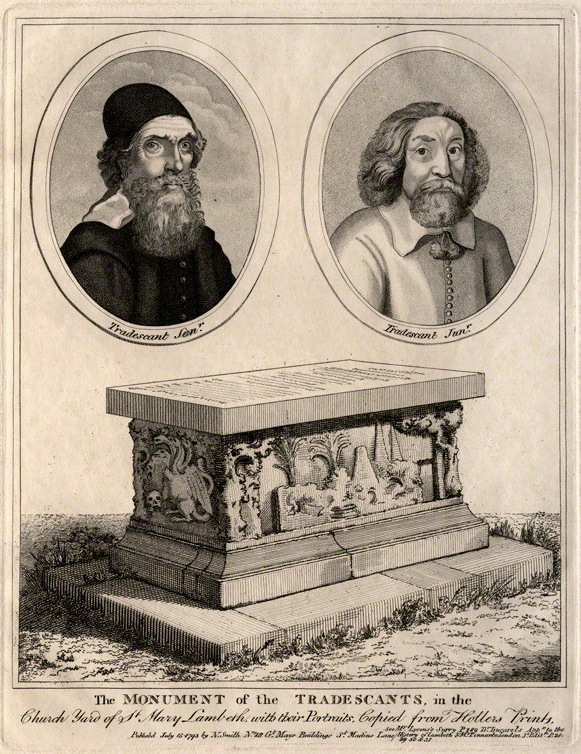

Tucked away in a pretty garden that was once an old churchyard near the River Thames is an extraordinary, richly-carved tomb. Decorated with exotic scenes and creatures, it marks the resting place of members of the Tradescant family, who made a name for themselves in the 17th Century collecting plants and other curiosities from all over the world.

This tomb marks the grave of the Tradescant family, members of whom were celebrated explorers and collectors of plants and artefacts in the 17th Century. They rest in the former churchyard of St Mary-at-Lambeth, which is no longer a church but now houses the Garden Museum. The richly detailed carvings on the Tradescant tomb set it apart as a masterpiece of funerary architecture, and unsurprisingly it has been Grade II* listed by English Heritage. The four corners of the tomb are adorned with trees, and each side depicts a different scene.

The Tradescant family’s coat of arms is on one end of the tomb.

One of the longer sides of the tomb depicts a scene of Classical ruins. The foreground is littered with broken columns, while behind them are arches, pyramids and what might be funerary monuments. It’s a mysterious scene – it’s not clear whether a particular country is being depicted, or if the scene is an allegorical one, or even if it is meant to represent places visited by members of the Tradescant family.

On the opposite side of the tomb an Egyptian scene is pictured – ancient Egyptian ruins stand amongst sand and palm trees, and in the foreground are some shells and a crocodile. Like the Classical ruins on the other side of the tomb, this scene may be alluding to a place visited by the well-travelled Tradescants – John Tradescant the elder certainly visited north Africa whilst travelling to collect plant specimens and exotic artefacts.

On the other end of the tomb are the most macabre and frightening of the carvings. A skull, a common memento mori symbol, is beneath a hydra – a creature with many heads straight out of Greek mythology. The hydra is a sea monster which Herakles fought as one of his twelve labours. Each time one of the hydra’s heads was cut off, two would reappear in its place, making it a truly formidable foe. The hydra can be seen to symbolise the conquest of an enemy – perhaps its position towering over the skull on the Tradescant tomb is a symbol of an eventual triumph over death? Perhaps it was inspired by the famous passage from 1 Corinthians 15:26: the last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.

The Tradescant tomb we see today is not the 17th Century original – the tomb in the garden dates from 1853, when it was replaced with a freshly carved replica (I wonder what happened to the worn old tomb?). A 1773 description of the old tomb in Volume 42 of The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer reads:

This once beautiful monument hath suffered so much by the weather, that no just idea can now, on inspection, be formed of the north and south sides. But this defect is happily supplied from two fine drawings preserved from Mr Pepys’ library at Cambridge.

It was these detailed drawings held at the Pepys Library that allowed the 1853 tomb to be a faithful replica of the 1662 original, although there are some minor differences. In an age where old buildings and gravestones were not always held with the same reverence that they are held in today, the Tradescant tomb was nevertheless unusual and spectacular enough to deserve close attention from those wishing to preserve its dramatic carvings.

The original marble lid from the tomb is now on display inside the Garden Museum. The inscription reads:

“Know stranger ere thou pass, beneath this stone

Lie JOHN TRADESCANT grandsire, father, son

The last died in his spring, the other two

Lived till they had travelled art and nature thro’

By their choice collections may appear

Of what is rare in land in sea and air

Whilst they (as Homer’s Iliad in a nut)

A world of wonders in one closet shut

These famous Antiquarians that had been

Both gardeners to the ROSE and LILLY QUEEN

Transplanted now themselves, sleep here, and when

Angels shall with their trumpets waken men

And fire shall purge the world, these hence shall rise

And change this garden for a Paradise.”

The Tradescant family were as fascinating as the decoration on their tomb. John Tradescant the elder (1750-1638) was a gardener who worked for various members of the English aristocracy, including Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, and George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham. He travelled extensively, collecting rare and exotic plants from all over the world, many of which went on display in the gardens of his masters and also in his own garden at Lambeth, just south of the River Thames. Places John Tradescant visited ranged from Arctic Russia to north Africa and the Levant. In 1630, he began working for King Charles I as Keeper of his Majesty’s Gardens, Vines, and Silkworms at the Queen’s palace of Oatlands in Surrey.

Many of the plants, seeds and bulbs that Tradescant collected on his travels were kept at his “Ark” in Lambeth, which became the Musaeum Tradescantianum. This was the first museum ever to open to the public in England, and as well as showing off plant specimens it contained many other curious and exotic items that Tradescant had collected over the years.

The elder John Tradescant died in 1638, and his son – also called John – succeeded him as head gardener to the King and Queen. Before taking on his father’s old job, the younger John had lived for many years in the colony of Virginia, where he collected plants and trees and described many new species previously unknown to Europeans. He also brought a number of important Native American artefacts over to England, which he added to family collection at the Ark at Lambeth.

John Tradescant the younger died in 1662, and as his son (another John) had predeceased him, he had made an arrangement with the collector Elias Ashmole, who had been acquainted with the family for a number of years, over the future of the contents of the Musaeum Tradescantianum. It was agreed that the collection would be transferred into the ownership of Ashmole after the Tradescants had died.

The agreement with Ashmole apparently stipulated that the collection remain with John’s widow Hester for the rest of her life, but Ashmole took possession of the collection earlier than this and Hester launched legal action against him. The Court of Chancery ruled in Ashmole’s favour. Poor Hester Tradescant, who commissioned the ornate tomb to her husband, father-in-law and stepson at Lambeth, is said to have drowned herself over the whole affair.

The Tradescant collection went on to make up a large part of what became the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford – many of the items remain there to this day as a celebrated part of the museum’s collection. As for Ashmole, he too is buried at the church in Lambeth, but his grave is not currently visible to the public.

The Tradescant tomb is in good company – two other beautiful Grade II* listed monuments can be found in the grounds of the Garden Museum. The first is very close to the Tradescant tomb, and marks the burial place of a sea captain, William Bligh, who famously captain of the HMS Bounty when its crew mutinied in 1789. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the inscription on his tomb doesn’t mention the mutiny, instead choosing to focus to on his voyages to discover the breadfruit and his service in the Royal Navy.

The other Grade II* tomb is close to the museum’s entrance, and marks the burial place of members of the Sealy family, who were involved with the Coade family’s business manufacturing artificial stone. The imposing tomb, which is itself made of Coade’s artificial stone, is topped with an urn, which is elegantly encircled by an ouroboros, a snake devouring its own tail (a symbol of eternity and rebirth). Carved stone flames rise from the top of the urn.

The Garden Museum, where these fantastic tombs are located, is housed in the former church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, which is located close to the Archbishop of Canterbury’s residence at Lambeth Palace. The church was founded in about the 11th Century, and was substantially remodelled during the Victorian period (around the same time that the Tradescant tomb was recarved). However, in 1972 the church was closed and deconsecrated, and for a time this historic building was threatened with demolition. Rosemary Nicholson, visiting the doomed church to see the Tradescant tomb, was shocked by the building’s dilapidated state and in 1977, after repairs to the building were made, the church opened as the Garden Museum. This museum celebrates the history of gardens and gardening, with the Tradescant family playing a prominent role in that story. At present, the museum is expanding and is due to open a gallery dedicated to the Tradescant family in the near future.

The knot garden, where the Tradescant and Bligh tombs are located, is rather fittingly based on 17th Century garden designs that the Tradescants would have been familiar with. The “knot” is made up of low box hedges that are arranged in a pattern, with all kinds of different plants and herbs planted in between. It’s a fitting setting for the final resting place of a family of great gardeners and explorers – considering how close the church of St Mary-at-Lambeth came to being demolished and lost forever, it’s wonderful to visit this peaceful space with its fascinating tombs and its garden design inspired by the gardens of yesteryear.

References and further reading

The Tradescant Tomb, The Garden Museum http://www.gardenmuseum.org.uk/page/the-tradescant-tomb

Tradescant family, The Vauxhall Society http://www.vauxhallcivicsociety.org.uk/history/tradescant-family/

Church of St Mary, Lambeth, in Survey of London Volume 23: Lambeth, South Bank and Vauxhall, London County Council, 1953 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol23/pp104-117

The London Magazine, Or, Gentlemen’s Monthly Intelligencer, Volume 42, 1773 (source)

The Knot Garden, The Garden Museum http://www.gardenmuseum.org.uk/page/our-gardens

One of my favourite graveyards where my ancestors stone can be found http://somerville66.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/searching-for-tombstone-at-st-marys.html

LikeLike

A fascinating article, and another beautiful location. The Tradescant tomb is a magnificent memorial to their work.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing your family connection with this burial ground – really fascinating!

LikeLike

Marvellous! Love the details about the Tradescants. I am taking two books on holiday about them, recommended by someone who read my (brief) post on the Church. See you in October at London Historians…

LikeLike

I must admit I didn’t know much about the Tradescants before I did some research for this post, but they were a really fascinating family.

See you at London Historians soon!

LikeLike

There was a lot more to Captain Bligh than just one mutiny! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Bligh

LikeLike

Definitely – he had quite a career!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating!….from an American with Tradescantia growing in her garden.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Always a pleasure to read your “reports.”

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

What an interesting story! The carvings are amazingly detailed.

LikeLike

I’ve never seen anything quite like it!

LikeLike

Another beautifully researched and fascinating article. On my list of places to visit! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I went to the Garden Museum specifically to see the Bligh tomb, but ended up being more impressed by Tradescant’s, so it’s great to learn more about it! I don’t think I even noticed that hydra when I was there, which is weird since it looks huge!

LikeLike

I think the hydra ends up being in shadow for quite a lot of the time – it certainly made it tricky to photograph when I visited! The Bligh tomb is great but the Tradescant tomb really is something quite special.

LikeLike

Brilliant post…the Tradescant grave is wonderful…and each time I see it I notice a different detail!

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s an amazing monument – one of the best I’ve come across.

LikeLike

Loved it. The contemporary photos v the etching are a joy. Keep up the good work.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

A really fascinating article about a place which I have long been meaning to visit. I had heard that there was a decorative tomb within the grounds and this has really spurred me on.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog and commented:

Wonderful 🐵

LikeLike

Fascinating – would have loved to see and know what happened to the original tomb.

LikeLike

The original tomb’s ‘lid’ is inside the museum, but unfortunately the rest of the tomb hasn’t survived as far as I can tell. It was apparently very worn and probably just got dumped, sadly.

LikeLike