30 St Mary Axe – better known by its nickname “The Gherkin” – is one of the most distinctive skyscrapers in London. It stands on the site of the old Baltic Exchange, which was badly damaged by a Provisional IRA bomb in 1992 and subsequently demolished. It was during excavations taking place prior to the construction of the Gherkin that, in 1995, the skeleton of a Roman Londoner who had lain undisturbed for 1,600 years was discovered.

On Bury Street, on one side of the skyscraper, there is an open paved area with seating and sculptures. On the side of one of the low, smooth walls that double up as seats is a quite unexpected inscription – it marks the site of a grave. The inscription is in both English and Latin:

To the spirits of the dead

the unknown young girl

from Roman London

lies buried here.

The skeleton discovered on the building site in 1995 was of a young girl, aged between 13 and 17 years, who died some time between 350 and 400AD. She was discovered lying supine, with her arms crossed over her body. Pottery found close by helped to date the burial. It doesn’t appear that she was buried in an established cemetery, as hers was the only burial discovered, but the site would have been outside of the Roman city’s boundaries, as Roman tradition dictated that no burials took place within urban areas.

It’s interesting to note that she is not described as a Roman, but rather as a Londoner. There was nothing found with the burial that could ascertain her identity, and she could have been anyone at all: a Roman citizen, a slave, even a visitor from somewhere else altogether. We will never know.

In April 2007, the girl was reburied close to where her body had been found, at the request of the company who developed the Gherkin. A special funeral service, with the Lady Mayoress of the City of London present, took place at St Botolph’s Church, Aldgate, after which the casket was processed through the streets to the burial site. Music was played as the girl was reburied, in keeping with what we know about Roman funeral rites from the time. A simple plaque with a laurel wreath decoration marks the burial spot.

The girl buried at St Mary Axe is not the only Roman individual to have captured the imagination of Londoners. Archaeologists have revealed some stunning finds from Roman London in recent years, largely thanks to excavations that have taken place prior to large construction projects – like that of the Gherkin – or during construction of the new Elizabeth Line. Among these finds the burials of two individuals in particular have attracted attention.

The redevelopment of the area around Spitalfields Market in the 1990s uncovered a large section of the Roman cemetery that lay to the east of Londinium. Discoveries of Roman artefacts had been made on the site over several centuries, and when given the opportunity to excavate the site on a large scale, archaeologists discovered a large number of burials from a number of time periods, including many from the Roman period. One such burial, uncovered in 1999, was found in a beautiful lead coffin, decorated with scallop shells.

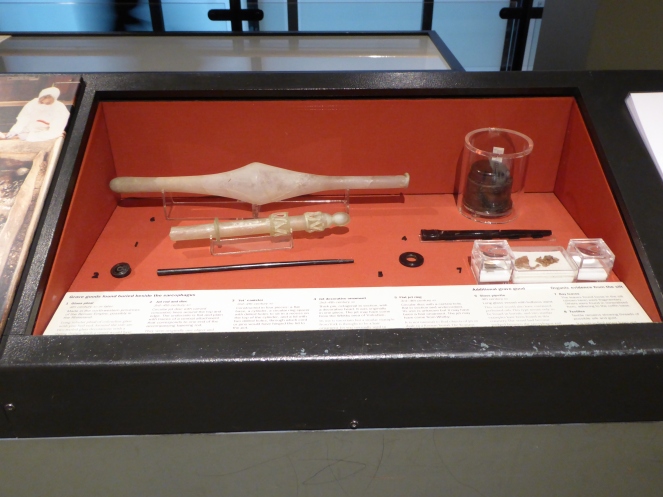

Within this coffin archaeologists found the remains of a woman, and various items which had been placed in the coffin with her to accompany her into the afterlife. These grave goods included some remarkable survivals – fragile glass artefacts, and striking ornaments made of jet. A layer of silt beneath the skeleton contained remains of the bay leaves her head had been cushioned on when she was laid in the coffin all those centuries ago.

Tests on the skeleton, the coffin and the grave goods enabled researchers to paint an image of this woman’s life. She had died young – probably in her early twenties, and tests on her teeth determined that she had not grown up in London, but in Rome. Traces of expensive fabrics were found in the coffin, and this – along with the grave goods found alongside her – demonstrates that she was very wealthy, and probably moved in London’s richest and most powerful circles. Although the official religion of the Roman Empire was Christianity at the time the woman died, in about 350AD, there was nothing among the goods buried with her to suggest that she was a Christian, and some archaeologists have put forward a theory that she might have been a part of the cult of Bacchus, the god of wine. This theory came about when a glass vessel very similar to one found with the Spitalfields lady was discovered in France, filled with wine. However, there is no way of knowing for certain.

The discovery and analysis of the lead coffin and its occupant were featured on the BBC television programme Meet the Ancestors in 1999, and specialists were commissioned to create a reconstruction of what the Spitalfields lady may have looked like, based on the shape of her skull. I was only a kid when Meet the Ancestors first aired, but the unveiling of the reconstructed face of this lady is something I remember clearly – it was amazing. Her face is now on display alongside her coffin at the Museum of London, and visitors often linger there, looking at the likeness of someone who lived in London 1,600 years ago.

In 2006, archaeologists working at St Martin in the Fields, close to Trafalgar Square, discovered an impressive limestone sarcophagus containing the skeleton of a man. It was initially thought that the sarcophagus had been reused for a later burial, and that the man resting within had probably died within the last two hundred years or so. However, when the skeleton was analysed, the results were quite remarkable. This man, thought to be middle-aged when he died, was the original Roman occupant of the stone sarcophagus. The presence of the sarcophagus suggests that he was a high-status and probably wealthy individual. The date of the man’s death – some time between about 390 and 430AD – led to his being given the rather romantic nickname of “London’s Last Roman.” His is the latest Roman burial to have been found in London so far.

What does this man and the nature of his burial tell us about the last years of Roman London? Other items excavated close to where the Last Roman was found dated from the Anglo-Saxon period, giving archaeologists a rare and precious insight into what London might have been like in the first decades and centuries after the Romans left Britain. Londinium’s light had been on the wane for decades; many of the city’s major civic buildings were demolished at the beginning of the 4th Century, and the population was lower than its 2nd Century peak. It’s generally agreed that after the Roman Empire officially left the province of Britannia in 410AD that Londinium was gradually abandoned and fell into ruin, with the Saxon settlement of Lundenwic being founded further to the west in later centuries. However, just because Roman troops and bureaucrats left Londinium in 410 doesn’t mean that all of the city’s inhabitants followed them back to continental Europe. A Roman kiln was uncovered close to where the Last Roman was found buried – a perhaps unexpected find in a place so far west of the Roman city, but an indication that people were still living and working in the area even at a time when the city was in decline. The man buried there may have been a Christian – if so, the site where the church of St Martin in the Fields now stands may have been a Christian site for much longer than previously thought.

Unlike the girl who was reburied at St Mary Axe, the Spitalfields lady and the Last Roman were not able to be reburied close to the sites of their original graves. Both individuals are currently residing at the Museum of London’s special facility for storing human remains, in the basement of the museum itself. The bones of thousands of Londoners from many different time periods can be found in the bone archive, with row after row of neatly shelved and labelled boxes, each containing the mortal remains of someone who once lived in London. So much has been discovered about London’s past through the study of these bones. Many of these skeletons are eventually reburied, in cemeteries outside of London, with care taken to give them a dignified and appropriate burial.

The burial of the Roman girl at the Gherkin, then, is an unusual sight. There are few marked graves of any age left outdoors in the City of London; its churchyards have been closed since the 1850s, with their worn old tombstones moved or taken away. When I visited the grave site whilst researching this article, many passers-by stopped to read the inscription above the grave. We can’t know what sort of grave marker this girl may or may not have had when she was first buried, but today her memorial prompts 21st Century Londoners to pause and think of those who made this wonderful city their home many centuries ago.

References and further reading

Roman girl’s remains return to City of London Resting Place, Foster and Partners, 17th April 2007 http://www.fosterandpartners.com/news/archive/2007/04/roman-girls-remains-return-to-city-of-london-resting-place/

Remains of Roman teenager buried, BBC News, 17th April 2007 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/6563909.stm

Plaque: Roman girl, London Remembers http://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/roman-girl

Roman lady’s coffin shows 4th century élan, Maev Kennedy, The Guardian, 16th April 1999 http://www.theguardian.com/uk/1999/apr/16/maevkennedy

Coffin reveals secrets of a Roman lady, BBC News, 15th April 1999 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/319833.stm

How we solved the mystery of the Roman ‘princess’, History Extra, 30th September 2015 http://www.historyextra.com/article/romans/how-we-solved-mystery-roman-princess

Bridging London’s lost centuries, BBC News, 4th June 2007 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6700149.stm

The Last Roman Londoner at the Museum of London, Culture24, 25th May 2007 http://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/art47613

I only came across the Gherkin reburial and inscription last summer and so thank you for explaining the history behind this. I have seen the Spitalfields market remains display and the reconstructed head in the Mof L many times but thanks for linking these finds together in this article and adding the St Martins find in too as I didn’t know about this! Another illuminating article from Flickering Lamps!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Another great post! We kindly received a subscription to “National Geographic” magazine from my in-laws for Christmas 2015 – the February 2016 issue’s cover story was “Under London” and had some great photos and description of some of the artifact discoveries, including those from the Roam era

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/artifacts-found-under-london-archaeology-text

Keep up the great work!

LikeLike

Thank you! There have been some wonderful archeological discoveries made in London in recent years – I am particularly looking forward to seeing more of what was found at the Bloomberg site.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing those histories. I met the Spitalfield lady when I was 13, but I havenever forget her…

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I’m curious, why couldn’t the Gherkin girl be tested as the Spitalfield’s lady was to know more about her?

LikeLike

I suspect that it simply came down to budget restraints – the tests carried out on the Spitalfields lady, and the facial reconstruction in particular, were time consuming and expensive and there may not have been the funding in place to carry out similar tests on the Gherkin girl. It would have been amazing to see what she would have looked like when alive.

LikeLike

I have always wondered about Roman London and if it was very important. I guess not when compare with the larger cities in the empire but locally it probably was. I’d love to see DNA analysis of some of the bodies.

LikeLike

I think Londinium waxed and waned in importance during the Roman period; archaeological evidence seems to suggest that its population reached a peak during the 2nd Century. Some of the Roman skeletons uncovered by archaeologists have been DNA tested (http://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/archaeology/art541900-museum-london-roman-archaeology-dna-harper) and the Museum of London is hoping to test more bones in the future.

LikeLike