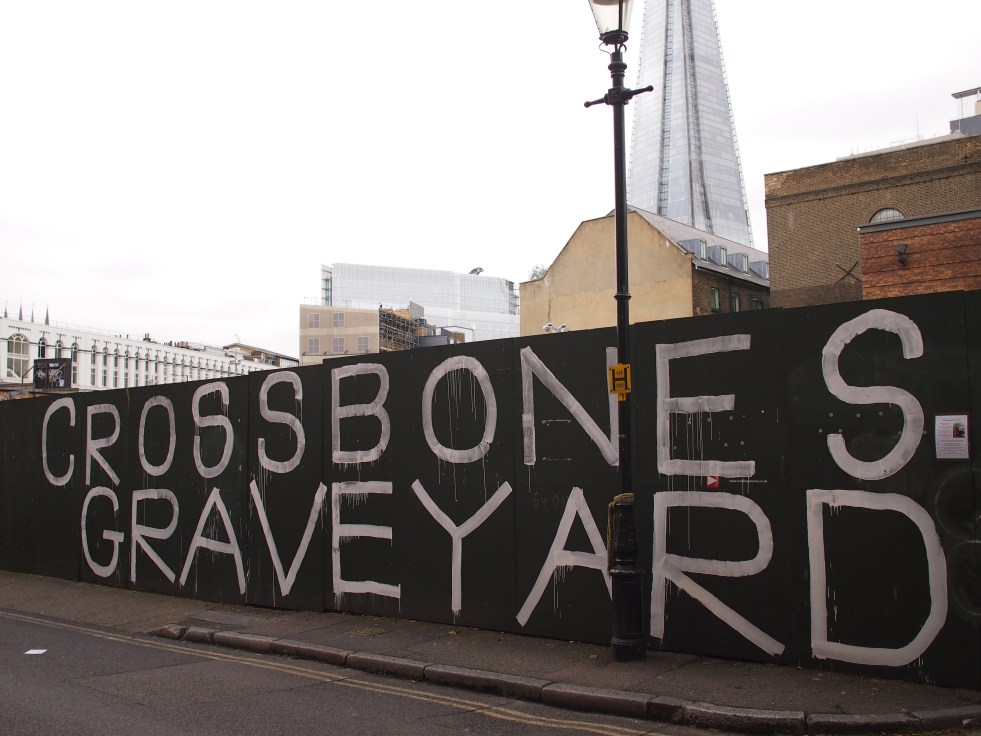

If you walk along Redcross Way, a quiet street a stone’s throw away from the hustle and bustle of London Bridge Station and Borough High Street, a strange sight can be found. Hundreds of colourful ribbons, flowers, toys and other trinkets are tied to the railings that surround a small garden, some bright and fresh, others faded with time and exposure to the elements. This is Cross Bones, an old burial ground where thousands of Londoners, mostly the poorest members of society, were laid to rest. In recent years this place has been transformed from a bare piece of land to a colourful community garden dedicated to the memory of London’s outcast dead.

Cross Bones is an old burial ground that falls within the parish of St Saviour and St Mary Overie, Southwark – better known today as Southwark Cathedral. For many years it was one of the burial grounds associated with the parish, until its closure in the 1850s. It is associated with the burial of Southwark’s poorest members of society, in particular the ‘Winchester Geese’, women who worked as prostitutes in the Liberty of the Clink. In recent years, the Winchester Goose has become a symbol of Cross Bones, as the site has been revived as a memorial to the poor souls interred within.

John Stow’s famous Survey of London, published in 1598, is the source of Cross Bones’ association with the burial of prostitutes, or ‘Winchester Geese.’ From the 12th Century, the Bishop of Winchester had a palace at Bankside, and within the area of his jurisdiction – the Liberty of the Clink – many activities that were illegal in the City of London, such as bear-baiting and prostitution, were permitted. In his Survey of London chapter that covers Southwark, Stow described some of the many rules that governed the ‘stews’ or brothels where these women worked in the Liberty of the Clink. These rules included “no stewholder to keepe any woman that hath the perilous infirmitie of burning,” “no single woman to take money to lie with any man, but shee lie with him all night till the morrow,” and “the Constables, Balife, and others every weeke to search every stewhouse.”

Although the Bishop of Winchester profited from the labours of these women in life, Stow described how the Church turned its back on them in death:

I have heard ancient men of good credite report, that these single women were forbidden the rightes of the Church, so long as they continued that sinnefull life, and were excluded from christian buriall, if they were not reconciled before their death. And therefore there was a plot of ground, called the single womans churchyeard, appoynted for them, far from the parish church.

Cross Bones has long been identified as this ‘single women’s churchyard’, but there is actually no concrete evidence that Stow’s ‘single woman’s churchyard’ and Cross Bones are the same place. It is unclear when Cross Bones was first used as a burial ground – it may well have started off as an unconsecrated poor ground. For centuries it was part of the lands owned in the area by the Bishop of Winchester, and it may be the case that the Bishop leased out this particular patch of land to be used as a burial ground. But in 1665, as the Great Plague ravaged London, the site was acquired by St Saviour’s parish. It may then have been used for plague burials, as the number of those dying may have been too great to be managed by the churchyard immediately adjacent to St Saviour’s church.

After the outbreak of plague was over, Cross Bones continued to be used as a burial ground for St Saviour’s parish – as illustrated in John Rocque’s map below. Its location in a poor, overcrowded part of the parish, and its distance from the main parish church, meant that it was probably largely used as a poor ground, for the burial of the parish’s paupers and others with few means. It is estimated that at least 15,000 people were laid to rest there over the years.

In the early 19th Century, part of the burial ground was covered over when a school was built, restricting the amount of space that could be used for burials. However, the population of Southwark, like that of the rest of London, was growing and Cross Bones’ location in a poor part of town meant that there was no shortage of the dead requiring burial. The remaining section of the burial ground continued to be used, and became horribly overcrowded. Despite a number of attempts to get the graveyard closed, burials continued until 1853, when Cross Bones – “completely overcharged with dead” – was finally closed for good.

The site lay derelict for many years, briefly hosting a fairground that raised the ire of locals with its noise and crowds. It was also used for a time as a builder’s yard. In 1883, Cross Bones was offered to developers as a building site. Lord Brabazon, chairman of the Metropolitan Public Garden, Boulevard, and Playground Association, wrote a letter entitled ‘The Use and Abuse of Disused Burial Grounds in the Metropolis’ which was published in the Times on 10th November 1883. In this letter, he highlights the case of Cross Bones:

This ground is now being offered to the public, on lease, as an “eligible building site.” It is with a view to save this ground from such desecration, and to retain it as an open space for the use and enjoyment of the people, that I now address you.

Brabazon’s letter seemed to have the desired effect – the land was withdrawn from sale, and the following year the Disused Burial Grounds Act (1884) was passed, which prohibited the erection of new buildings on former burial grounds. However, Lord Brabazon’s hope that Cross Bones might be turned into a public garden – the eventual fate of many disused burial grounds in London – was scuppered, and Cross Bones instead continued to be used as a timber yard. In 1896, Isabella Holmes described it as “vacant, waiting for someone to purchase it as a playground.”

In the early 1990s, work began on extending the London Underground’s Jubilee Line south of the river, and as part of these works, an electrical substation needed to be built at Cross Bones. Before work on the substation commenced, an archaeological survey of the site was carried out. Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) excavated 148 skeletons, all dating from the later years of the cemetery – about 1800-1853 – from a small section of the site. It was estimated that this represented less than 1 per cent of the people thought to be buried at the site, but nonetheless MOLA were able to find out a lot about the graveyard’s occupants from these bones.

Around a third of the burials excavated were of perinatal individuals – babies who were stillborn or died shortly after birth. A significant number of children under five were also found, suggesting that the area suffered from a high level of infant mortality. A number of bones demonstrated that some of those buried at Cross Bones had suffered from scurvy or rickets, both conditions that can be caused by a poor diet or malnutrition. In addition, lesions found on other bones indicated the presence of syphilis, and overall around 60% of the individuals excavated showed signs of an infection of some sort. MOLA concluded that the bones they excavated represented “a post-medieval population from an area with a very poor socio-economic environment.”

One of the skeletons uncovered at Cross Bones was featured in the BBC television programme History Cold Case in 2010. The bones were of a young woman, probably in her late teens, who was only 4’7″ tall. Lesions on her skull indicated that she had suffered from advanced syphilis, meaning that she was probably infected with the disease when she was a child. An abhorrent belief was held by many men in the 19th Century, that if they had sex with a virgin, their syphilis would be cured. Tragically, all that this achieved was the abuse of young girls, generally from the poorest parts of town, who then also became infected with syphilis. The young woman featured in History Cold Case may well have been one of these victims. Analysis of her bones indicated that her diet had been poor – which perhaps accounted for her unusually short stature – and high mercury levels found in the bones indicated that she had had some treatment for syphilis. Until the discovery of penicillin, mercury was often the only treatment option for syphilis. The Cross Bones woman, poor as she likely was, may have accessed this treatment at a charity hospital. Mercury treatment had terrible side-effects, and many syphilis suffers are thought to have died from mercury poisoning rather than the syphilis itself. Who knows how many other who lie at Cross Bones suffered a similar fate to the woman featured on History Cold Case.

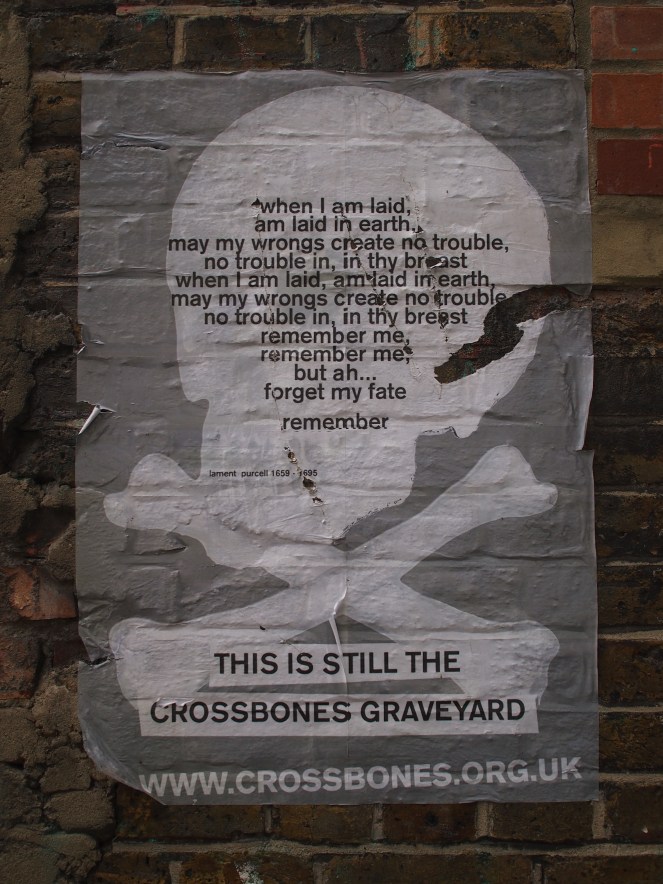

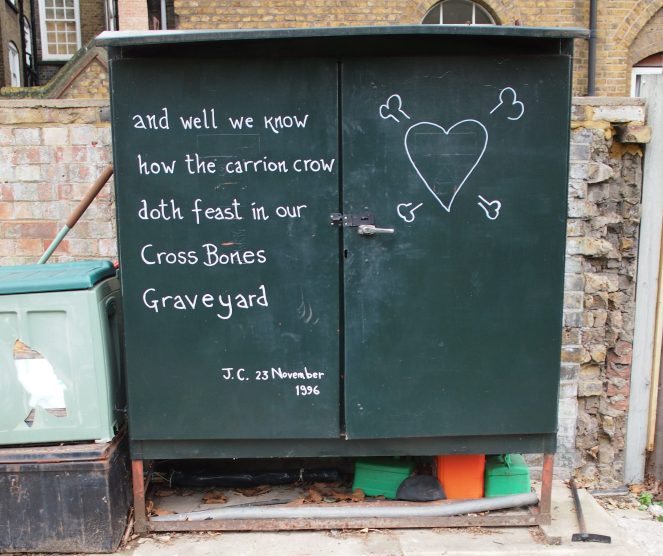

In 1996, John Constable – a Southwark-based playwright, poet and historian – began work on the series of poems and plays that would become The Southwark Mysteries. Central to the Southwark Mysteries is the figure of the Winchester Goose, who first appeared to Constable in a vision in November 1996, before he was aware of the existence of Cross Bones. Developing the story of the Goose inspired Constable to delve into the history of Cross Bones and through his research and activism he became the driving force behind the campaign to promote the story of Cross Bones and transform the site into a community space and a memorial to London’s outcast dead.

The Southwark Mysteries, a cycle of poems and plays in the style of medieval mystery plays, was first performed in 2000 at Shakespeare’s Globe and Southwark Cathedral, and tells the story of Southwark’s history through the eyes of the area’s outsiders and outcasts, including the Winchester Geese of the Liberty of the Clink. Parts of the Mysteries have been performed at Cross Bones itself, and on the 23rd of each month, Constable leads a vigil to London’s outcast dead at Cross Bones, by the wall of ribbons.

After many years of campaigning, Cross Bones finally opened to the public in 2015 as a community garden, after securing a short lease from Transport for London, which owns the land. The site is now managed by the Bankside Open Spaces Trust, and a team of volunteers helps to maintain and supervise the site. A sign by the gate lets passers-by know when the garden is open to the public (opening times vary). A covered walkway welcomes the visitor into the space, and its flowerbeds are decorated with oyster shells, typical fare of London’s poor in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

The concrete that has covered the burial ground has been broken up in places, and incorporated into the landscaping, accompanied by trinkets, statues and other objects left by well-wishers.

Thanks to its modern transformation and status as the inspiration for the Southwark Mysteries, Cross Bones surely rates as one of London’s most unusual former burial grounds. Its colourful decorations and commitment to remembering the poor and the outcasts draw visitors from all over the world – on the afternoon that I visited to take the photographs for this article, some Australian tourists were among those who had taken the time to visit. The myths and legends that have endured about Cross Bones give it a rare mystique that continues to draw interest, but most of all it serves as a poignant reminder that a huge proportion of Londoners never had a grand grave marked by a fancy headstone, but disappeared instead into unmarked paupers’ graves.

Cross Bones is one of the stops on “Southwark’s Lost Burial Grounds,” the guided tour I carry out on behalf of Southwark Cathedral. Please check the Events page for any scheduled tour dates and ticket information.

References and further reading

John Constable – The Southwark Mysteries, Oberon Books, London, 1999

John Stow – Survey of London, 1598

Cross Bones Burial Ground summary – Museum of London

Paul Slade – Crossbones Girl

Riveting reading. I wish I could get up to London for your talk!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, as always, Caroline for an insightful, beautifully written and well researched blog post. Sorry I can’t join you for your walk and tour. I’m sure it will be wonderful. For now, I journey with you here. Bruce

LikeLiked by 1 person

i don’t know if you will see this because I have WordPress ‘issues’ at the mo. But yes it is a really interesting place. I used to walk past it walking between City hall and the old LDA. When / where is your talk?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing this. It’s uplifting to see London’s outcast dead finally being acknowledged. I’d have loved to to see the mystery plays enacted at Crossbones. I’ve added ‘The Southwark Mysteries’ to my ‘list’.

LikeLike

Thanks for such an informative post I have visited this forgotten little place over the years and its transformation now is remarkable it’s a lovely little memorial space

LikeLike

A great post – I’ve often been past the site and the gates but hadn’t realised that it was open to the public. A tribute to everyone that it hasn’t been built on.

LikeLike

The last time I visited you couldn’t get further than the gate so I’m glad you posted photos of what it looks like inside now. I used it as inspiration for a ghost story so I’m pleased it’s been saved.

LikeLike