One of the best-known Roman structures that still exists outside of Rome itself is the long defensive wall that snakes from the Solway Firth to Newcastle across the north of England: Hadrian’s Wall. Just south of the wall, in Northumberland, the remains of a Roman fort are being uncovered. Vindolanda’s story is ever-evolving: each summer a team of archaeologists and volunteers uncover more of the fort, discovering buried structures and artefacts that continue to enrich our knowledge of this amazing site. The most precious of all things found at Vindolanda – miraculously preserved due to the damp nature of much of the site – are the little wooden tablets with their written accounts of life on the Roman Empire’s northernmost frontier.

The settlement of Vindolanda was first occupied by the Romans many years before Hadrian’s Wall was built a mile or so to the north. The Roman invasion of the British Isles began on the south coast in AD43, and it’s thought that the first fort at Vindolanda was constructed about forty years later, in about AD85, as the Romans consolidated their control over the northern region of what is now England.

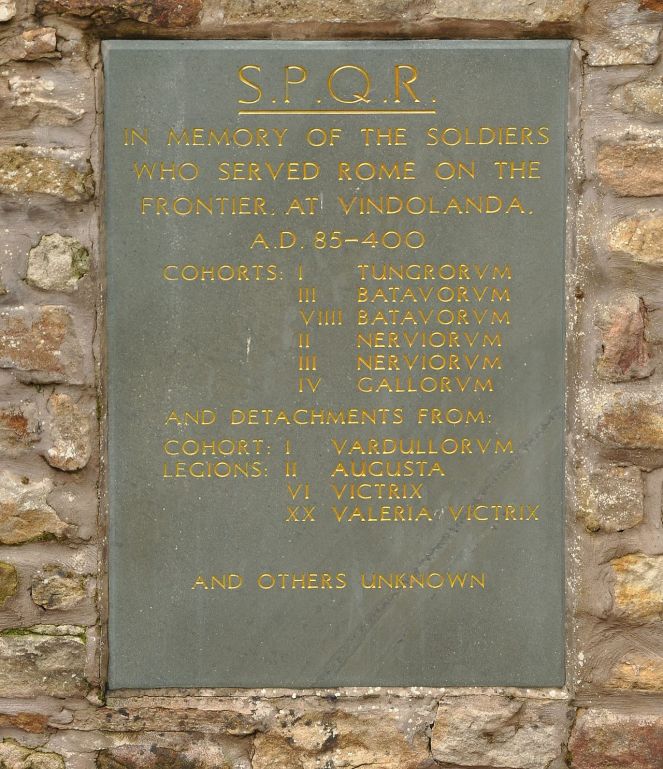

Vindolanda was not constantly occupied during the Roman period. Instead, forts were demolished and rebuilt according to the needs of the different cohorts occupying the site. At least nine different forts were built there. At times Vindolanda was a huge site, well-equipped with baths, luxurious quarters for its highest-ranked officers and supported by a civilian settlement outside the fort’s walls. At other times it was a smaller, less grand place, with wooden buildings nestled among the ruins of stone buildings. This makes the site incredibly complicated to visualise and interpret; thankfully written records have survived that fill in some of the gaps, giving us an insight into some of the different groups of soldiers and civilians who lived there over the centuries. A little memorial on the site remembers the people who spent time at Vindolanda – these men and their families would have come from all over the Roman Empire, and to many of those who came from warmer climes the Northumberland hills must have felt like a cold, wet and sometimes gloomy place to live.

The first fort at Vindolanda would have been constructed out of wood, allowing it to be built quickly from readily available materials. Some of the later incarnations of the fort may have been built wholly or partly out of wood too. Having gained control over the region that Vindolanda was a part of, Roman troops pushed further north into what is now Scotland, hoping to conquer the whole island. The fort at Vindolanda was located on the Stanegate, a Roman-built road that went from east to west, connecting the settlements of Carlisle and Corbridge.

The Romans encountered resistance from many different groups during their time as occupiers of Britannia. Most famously, the Iceni tribe from East Anglia, led by their queen Boudicca, rose up against the invading Romans and burned the settlements of Colchester, St Albans and London to the ground before their eventual defeat. Roman forces in Scotland also encountered fierce resistance from local people, so much so that after a few decades of attempts to establish settlements and Roman rule in Scotland, Roman troops were ordered to withdraw south, creating a defensible frontier just to the north of the Stanegate. The construction of Hadrian’s Wall began in about 122AD, the same year that the Emperor Hadrian visited Britannia. This defensive wall, which was around five to six metres tall, was further fortified with watchtowers, gates and defensive ditches, and served the dual purpose of protecting Roman settlements to the south and exercising control over trade and other comings and goings between communities north and south of the border.

The wet, sometimes even waterlogged ground at Vindolanda has caused the survival of some remarkable and incredibly rare documents – the Vindolanda Tablets. These thin pieces of wood, often folded down the middle, have notes, letters or lists written on them and their contents have given researchers an incredible level of insight into life at Vindolanda, including the resources consumed by those living there, and the inhabitants’ everyday lives. Because of the Vindolanda Tablets we even know the names of some of the people who lived at Vindolanda. The first of the tablets were discovered in 1973, and many more have been found since. Most of the tablets date from quite an early period of the area’s occupation – at the end of the 1st Century, a few decades before Hadrian’s Wall was built. The tablets were thrown away as rubbish into a heap or pit where the ground was waterlogged, ensuring their survival until they were uncovered by modern-day archaeologists.

The handwriting on the tablets – Roman cursive – is very different to the clear carved letters seen on many Roman monuments. Roman cursive is difficult to read and only a few specialists have the expertise to decipher it. Over 700 of the tablets found at Vindolanda have been transcribed and translated, although the fragmentary nature of many of the tablets can mean that only small sections of the original letters survive or are legible.

One of the most well-known of the Vindolanda tablets is a party invitation from Claudia Severa to Sulpicia Lepidina, whose husband was stationed at Vindolanda at the end of the 1st Century. It is thought that Claudia Severa and her family were based at a nearby fort. The letter is one of the earliest examples ever found of Latin written by a woman.

Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On 11 September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present. Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him their greetings. I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail. To Sulpicia Lepidina, wife of Cerialis, from Severa.

One tablet, written by a soldier, requests two pairs of sandals and some new underpants, while some of the more substantial documents discovered contain lists or inventories of different products: items include fish sauce, “Celtic” beer, oysters, barley, wine, bacon-lard, overcoats and tallow (animal fat used to make candles). One letter from a man selling grain and sinew requests payment for goods; another letter appears to list travel expenses.

Local people are rarely mentioned in the tablets; one exception is a tablet describing the fighting style of the Britons at a time when the Roman army was encountering resistance in the area:

… the Britons are unprotected by armour. There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons mount in order to throw javelins.

The Vindolanda Tablets are some of the most important archaeological finds ever discovered in Britain, and many of them are now on display both at the British Museum and at the museum at Vindolanda itself. For a long time they were the only such tablets to be found in Britain, but the recent excavations taking place at the River Walbrook, in the heart of the City of London, have also unearthed similar wooden tablets, and it is hoped that these wonderful artefacts will be able to give us an intimate glimpse into everyday life in Londinium in the way that the Vindolanda tablets have enriched our knowledge of life at a frontier fort.

The Vindolanda Tablets are a particularly rich and interesting source of evidence about life in this frontier fort, but many other objects and ruins have been uncovered at Vindolanda that shine a light on the people who once lived there: what they wore, what they ate, what tools they used, and so on. The remains of a bath house can be seen at the edge of the site, close to a steep hill, a tight cluster of pillars indicating where the building’s hypocaust (for heating water) was located. Evidence for the worship of many different gods has been found at Vindolanda, including the remains of what may have been a late-Roman Christian church and statues and shrines dedicated to gods from all over the empire, giving us an insight into the diverse origins of the people stationed at the fort.

One of the darkest discoveries made at Vindolanda is the skeleton of a child, uncovered within the ruins of the fort in 2010. Because Roman law and tradition did not permit the burial of human remains in built-up areas, the archaeologists who first uncovered the bones at first thought they might have belonged to a dog. In fact, the body was of a child whose gender was not able to be determined, who had been aged about ten at the time of their death and whose death was likely due to foul play, given the concealed and unconventional nature of the burial, and damage to the skull that may indicate a blow to the head. The child, nicknamed “Georgie” by the archaeologists who found the remains, was not born in Northumberland – analysis of teeth indicated that they had grown up in the Mediterranean. We will never know for sure who this child was, but they may have either been a slave or a member of a soldier’s family.

Some of the strangest ruins to be found at Vindolanda are a series of round buildings that have more in common with pre-Roman British roundhouses than any Roman structure. One possible interpretation of these buildings is that local farmers – native Britons who probably lived in roundhouses similar to those that their pre-Roman ancestors lived in – lived within the walls of the fort for a period, perhaps at a time when there was a lot of fighting in the area. It’s possible that these buildings date from a turbulent period in the early 3rd Century, when there was a rebellion in Britannia that was severe enough that the Emperor Septimus Severus came to the province in person with an army to regain control.

Vindolanda was no longer used as a fort after the Romans withdrew from Britannia at the beginning of the 5th Century, but at different times the site was still used as a settlement. The sturdy buildings on the site would have provided shelter, or materials for new buildings. Evidence of post-Roman burials have been found close to the fort, and stones from the fort were used to construct an early Christian church that was built inside the fort’s walls.

As Vindolanda is located in a remote area, far from any large towns or cities, the fort’s remains were less damaged or plundered than many other Roman settlements which were quickly robbed out by subsequent settlers for their building materials. This is why there has been so much for modern archaeologists to find. As late as the 18th Century, 1300 years after the Romans left, visitors to the site noted that the ruined bath house still had its roof, and many other features of the site that hadn’t been covered by mud or grass were still intact.

Antiquarians and archaeologists first began to dig and discover at Vindolanda in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Over the last sixty years the Birley family has played a huge part in excavations of Vindolanda and the sharing of knowledge about the site. Eric Birley, whose academic interests focused on Hadrian’s Wall, purchased the house close to the site of the fort at Vindolanda, and began to study the site more closely. Major excavations began in the 1960s and continue to the present day. Eric’s sons Robin and Anthony and grandson Andrew all remain closely associated with Vindolanda today, and the family home now houses the Vindolanda Museum, where artefacts found on the site and information about the fort’s history are presented to visitors.

The annual digs at Vindolanda attract archaeologists from all over the world. All kinds of people volunteer their time and skills – experienced professionals, students at the beginning of their careers and amateurs all work on the site for two weeks at a time. Places on the digs are snapped up as soon as they become available – the rich archaeology at Vindolanda is a powerful draw to those interested in the site. Visitors to the ruins can see the archaeologists in action over the summer months. The work is not for the faint-hearted or the unfit: the archaeologists toil in all weathers (although on particularly wet days they tend to spend time indoors cleaning newly-discovered finds), and on my most recent visit, in August 2016, it was a boiling hot day with very little shade.

Vindolanda is a wonderful site. The amazing volume of finds that have come out of the wet Northumberland soil has allowed archaeologists to paint a rich picture of life over four centuries at this Roman frontier fort, from descriptions of everyday life on the precious wooden tablets to pottery and coins and even the skeleton of a murdered child. The ruins can be visited from February to December each year, and there are two associated museums for visitors to enjoy too – the Vindolanda museum in the former home of the Birley family, and the nearby Roman Army Museum. This part of Northumberland is perfect for those interested in Roman history: as well as Vindolanda, a number of other Roman forts are close by, and one of the most picturesque stretches of Hadrian’s Wall can be found just to the north.

References and further reading

Roman Vindolanda Fort and Museum – Life at Vindolanda http://www.vindolanda.com/roman-vindolanda/life-at-vindolanda

Mike Ibeji – “Vindolanda,” BBC History, 16th November 2012 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/vindolanda_01.shtml

Vindolanda Tablets Online Database http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/4DLink2/4DACTION/WebRequestQuery

Child skeleton at Vindolanda fort ‘from Mediterranean,’ BBC News, 28th August 2012 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-tyne-19399441

Juliet Rix – ‘All Roads Lead to Vindolanda Fort,’ Daily Telegraph, 25th June 2010 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/wellbeing/outdoors/7850041/All-roads-lead-to-Vindolanda-Roman-Fort.html

I like the stones. Id like to use them to build a castle on higher ground. They dont look very well in ruins. Thanks for the photos. Bruce

LikeLike

Thanks for this post. We got to live in England for 5 years and Vindolanda was one of my favorite places to visit. You have made me want to go back and see all that has been discovered since all those years ago.

LikeLike

Hi, again Caroline Riveting display as always. I would like to add as a patron of your work on Flickering Lamps, that I have some questions. Is is their anyway to get in contact with you? Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, the best way to get in touch is via the contact form on this page – https://flickeringlamps.com/caroline/

LikeLike

There is a problem on the patreon page, when I tried to place the number of times per month it would not let me. I was going to include more times then the default which was 2. If you can repair that part I will upgrade. On a fun note I noticed someone named Caroline doing research on which craft on the http://sarahannelawless.com/. I was going to say hi but I wasn’t sure that it was you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve had a look at the Patreon FAQs and this page may be helpful for you – https://patreon.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/203913699-How-do-I-edit-my-pledge- The way that Flickering Lamps’ patreon is set up is that patrons are charged when a new article is published, rather than a monthly charge.

I’m afraid that wasn’t me on Sarah Anne’s blog!

LikeLike