Although the 19th Century is the most notorious period for desperate overcrowding in the churchyards and burial grounds of London, the problem of finding enough space to bury the city’s dead was not a new one. As London grew both in population and size during the 18th Century, little room was set aside for cemeteries and the garden we are visiting today is the first example of Anglican churches being forced to locate their burial grounds in far away from the churches themselves. Today, St George’s Gardens in Bloomsbury is very much a part of central London, but when the two burial grounds that were later landscaped into this pleasant park were first opened, they were surrounded by fields.

Following the catastrophes of the 1660s, when London was hit first by plague and then by fire, the city recovered and flourished. By 1700, over half a million people lived there, both inside the old city walls (the modern Square Mile) and in the neighbouring city of Westminster and the surrounding suburbs. A growing population meant that there was a demand for new parish churches, and new burial grounds to accommodate growing numbers of the dead.

In 1711, an ambitious plan was unveiled. The Commission for Building Fifty New Churches was approved by Parliament and set out to build new Anglican churches in London, in part to accomodate London’s rising population but also as an attempt to stem the increasing number of nonconformist churches in and around the city. Although falling far short of the fifty hoped-for new churches – only twelve were built, in the end – the new churches brought about by the Commission certainly made an impact on London’s built environment. Known as the Queen Anne Churches after the monarch on the throne at the time the Commission was started, six of the twelve new churches were designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, pupil of Christopher Wren.

One of the churches commissioned was the church of St George, Bloomsbury, which was to be the last London church designed by Hawksmoor. Its unusual tower, topped with a statue of King George I, was immortalised in William Hogarth’s famous engraving of Gin Lane.

The Commission also took over a chapel that had been built on Queen Square between 1703 and 1706. Originally designated as a chapel of ease to St Andrew, Holborn, the church was designated as a parish church in its own right in 1723. It was dedicated to St George, due to one of its trustees’ governorship of Fort St George in India, but is officially known as St George the Martyr to differentiate it from St George, Bloomsbury.

What both of these new churches had in common – as well as the saint they were dedicated to – was a lack of space for a churchyard. St George’s Bloomsbury was particularly hemmed in by surrounding buildings. Therefore, the novel step of setting up a burial ground for parishioners away from the two churches was taken. Other cemeteries not adjacent to churches already existed in London – Bunhill Fields being a notable example – but the burial ground for the two St George’s was the first Anglican burial ground in London to be situated away from the churches it served.

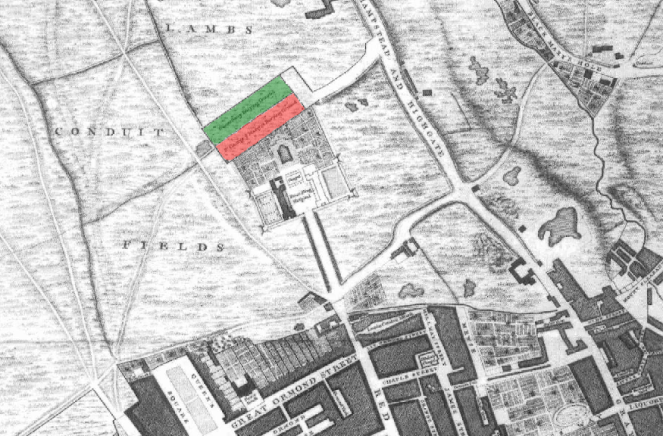

A piece of land was acquired just to the north of Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital, itself situated a little to the north of what was then Bloomsbury’s built-up area. The map below is a section of John Rocque’s famous 1746 map A plan of the cities of London and Westminster, and borough of Southwark, showing the Bloomsbury area around thirty years after the burial grounds were opened. Each parish had their own clearly designated section – it is thought that Hawksmoor may have played some part in the design of the cemetery. The section for St George’s Bloomsbury is indicated in green, with St George the Martyr indicated in red.

Interestingly, the first burial to take place in this new cemetery in Bloomsbury was of one of the men who had been instrumental in bringing about the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches. Robert Nelson was a respected churchman and a philanthropist, and one of the original commissioners for the Fifty New Churches. The idea of being buried in a cemetery some distance away from one’s church was initially unpopular with parishioners of the two new churches. In an attempt to encourage people to buy plots in the new burial grounds, Nelson himself declared that he would be buried there following his death, and after he died in 1715 he became the first person to be buried in the section of the ground belonging to St George the Martyr.

Nelson’s imposing memorial is still there today, and his burial had the desired effect: the burial grounds became fashionable, and the number of grand memorials that survive today show that many wealthy and influential local families chose to be buried there. By the time the two burial grounds were closed in the 1850s as a result of the Metropolitan Burials Act, they were overcrowded, packed with thousands of burials, many in unmarked graves.

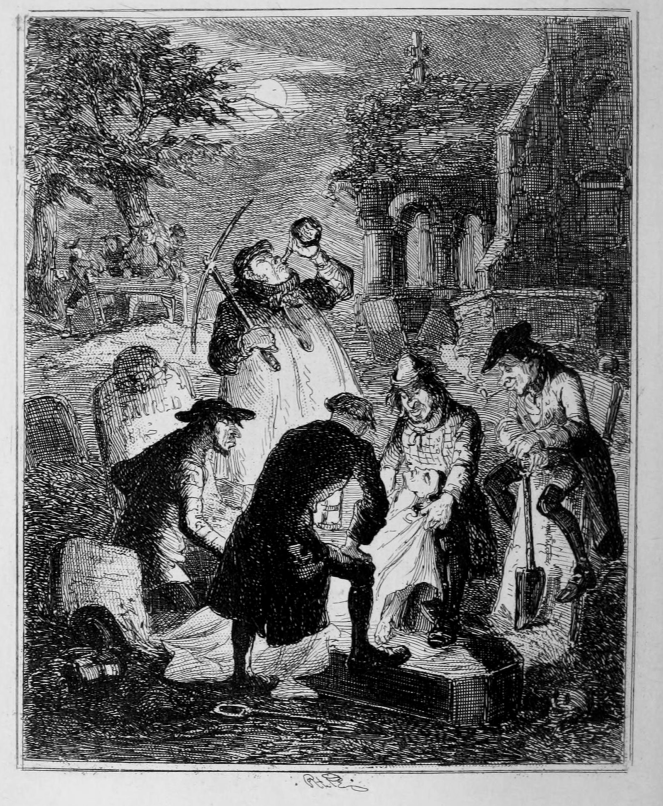

One of the reasons why people had initially been unwilling to bury their loved ones at St George’s Gardens was the fear of bodysnatchers. The burial ground was situated out in the fields, away from people’s homes, and although it was surrounded by a high brick wall people were afraid that bodies would be stolen from the cemetery and sold for dissection. Their fears were not unfounded; in 1777, two men – John Holmes and Peter Williams – were caught in possession of a corpse that they had just dug up from St George’s Gardens. John Holmes was actually employed by St George’s Bloomsbury as a gravedigger, which would probably have meant it was easy for him to access the burial ground at night. Along with a female accomplice, Esther Donaldson, they were taken to court by the widower of the woman whose body they had stolen, and Holmes and Williams were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and were also publically whipped.

Despite the threat of bodysnatchers, the burial ground proved to be popular as the 18th Century wore on, and many impressive monuments were raised there. One of these graves was of a granddaughter of Oliver Cromwell. Anna Gibson, who died in 1727, was the sixth daughter of Richard Cromwell, who briefly succeeded his father as Lord Protector before the monarchy was restored in 1660.

A tall, quite stout obelisk dates from 1729 and was either sculpted by, or raised in memorial to, a man called Thomas Falconer (while researching this post I found conflicting reports).

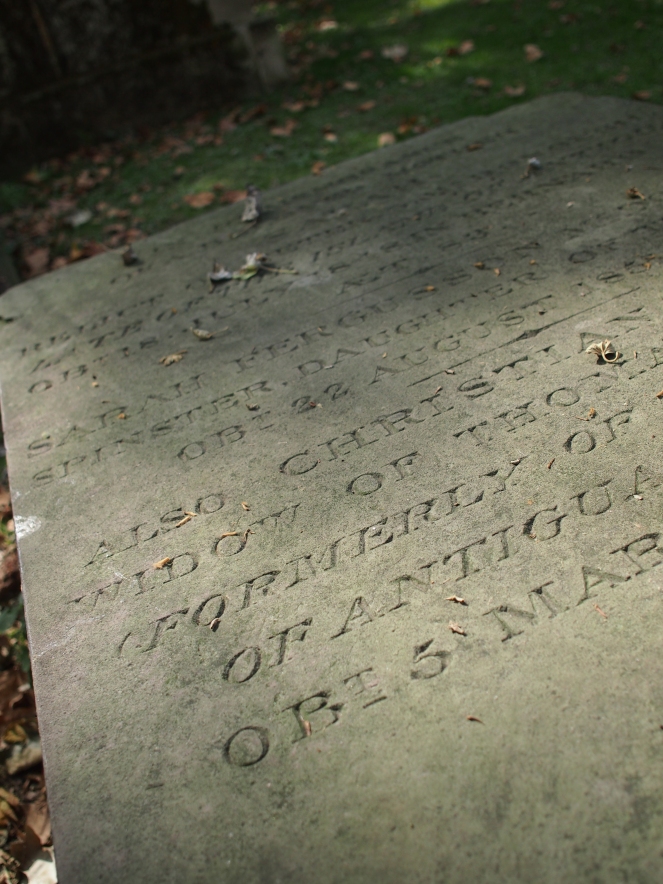

Another grave shows the links of some Bloomsbury residents with the Caribbean island of Antigua.

The closure of the burial ground in the 1850s was not the end of the story, but the beginning of a transformation. Mid-Victorian London was a desperately unhealthy place, dirty and sooty and crowded, and although the city’s great parks and garden squares provided some green space, it was not enough. Octavia Hill, most famous as one of the founders of the National Trust, was an early campaigner for the acquisition and transformation of disused burial grounds into pleasant parks and open spaces. She described these spaces as “outdoor sitting rooms” for the residents of London’s poorest and most overcrowded districts. Octavia’s sister Miranda founded the Kyrle Society in 1876, which raised the funds for the restoration of old burial grounds, and the twin burial grounds of St George in Bloomsbury were among the projects the Society took on.

After a period of clearing undergrowth, removing some memorials and general landscaping, St George’s Gardens was opened to the public in 1890 by Princess Louise. The gardens were designed by William Holmes, who added sweeping paths and landscaped the place to look like a proper Victorian park rather than a disused cemetery. Many of the grander memorials were retained, however, and can still be seen today. The boundary between the two burial grounds, once separated by a wall, is now marked with fragments of old headstones, as pictured below.

The striking terracotta statue of Euterpe, Ancient Greek muse of instrumental music, is a relatively recent addition to the garden. Created in 1898 by sculptor John Broad of Doulton of Lambeth, she originally adorned a pub on Tottenham Court Road called the Apollo and the Muses Tavern. When this pub was demolished in the 1960s, Euterpe was donated to St George’s Gardens.

By the 1990s, the park had seen better days and Camden Council embarked on a big restoration project, which was completed in 2001. The actual design of the gardens is very little changed from its original Victorian design. Today, the gardens are popular with local residents – I visited on a hot afternoon in September, and many people were relaxing on benches or on the grass. It is home to a lot of beautiful old graves, many still legible, and makes for a perfect spot to while away some time on a pleasant day.

St George’s Gardens are maintained by Camden Council, and can be visited every day during daylight hours.

References and further reading

Friends of St George’s Gardens – History http://www.friendsofstgeorgesgardens.org.uk/history.htm

St George’s Gardens – London Gardens Online http://www.londongardensonline.org.uk/gardens-online-record.asp?ID=CAM092

List Entry Summary – St George’s Gardens, Historic England https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1378733

John Holmes and Peter Williams – The Newgate Calendar http://www.exclassics.com/newgate/ng346.htm

Euterpe (I didn’t know that was her name) really looks at home here don’t you think?

LikeLike

She really does. I’m glad she found such a fitting new home after the pub on TCR was demolished.

LikeLike

Super post! I visited with Bradshaw, but didn’t get to grips with all the facts, as you have done. By the way, do you know the Scottish National Library has a rich resource of ordnance survey maps online? http://maps.nls.uk/os/

LikeLike

That archive of OS maps is *fantastic* – thanks for sending me the link!

LikeLike

Some how I missed this when it first was posted. As always, Caroline, I enjoy your research and your beautiful writing. My vicarious meanderings through London and other places with you is a joy. Your research and thoughtful comments make this a very special blog. Thanks and keep on posting. Bruce

LikeLike

Yes, these kinds of posts are almost as good as being there. Thank you for helping me explore vicariously.

LikeLike

Hi

I work nearby, and was aware that an artist living in Bloomsbury in the 1920s & 30s had done a wood engraving of St Georges in 1935. It’s clearly St Georges, but I’ve been all round the gardens and can’t see a similar monument with low railings and a tree in the same position. Perhaps it’s changed since then. The pic can be viewed here:

http://twowaystreet.herokuapp.com/things/PPA197160

LikeLike