A few weeks ago, I went to Brompton Cemetery again. I was with my friend Sharon, a fellow graveyard explorer, and I also had a new camera lens to put through its paces. Since my last visit, a lot of the undergrowth that had swallowed up a good many gravestones had been cleared, and as a result we came across many graves that I’d never seen before. Last time I wrote about Brompton, I felt that I’d not been able to do the place justice in just one article, so it seems like a good time to revisit the cemetery and look at more of its rich heritage. Some of the graves featured this time around are grand and mysterious, others are modest and unassuming; yet all of them have their own fascinating stories to tell.

One grave initially caught my eye because I thought it looked a little old-fashioned in a Victorian cemetery. The typeface of the words inscribed on the grave is more commonly seen on graves dating from the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th Centuries. The grave of Mr Jonathan Glossop is indeed one of the earlier graves to be found at Brompton – dating from 1844 (the cemetery opened to burials in 1840) – but on closer inspection of the headstone’s inscription I realised I’d stumbled across a fascinating story. Jonathan had been a military man, and was a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo. There are many, many military graves at Brompton, but Jonathan Glossop’s must be one of the oldest.

Corporal Glossop served with the 1st Life Guards, a cavalry regiment that – as the inscription on Jonathan’s grave points out – “were so nobly distinguish’d at the ever memorable battle of WATERLOO.” The 1st Life Guards played a dramatic and important part in the victory over Napoleon at Waterloo – they led the famous charge against the French heavy cavalry and driving back the French advance. Jonathan was wounded during the battle – whether this led to a lifelong disability, or even contributed to his relatively early death in his fifties, we cannot know. In many ways, for me, Jonathan’s grave raises more questions than answers: what was his life like after the battle? Did he stay with the Life Guards, or did his injuries force him out of the armed forces? Although much of the inscription on his grave concerns his military career, the final note says something about Jonathan as a man: “He was an affectionate Husband, a Kind Father and Sincere Friend.” These final words perhaps reflect how his family wished to remember him – a war veteran, but also a much loved family member.

Later in the 19th Century, when only a handful of Waterloo veterans were still living, surviving “Waterloo Men” sometimes became quite well known. This photograph, taken in 1880, shows five Chelsea Pensioners who had served at Waterloo – they were regarded as local celebrities and the press would record how these men commemorated June 18th, the anniversary of the battle.

Many of the graves at Brompton hint at lives lived in far-flung corners of the world – a testament to how the world was shrinking in the 19th Century. It would not just have been members of the armed forces who travelled to far-off places – there are examples at Brompton of British people who travelled the world, and of people from abroad who made their homes in London.

The image of Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of death, caught my eye on this otherwise quite unassuming headstone. This memorial marks the grave of Joseph Bonomi, yet another well-travelled individual to be laid to rest at Brompton, and his family. Tragically, the grave has the names and ages of several small children who died young – four children aged between eight months and ten years who died in a single week in 1852, victims of whooping cough. An appalling tragedy for any family to have to endure; a few years later, the children’s mother died at the age of just 34, leaving Joseph to bring up their eight surviving children alone.

Joseph Bonomi made a name for himself as an Egyptologist and artist, accompanying expeditions to ancient sites in Egypt and gaining a reputation for producing extremely accurate drawings and diagrams of the incredible old structures and artefacts to be found there. He spent many years in Egypt, returning to London in the 1840s where he worked to catalogue collections of ancient Egyptian artefacts, including those at the British Museum, and also eventually became the curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum, a post which he held from 1861 to his death in 1878.

Bonomi’s father and brother were well-respected architects, and Bonomi himself also had some talent in that direction. He designed the Egyptian Revival gateway at Abney Park Cemetery, and the remarkable facade of the offices serving the Temple Works flax mill in Leeds, which opened in 1841. The Egyptian Revival craze was at its height in the first half of the 19th Century, when Bonomi was working in Egypt and London, and when the Crystal Palace was moved from Hyde Park to Sydenham Hill in 1854 he helped to design the Egyptian Court that was a part of the permanent exhibition there.

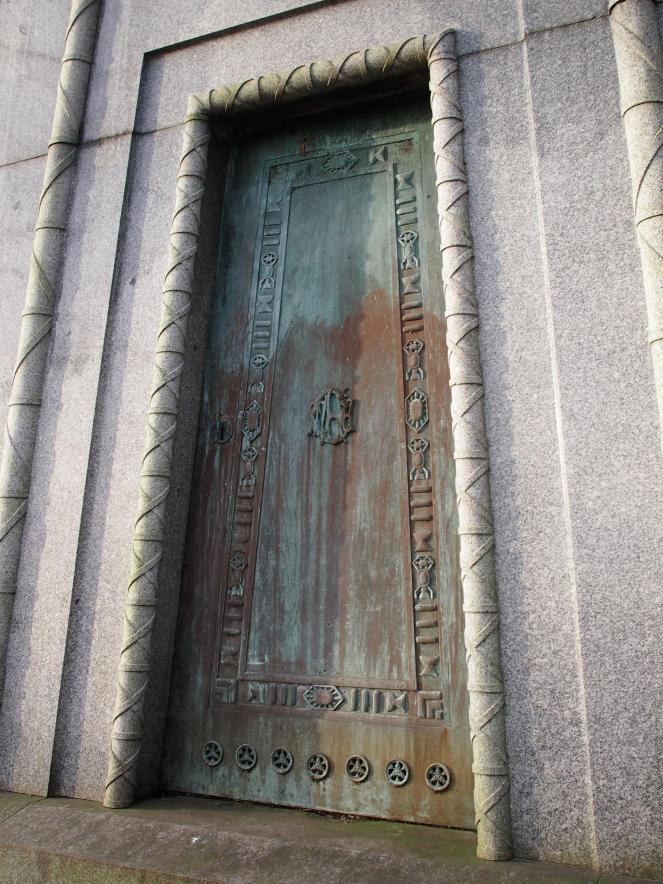

One of the most mysterious monuments at Brompton has many strange stories and theories attached to it, and has been linked to Joseph Bonomi, whose grave is situated nearby. The imposing Egyptian Revival-style mausoleum of Hannah Courtoy has earned itself the bizarre reputation of being Brompton Cemetery’s “Time Machine”.

Hannah Courtoy is a shadowy figure; little is known about her origins or her life, and the Friends of Brompton Cemetery’s website describes her simply as a “mysterious society lady with fabulous wealth.” She is not thought to have ever married, but it is through her connection with John Courtoy that she acquired her reputed wealth. It’s possible that she was his mistress, and he may have been the father of her three daughters, two of whom were buried at Brompton with their mother. There are rumours that Hannah may have also been a mistress to royalty.

The key to the mauseoleum has been lost, meaning that no-one can get inside, and it is this that has fuelled the rumours that the tomb may be more than it appears to be.

Set a little apart from other graves, the mausoluem occupies a little “island” around which the cemetery path curves – a prominent and no doubt expensive spot for a tomb. It was not complete when Hannah died in 1849, and she was only interred there in 1854 when the monument was finished. Unlike many of the other grand monuments at Brompton, no plans for the tomb survive – this is one of the things that has encouraged the conspiracies around it.

One theory about the mausoleum is that Joseph Bonomi, who did design other Egyptian-inspired structures including at least one tomb, was the designer of the Courtoy mausoluem. Another man, Samuel Warner – also buried nearby, but in an unmarked grave – was an inventor and some allege that he too played a part in the design of the tomb. One story goes that he and Bonomi were involved in the occult, and that through this they had discovered the secret of time travel. Warner’s death in mysterious circumstances in 1853 has led some to argue that he was killed because of what he discovered while working on his inventions.

The story about the mausoluem being a time machine first made it into print in an American newspaper in 1998, and since then the web has been full of discussions, blogs, articles and analyses of the possibility that behind the doorway decorated with scarabs is a secret so far unrevealed. Another theory about the mausoleum is that it is not a time machine but a teleportation device, and that similar tombs in other cemeteries in London could perform the same function.

The idea that Hannah Courtoy’s tomb is a time machine – a kind of stone-walled Tardis – has been fermenting for years. It is based on a volatile mixture of historical fact, supposition, and unfettered flights of the imagination. (source)

I have only really touched very briefly on some of the theories and conspiracies that surround the Courtoy tomb – a quick web search about the tomb brings up all sorts, with varying degrees of sensation. Even if it did turn out that none of the time machine conspiracies have any basis in fact, the stories that have grown up around this mausoleum have given it – pardon the pun – a new lease of life and it continues to draw visitors and provoke discussion to this day.

Brompton is such a rich source of stories, history and architecture. I have visited the cemetery many timea and each visit brings to my attention graves I’ve not seen before, with their own tales – some sad, some exciting, all very human.

References and further reading

Brompton Cemetery – notable monuments http://brompton-cemetery.org.uk/notable-monuments/

Life Guards – National Army Museum http://www.nam.ac.uk/research/famous-units/life-guards

Joseph Bonomi (1798-1878) – drawings and watercolours in the archive of the Griffith Institute http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/4bonomi.html

A correspondence with the history of Egyptology, British Museum blog, 28th September 2012 https://blog.britishmuseum.org/2012/09/28/a-correspondence-with-the-history-of-egyptology/

Is the secret of time travel lurking in a London cemetery? Daily News, 28th October 1998 https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=JXNTAAAAIBAJ&sjid=MIYDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6611%2C2713375

Other Flickering Lamps articles about Brompton Cemetery

At first I was upset that you didn’t mention the flaming Zeppelin tombstone, because that’s my favourite one, but then I realised you had a whole post on it! It was good to learn more about the story behind it! And of course, you highlighted some worthy graves in this post as well; I always learn something new and fascinating on your blog!

LikeLike

Yes, the Warneford grave is one of my favourites too and I felt that it deserved its own post! Honestly, I have so many photographs from Brompton from various visits and there are so many notable and interesting graves that I could write post after post about them all. It’s a wonderful cemetery.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s been a very long time since I was last in Brompton Cemetery so much enjoyed this article, especially the time machine mausoleum which I did not know about. In fact the last time I was in the cemetery it was being used for very unholy purposes in its more quiet corners.

LikeLike

My grandad is buried here. Sadly, a long time after, my Nan was not as there was no space. She had to go East Sheen. Have not been to Brompton Cemetery for years. Hope to some time this year.

LikeLike

I’d like to see a picture through one of those holes on top of her grave.

LikeLike

I’m sure someone has attempted that at some point!

LikeLike

This has only just popped up for me (Sept 2017). Worth waiting for. Most interesting blogs.

LikeLike