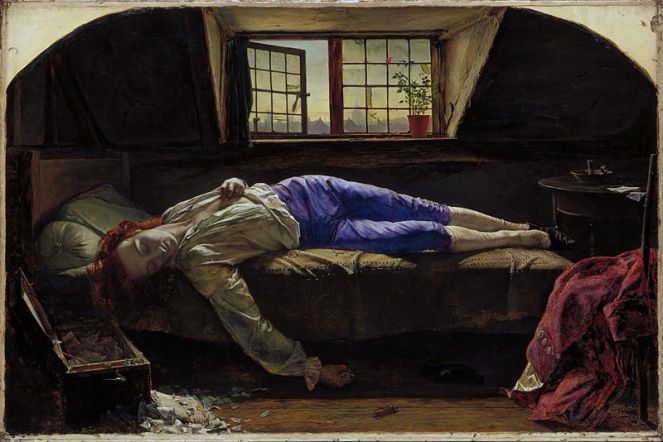

This burial ground, the final resting place for many of the area’s lost and poor folk, was also the burial place of a tragic young poet – although rumours were spread that his body had been exhumed by his grieving family and taken to Bristol. Thomas Chatterton had been a keen writer from a young age, and in the persona of Thomas Rowley, a medieval monk, he wrote poems and histories. He moved from Bristol to London as a young man and although his work gained some recognition, he failed to gain a wealthy patron and became increasingly desperate and impoverished, committing suicide by arsenic poisoning in August 1770 at the tender age of seventeen. His body was found in his meagre lodgings near to St Andrew, Holborn, and he was buried in the workhouse poor ground. Rumours that his family members exhumed his body from the burial ground and took it away to Bristol in the dead of night have never been proved. Chatterton’s work attracted a great deal of attention in the decades after his death, inspiring many Romantic poets and artists such as William Wordsworth, John Keats, Henry Wallis, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The burial ground at Shoe Lane disappeared in about 1839. Isabella Holmes, writing in the 1890s, says that the burial ground “gave way to the Farringdon Market, which, in its turn, has been supplanted by a new street called Farringdon Avenue.” Shoe Lane today is lined with modern buildings – perhaps the dust of those buried near the old poor house is still mingled in the soil of the building site pictured below, which is located between Shoe Lane and Farringdon Street.

St Andrew’s has recently undergone some significant renovations, including the remodelling of the churchyard. The smart new churchyard is now open to the public, so I was able to get a closer look at the resurrection stone.

The carving itself looks as though it’s recently had something of a spring clean – there was no soot or grime obscuring the details of the carved figures. The scene is carved into two separate stones, and the lower stone filled with images of the dead rising again on the last day. Coffins, some containing skeletons, are depicted amid the chaotic jumble of human limbs.

Some of the figures seem to be begging for mercy.

Another figure clings desperately to an angel. The angel is one of the few clothed figures in the scene – the folds of its robe are still clearly visible.

Above the mass of figures, Christ stands surrounded by clouds and winged figures, his arms outstretched and his expression serene.

Beneath Christ’s feet is a defeated, dragon-like beast with a long tail, symbolising the triumph of good over evil.

The carving is thought to date from the 17th Century (although Edmund Burke claimed it was from “before the reformation”). The little winged cherubs or putti (winged babies, often symbolising the omnipresence of God) surrounding the figure of Christ seem to be the giveaway in terms of the date of the carving- cherubs and putti were a common feature in a lot of 17th and 18th Century art.

At first glance, a scene depicting figures breaking out of coffins seems incredibly macabre. But the purpose of this carving wasn’t as a memento mori, a reminder of mortality – the message conveyed seems a more hopeful one. The beautifully carved face of Christ is calm rather than threatening, and he seems to be welcoming the risen figures into his kingdom. Unlike many depictions of the Last Judgement, the image on the resurrection stone doesn’t have a big emphasis on suffering and hell. Instead, the eye is drawn towards the figure of Christ and, through him, the hope of eternal life. It’s a little different from many of the pre-Reformation fire and brimstone depictions of the Last Judgement, such as the 15th Century work by Stefan Lochner, which shows many frightening images of fire and devils torturing the damned. The only monster shown on the resurrection stone at St Andrew, on the other hand, is the one that has been defeated by Christ.

Before the Reformation, many churches in England contained frightening images of the Last Judgement, but few survived the purges that saw churches stripped of their colourful medieval statuary and wall paintings. There are many famous surviving depictions of the Last Judgement, including the famous Michelangelo fresco on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City (pictured below), which was painted between 1536 and 1541. Like the resurrection stone, Christ is the central figure of the piece. The dead are pictured naked, suggesting equality of all in death. This was a departure from older depictions of the Last Judgement, where the dead were sometimes shown in the clothes of their social positions in life.

Another resurrection stone can be found in the City church of St Mary at Hill – this stone has been restored and relocated to the church’s narthex to prevent any damage from the elements. It’s a similar situation at St Giles in the Fields, where a resurrection scene carved in wood stood for many years over the entrance to the churchyard. This too now resides inside the church to protect it from decay and damage. Both of these carvings are thought to date from about the same time as the one at St Andrew, Holborn. It’s not known who exactly carved these stones – perhaps they were the work of the same person, or all came from the same workshop?

The approximate date of these resurrection carvings is interesting – perhaps the person or people who came up with the idea to create them were inspired by the disasters that struck London in the 1660s – the terrible mortality of the 1665 outbreak of plague, and the destruction of the Great Fire of 1666. In the late 17th Century, these events would have remained in Londoners’ minds as the city recovered. Perhaps the stones had a double-edged meaning; a reminder of what was to come on the Last Day, but with a comforting touch (particularly poignant given the stone’s original location in a workhouse burial ground) that reminded the viewer that whatever pain and suffering occured in the temporal world, there was still the chance of eternal life with Christ.

The resurrection stone at St Andrew, Holborn is visible from Holborn Viaduct, and the churchyard is open during daylight hours. Alternatively, the link below will take you to a wonderful 3D image of the carving.

References and further reading

St Andrew Holborn Churchyard, London Gardens Online http://www.londongardensonline.org.uk/gardens-online-record.asp?ID=COL056

Fleet Street: Tributaries – Shoe Lane, Old and New London: Volume 1, 1878 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol1/pp123-135

Edmund Burke – Dodsley’s Annual Register, 1772 (Google Books link)

Mrs Basil Holmes – The London Burial Grounds, 1896

Thank you, thats really interesting, I love these little bits of history dotted around London 🙂

LikeLike

Really interesting. I have seen the stone at St Mary at Hill, but have not seen this one. I will have to visit.

LikeLike

I’m not a believer in coincidence, but last night, I pulled out a CD “From Brush & Stone”,Gordon Giltrap & Rick Wakeman at random, and listened to a track on it it, “The Death of Chatterton”, I had never seen the painting by Wallis until today!

That is the second coincidence this week, the other being seeing prints and engravings by the satirist George Cruikshank, on two different documentaries I watched.

The article on the resurrection stone is, as always, enlightening. Your attention, and examination of the detail is wonderful.

LikeLike

Fascinating, as always. Chatterton is sadly neglected – I rediscovered him as a result of research I did for a ghost sign in Bromley on Chatterton Road, I never found a link to Bromley though.

LikeLike

Thank you! I must be honest, I’d not come across Chatterton until I started researching this post. For such a tragically short life, he certainly made a big contribution!

LikeLike

Gracias!

LikeLike

A delightful article and website, a joy in fact. I had great fun trying to find the Annual Register article by Burke. I finally traced it to the 1766 edition published in 1767 (rather than 1776). The Resurrection carvings are amazing; to me especially because of my interest in Thomas Chatterton. If anyone using your website discovers anything about Chatterton then do please let me know.

LikeLiked by 1 person