When I visited the churchyard of All Saints, Isleworth, earlier in the year, I’d gone in search of the plague pit there. However, whilst exploring the burial ground, I also came across a headstone that commemorated a person who would probably have disappeared into an unmarked paupers’ grave were it not for the great age she lived to. Mary Hicks, who died in 1870 at the grand old age of 104, spent the last twenty-seven years of her life as an inmate of the Brentford Workhouse.

The workhouse where Mary spent the last decades of her life was located on Twickenham Road, not far from the churchyard at All Saints, Isleworth. The Brentford Union Workhouse was opened in 1837, but a workhouse had existed in the area since the 1750s. The Brentford Union Workhouse was operated by the local Board of Guardians, which represented a number of parishes in the area (before the reforms, workhouses had been the responsibility of individual parishes).

Reforms of the Poor Law in the 1830s had effectively forced anyone unable to support themselves to enter the workhouse by abolishing poor relief for any able-bodied pauper who did not enter the workhouse. The intention was to make the workhouse a place to be feared, a place of last resort, so that people would either seek employment or help from family rather than seeking poor relief from their parish. It’s interesting how many of the debates surrounding the Poor Law reforms of the 1830s are similar to those around who should and should not receive unemployment or incapacity benefits today.

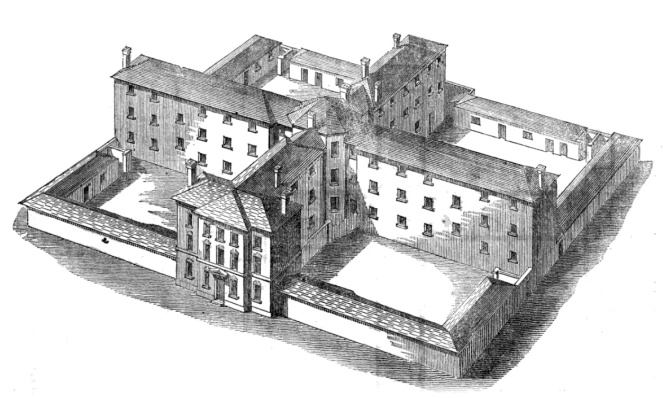

The site of the Brentford Union Workhouse is now occupied by the West Middlesex University Hospital, and no trace remains of the workhouse as it would have been in the years that Mary Hicks was there. We do, however, know what it would have looked like. Similar to other workhouses built in the 1830s, the Brentford Union Workhouse was designed on a cruciform plan, similar to the image below, which had four wings and provided separate yards for men, women, boys and girls. Such a forbidding structure, its design influenced by Jeremy Bentham’s ideas of a prison “panopticon”, would have been intended to act as a deterrent to the would-be workshy. To those unfortunate souls residing inside, it must have felt like a prison.

The demographics of those residing in the workhouse changed as the Victorian period wore on. In 1867, when Mary Hicks was still alive, about half of all the inmates in London’s forty workhouses were “old and infirm.” (Longmate, The Workhouse, p137) By 1900 the majority of people in the workhouse system were either sick or elderly, and in 1929 legislation was passed to allow local authorities to convert workhouse infirmaries into municipal hospitals. Any last vestiges of the workhouse finally disappeared for good with the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948.

All of this was a long way in the future when Mary Hicks was alive. Mary and her husband John both entered the workhouse at Brentford in June 1843. John Hicks died in June 1848, at the age of 66, but Mary lived on. I wonder what circumstances took them to the workhouse; perhaps one of them – most likely John, given his earlier death – became infirm and unable to work any more. State pensions did not exist in the 19th Century and anyone who was unable to work to support themselves, and had no other source of income, would have been at risk of having to enter the workhouse.

![The men's dormitory at the former Southwell workhouse, Nottinghamshire (image by [] on Flickr, used under a Creative Commons licence)](https://flickeringlamps.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/6162837527_4daed57418_o.jpg?w=663&h=372)

When Mary died on 24th November 1870, her great age attracted interest from the press, and coverage of her funeral appeared in the newspapers. The funeral itself sounded like quite a grand affair – quite possibly the grandest funeral of anyone who ever died within the walls of that sad workhouse. Many local people turned out to witness her burial. Other aged inmates of the workhouse were present, as well as members of the Board of Guardians, who paid for the gravestone that can still be seen in Isleworth churchyard today. The Chelsea News and General Advertiser carried the following story on 3rd December 1870:

At the weekly meeting of the Brentford Board of Guardians on Monday, it was reported that Mary Hicks, aged 104 belonging to the parish of Isleworth, died on the 24th November. She was the widow of John Hicks, aged 66, who died on the 27th June, 1848. Both were admitted into the workhouse on the 26th June, 1843. The deceased Mary Hicks was born on the 11th August, 1766, and was baptized on the 15th February, 1767, at Broseley Church, Salop. Since her admission into the workhouse, now over twenty-seven years ago, she had fared well, and was a very hale woman, even after she had lived a century. She retained all her faculties to within a short time of her death, and would walk about with the aid of a stick. Her remains were interred in Isleworth churchyard yesterday afternoon, on which occasion several of the guardians attended. Four inmates followed, whose united ages amounted to 335 years (being an average of 83 years), with four other inmates, whose united ages, added to the above, amounted to 628 years, being an average for the eight of 78 years. The scene in the churchyard drew together a large concourse of spectators.

This report suggests that Mary, or at the very least the great age she lived to, was respected by the guardians and her fellow inmates. The elderly inmates who attended her funeral might have been her friends; it’s likely that many of them also spent many long years in the workhouse.

There is, however, a twist in the tale. Whilst researching this article, I came across a digitised version of an old book entitled Human Longevity: Its Facts and its Fictions, including an Inquiry into Some of the more remarkable instances, by William John Thoms, originally published in 1873. In this book, Mr Thoms investigates claims of longevity and seeks to prove or disprove these claims using archival research and information gathered from relatives of the people concerned. The case of Mary Hicks is one of those that he investigates, and he concludes that Mary may not have reached her 100th birthday after all. He contacted her relatives, and studied baptism records in her home parish of Salop in Shropshire. It was among the baptism records that he found evidence for a mix-up that might have led to Mary’s age being entered on the workhouse records incorrectly. Mary was born Mary Roden, and Thoms found evidence of two Mary Rodens baptised in Salop – one in 1767, and one in 1773. Information from a relative of Mary Hicks suggested that her parents were called John and Sarah Roden, and their daughter Mary was the one baptised in 1773. In this time of vaguer records Mary Hicks may not have been aware of her true age, and it’s easy to see how a mix-up between two people of the same name could have been made. Even if Mary Hicks was only 97 when she died, she still lived an extremely long life – a remarkably long life given the tough conditions she lived in.

The care of the elderly and infirm continues to be a subject for much debate today – with Britain and many other countries having an ageing population, it is incredibly important that the appropriate care will be available and accessible to those too old or unwell to care for themselves. Poor Mary Hicks lived for almost three decades in surroundings that today we would consider unimaginably poor and sad, even cruel. Unlike thousands of her fellow elderly workhouse inmates, we only know Mary’s name thanks to the gravestone that Brentford’s Board of Guardians provided for her. Her story is a sad one, and I found myself feeling thankful that today, despite all the difficulties faced by our healthcare systems in Britain, that there is a more compassionate approach to society’s oldest and most vulnerable people.

References and further reading

Norman Longmate – The Workhouse, Temple Smith, London, 1974

Brentford, Middlesex – Workhouses.org.uk http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Brentford/

Designing the workhouse: Cruciform buildings, The Victorian Web http://www.victorianweb.org/history/poorlaw/design1.html

Entering and leaving the workhouse – Workhouses.org.uk http://www.workhouses.org.uk/life/entry.shtml

William John Thoms – Human Longevity: Its Facts and its Fictions, including an Inquiry into Some of the more remarkable instances, 1873 https://archive.org/details/b21911769

Very interesting! Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Another fascinating slice of history. Thought provoking, too, as with my disabillity, I’d probably be a workhouse inmate myself, were this 1815.

LikeLike

It’s a sobering thought, isn’t it? So sad that people like Mary Hicks ended up in the workhouse simply because they had no pension and nowhere else to go.

LikeLike

Interesting story – I was thinking that that was an unusually big age gap between husband and wife, 16 years, she would have been 82 when he died at the age of 66 but if the birth dates were mixed she was only 10 years older.

LikeLike

Yes, I thought that too!

LikeLike

A fine article. You British were a little more fortunate in that a mor humane regime existed in your country since Eliz 1st. Dean Swift regularly railed against the lack of consideration or a similar Poor Law system for his adopted Dublin where the poor of other counties would flood the capital begging thieving or what ever it took to survive. Eventually long after his death the British govt. introduced the Poor Law Unions on a county wide basis around 1834. Most Irish like other nationals would shun the Poor House contrary to what’s suggested in the article. The financing of these establishments was done partly through a rates being struck which had to be met by the wealthy or snug farmer or the town traders. These affluent people resented having to meet this expense and accused the unfortunates who were on their last legs from malnutrition, of being lazy wastrels and parasites. Often the work these people were asked to do was meaningless. This was a sore point to Dargan the rail engineer who helped construct the Irish Rail System. He sought without success to have these unemployed build the railway and give them some dignity. The notorious Gregory Clause was introduced in 1847 in the height of the Great Famine. This law demanded forfeiture of peoples homesteads down to the quarter acre, before they and their families could access the poor house. If like Miss Hicks they survived the ordeal which at the time was unlikely, when they got or were put out, they had no place to go. this is often referred to as the Great Silence as it was largely gombeen businessmen and snug farmers availed of these peoples misfortunate circumstances and took over their homes and little farms. Tralee Poor House records in the county Library make reference only to the month to month costs of bedding coal foodstuff etc. A childs name would be mentioned only if they misbehaved and the punishment recorded. Many died in paupers graves and that same Poor House took up very little of the offers of assisted passage to the colonies or Canada, because the ratepayers were biding time hoping the government would incur the entire costs. The Poor House or as it was also known became the Workhouse and afterwards became the primary hospital for Tralee.

LikeLike

Thank you! I was unaware of the history of the poor house system in Ireland, how awful that people were forced to give up their farms before they could be admitted to the poor house – talk about forcing people into a cycle of poverty and dependence that they would really struggle to get out of.

LikeLike

This is marvellous!

LikeLike

Thanks Sheldon!

LikeLike

Very interesting! (and well told & researched, I might add!)

I’m a recent subscriber and have been enjoying the work you

put into these posts. The photos, layout, everything. I’m looking

forward to the next one! 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Well researched and fascinating – thanks for posting. I understand a lot more about what life in the workhouse was like – scary. Even wit the mix-up over Mary’s actual age, 97 must have been a good innings at that time.

LikeLike

I’ve been meaning to investigate the Brentford workhouse and this has provided the motivation to start me off again. You may have seen the memorial to Alice Ayers in Isleworth Cemetery just up the road from All Saints; I recently discovered that a few years that was erected (by public subscription) Alice’s mother was taken in by the Brentford workhouse so wondered if her grave might be marked in any way. Makes you think that the memorial fund might have been used more charitably. Back to the LMA!

(Regarding an earlier comment, the age gap between Mary and John might have been the result of Mary being John’s second wife. As there was a such a high incidence of maternal death in childbirth a widower might very well take another wife, as Victorian fiction so often records.)

Great blog btw.

LikeLike

Thank you for this information. My 4xGreat grandmother Frances Robson died in the Brentford Union Workhouse in 1861, age 93, so she probably knew Mary Hicks.

LikeLike