Sheffield, in south Yorkshire, is famous around the world as a centre of steel production – stainless steel was invented in the city in 1912 and many thousands of the city’s residents worked in crucibles and factories producing steel and steel products such as cutlery and weapon components. On a peaceful hillside thousands of Sheffield’s citizens lie at rest, some with graves marked by grand memorials, others unseen beneath the trees and undergrowth. After a period of postwar neglect and uncertainty, the Sheffield General Cemetery is now a celebrated part of the city’s heritage.

The General Cemetery was opened in 1836 – the same year that West Norwood Cemetery was opened in London. Similar to the large cemeteries in London that have been explored on Flickering Lamps, the General Cemetery was opened in response to overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions in Sheffield’s churchyards. Sheffield’s population grew rapidly in the early decades of the 19th Century – from around 60,000 in 1801 to over 130,000 in 1841. There had been an outbreak of cholera in the city in 1832 and many of the hundreds who died in this epidemic were buried in a mass grave. Even without the added pressures of an epidemic, the local churchyards were struggling to cope with the city’s rising population and crypts and churchyards were becoming overcrowded and desperately unhealthy places. In response to this, a modern solution was proposed. The Sheffield Cemetery Company was set up in 1834 and land (a former quarry) was acquired on a hillside overlooking the centre of Sheffield, at a cost of £1,900.

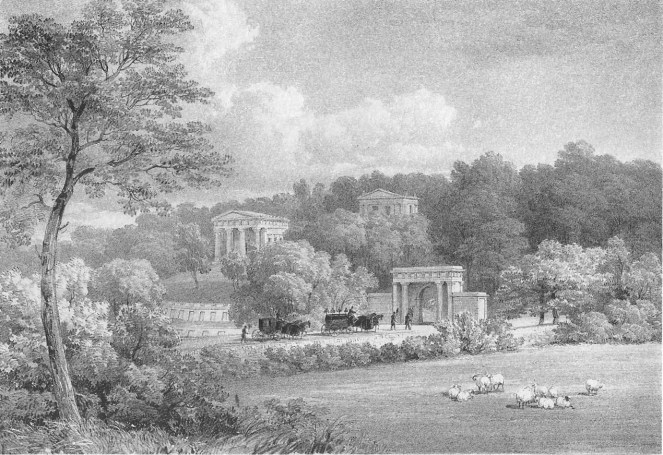

The cemetery was originally opened as a Nonconformist burial ground, and the cemetery company was a private, profit-making enterprise, not associated with any of the city’s churches. The General Cemetery’s nine acres were landscaped by Samuel Worth, creating an attractive environment with winding pathways, terraced catacombs and many specially-planted trees and plants – a pleasant place for the living as well as the dead. All of this was unusual in the 1830s – Sheffield General was one of the first landscaped, privately-run cemeteries to open outside of London.

The Nonconformist Chapel is probably the most well-known structure in the cemetery, and was completed before the cemetery opened in 1836. It is primarily Classical in design, although Egyptian influences can also be seen, particularly in the front doorway.

Egyptian features are also visible on the main gateways into the cemetery, in particular the Egyptian Gate situated at the top end of the cemetery. The top of the gateway features a winged sun, and each of the gates is decorated with an ouroboros – a snake biting its own tail, which is an ancient Egyptian symbol representing the infinite cycle of life and death.

The landscaping of the cemetery incorporated a number of mature trees that already existed on the site – early images of the cemetery and 19th Century maps indicate that a significant number of trees pre-dated the cemetery’s founding.

However, despite the site’s prominent location and beautiful landscaping, it took about six years for the first thousand burials to take place at the General Cemetery. By the end of 1839 just 499 burials had taken place there. Perhaps the cost of burial there was off-putting to some; others may have worried that its relatively isolated location might make it an easy target for bodysnatchers. No doubt other local families did not wish to bury their loved ones in a burial ground set aside for nonconformists, without the consecrated ground sought out by Catholics and Anglicans.

In 1850, an extension to the burial ground was consecrated for Anglican burials by the Archbishop of York. The Anglican and Nonconformist sections of the cemetery were divided by a wall, known as the Dissenters’ Wall. An Anglican chapel was completed in 1850, with a disproportionately large spire that was deliberately designed to be seen from far away. The chapel’s Gothic style is a little out of step with the rest of the cemetery’s architecture- this was perhaps a deliberate move. In the 19th Century, Gothic Revival architecture was closely associated with high church Anglican and Catholic churches and burials, whereas the Neoclassical style seen in the General Cemetery’s nonconformist chapel, and many of its prominent monuments, was associated more with nonconformist and more austere Anglican churches.

The hillside location of the General Cemetery put me in mind of Highgate, in London. The steep hillside is crisscrossed by curved paths leading into the trees. In keeping with the nonconformist nature of the cemetery’s oldest section, the monuments are less ostentatious than Highgate, but nonetheless they make for a striking sight in amongst the trees and ferns.

One of the most prominent memorials in the cemetery is that of William Parker, who died in 1837. Parker, whose father was a table-knife manufacturer, was a cutlery merchant. This article shows his name on a page of the cemetery’s burial records, with his cause of death listed as ‘apoplexy.’ A piece in the Sheffield Independent on 11th February 1837 reported that a large number of the city’s cutlers were set to take part in a procession to the cemetery on the day of William Parker’s funeral. The newspaper report then warmly paid tribute to William: “Mr Parker combined with uncommon talents for business, the strictest integrity and honour, and great urbanity. Nor was he forgetful to cultivate and exemplify those higher virtues which belong to the Christian.”

The untold story of Parker’s grave is the sad tale of his wife, Katherine. William Parker died intestate, meaning that he had no will – no binding agreement had been made about the distribution of his money, business interests and property after his death. Even today, dying intestate can be an administrative nightmare for the family of the deceased. Although according to the laws of the time Parker’s wife was not able to legally own property, it fell upon Katherine to manage her late husband’s affairs and oversee the winding up of his business. As well as this, Katherine was left to bring up the couple’s five children alone. Poor Katherine died by suicide in 1844, and the inquest into her death noted that she had had ‘immense anxieties and much to manage.’

Mark Firth was one of Sheffield’s prominent steel manufacturers and his family grave, topped with a carved urn and surrounded by red railings, is difficult to miss. With his father and brother, Firth was part of the Thomas Firth and Sons steel business, which began operating in 1842. As well as being part of the city’s steel manufacturing community, Mark Firth was also elected Master Cutler of the city in 1867, and – standing on the Liberal ticket – was elected Sheffield’s Mayor in 1874.

In common with many successful businessmen of the age, Firth used some of his wealth to benefit the city he lived and worked in. He donated the land that now makes up Firth Park, a public park in the city which was opened in 1875. He also founded Firth College, an arts and sciences institution, in 1879 – along with the Sheffield Medical School and Sheffield Technical School, Firth College went on to become the University of Sheffield in 1897.

Thomas Firth and Sons continued to operate after Mark Firth’s death, and in the 20th Century merged with a neighbouring steel company, John Brown and Company. The company born out of this merger, Firth Brown Steels, is still operating today – one of the oldest steel companies still existing in Britain. Most famously, the Brown-Firth Laboratories were the location where Harry Brearley invented stainless steel in 1912.

The 20th Century was a less prosperous time for the cemetery, in common with so many other grand Victorian cemeteries all over Britain. The site was beginning to fill up, and after the Second World War only a few burials were taking place each year, almost all of them in existing family graves. By this time, around 77,000 people had been laid to rest in the General Cemetery.

In 1979, the cemetery was closed to new burials. For a number of years the site’s future was uncertain – a large number of shares in the site had been sold to a development company in the 1960s, but the prospect of exhuming thousands of bodies in order to build housing on the site proved an insurmountable obstacle, and in time control of the site passed to Sheffield City Council. Around 800 headstones were cleared from the Anglican section of the cemetery and the area was laid out as a public park.

Some of the headstones moved at this time were set in the ground on the cemetery’s terraces.

Today, the General Cemetery is managed by a charity, the Sheffield General Cemetery Trust. As well as securing funding to restore the Nonconformist chapel, the Trust has been instrumental in promoting the cemetery as a nature habitat and an important source of information about Sheffield’s history. Public events and guided tours take place regularly. Information about upcoming history and nature events at the cemetery can be found here. Members of the Trust have also researched and published pamphlets on the history of the cemetery, highlighting the lives and deaths of many of those buried there. This article has barely scratched the surface in terms of the many illustrious and interesting figures who rest in the cemetery. After a few decades where the cemetery became overgrown and sad, threatened by redevelopment, the Sheffield General Cemetery has now found a prominent place in the celebration of Sheffield’s history and is a beautiful place to walk among the gravestones and discover the names and stories of many of Sheffield’s residents.

Sources and further reading

Sheffield General Cemetery Trust

She Lived Unknown: a celebration of women in the Sheffield General Cemetery, pamphlet produced by Sheffield General Cemetery Trust, 2013 revised edition

Sheffield General Cemetery – Historic England, List Summary

View From A Hill – an excellent resource for stories about individual graves and people buried in the General Cemetery

The newspaper reports quoted in the article were accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.

As a Fulham boy I find the Brompton pages Extremely interesting, looked up the Killmoory Mausoleum page, fascinating, thank you for the information and photos

LikeLike

Great recent post, great blog! Have you visited the Crossbones Remembrance Garden in Southwark? Just published a guest blog post about it, neat coincidence to find you here, actually more like a rediscovery, will certainly be “scooping” some of your posts to the Historical London section of my scoopit account. With full credits, of course!

LikeLike

When I first saw the “Steel City” bit of your title, I thought, “oh, a Pittsburgh post!” until I read on. Hadn’t realised Sheffield is called the Steel City too! At any rate, it’s a beautiful cemetery. I love the ouroboros detail on the gates!

LikeLike

Wonderful piece Caroline, if you let me know next time you are here I would be pleased to show you around! @churchdetective

LikeLike

I enjoyed this especially. One day I wish to take up residence in a cemetary such as Sheffield

General. Bruce

LikeLike