West Norwood, which opened as the South Metropolitan Cemetery in 1837, is one of London’s most spectacular cemeteries, its grand tombs and monuments laid out along landscaped paths and mature trees. Of the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries that opened on London’s outskirts in the early Victorian period, West Norwood was arguably the most sought-after of them all as a burial place, with its beautiful location on a south London hillside. The wealth of many of those interred there is reflected by the beautiful memorials raised in their memory.

We’ve already visited the Greek Orthodox enclave within West Norwood, but now it’s time to explore the rest of the cemetery and the plethora of historic and interesting graves that can be found there.

West Norwood was, from the start, designed to be a Gothic Revival cemetery. In the early decades of the 19th Century, the Gothic Revival movement gained pace and went on to be the influence behind some of the Victorian period’s most iconic buildings. Architects took inspiration from Europe’s medieval Gothic structures, incorporating the decorative features of these magnificent structures into modern buildings, both religious and secular. The Gothic Revival was arguably also a reaction against the rapid industrialization taking place in this period, an architectural style looking back on a romantic past rather than the polluted, crowded present day. Gothic Revival architecture is characterised by pointed arches, steep spires and decorative tracery, with some Gothic Revival funerary monuments looking almost like miniature buildings.

West Norwood Cemetery was designed by the illustrious architect Sir William Tite, whose best-known London building is the Royal Exchange in the City of London. Tite – who was buried at West Norwood after his death in 1873 – was a director of the cemetery company, and oversaw the landscaping and architectural direction of the new cemetery. Unlike Brompton, which is laid out like a grid, emulating the shape and layout of a cathedral, West Norwood’s landscape is characterised by sweeping, curving pathways and gentle slopes.

When the cemetery was first opened, it was dominated by two Gothic Revival chapels, one for Anglican funeral services and the other for Nonconformist services – a common arrangement in 19th Century cemeteries. Neither of these chapels survive today: the Nonconformist chapel was destroyed by a V1 rocket attack during the Second World War, and the Anglican chapel was demolished in the 1950s.

Today, a single chapel hosts all services held at the cemetery – a modern structure built alongside the crematorium. The chapel was constructed in the 1960s, but continues the cemetery’s Gothic Revival theme – the picture above shows its pointed windows and doorways. Even the crematorium’s chimney has Gothic features in its brickwork decoration. The occasional burial still takes place at West Norwood, in existing family graves, and the chapel and crematorium are used regularly for funeral services and cremations. A funeral took place there on the day I visited the cemetery to take photographs for this article – fortunately I’d got round to looking at the monuments closest to the crematorium long before any mourners arrived, and was able to give the crematorium a wide berth while the funeral service was going on. Giving mourners space and privacy is, to me, the most important thing to remember when exploring an old cemetery – as a historian my reason for visiting these places is to discover their art, architecture and stories, but their primary purpose is as a place where the dead are buried and where people come to mourn.

A crematorium has existed at West Norwood since 1915, although the original building was destroyed along with the Nonconformist chapel during the Second World War. Although cremation has been practiced by humans for millennia, it only became legal in the United Kingdom in the 1885, with the first crematorium being set up in Woking in the early 1880s. In the years running up to the First World War, cremation began to grow in popularity and it was in response to this that West Norwood’s crematorium was opened in 1915. A very early example of a cremation burial can be found at West Norwood – presumably H W Lindow, who died in 1887 and whose grave is fittingly marked by an urn topped with flames, was cremated at Woking (the only crematorium available at the time) and his ashes brought to West Norwood for burial.

That there are any Victorian graves left for us to see today is something of a relief, because when Lambeth Council took over the running of West Norwood in 1965 (after the cemetery company that had run it since it opened went bust), the council cleared large areas of monuments and began to reuse old graves for new burials. The Friends of West Norwood Cemetery, set up in 1989, challenged this activity in 1993 and the resue of old graves ceased. However, by this time it is estimated that around forty per cent of the cemetery’s memorials had been removed or damaged.

It is for this reason that old and new graves are all mixed up together, stately Victorian headstones alongside memorials from the 1980s and 1990s.

When it first opened, West Norwood also offered catacombs, located beneath the Anglican chapel, as an alternative to being buried in the ground. Although the Anglican chapel is now long gone, the catacombs are still there: a makeshift-looking structure now covers the site of the catacombs to protect them from the elements. It is occasionally possible to visit the catacombs, to walk among the lead coffins and see the hydraulic lift used to transfer coffins from ground level into the catacombs, but for the most part they are inaccessible for safety reasons. You can see pictures of the catacombs taken during previous tours here and here.

As London’s overcrowded churchyards began to close after new laws were passed in the 1850s, some churches purchased sections of the spacious new cemeteries. St Mary-at-Hill, one of the City of London’s many churches, purchased a plot of land at West Norwood in 1847 and carefully relocated the occupants of its little churchyard to West Norwood. The church’s crypt was cleared at the end of the nineteenth century, with these bones also given new burials at West Norwood. Over 3,000 of St Mary-at-Hill’s parishioners of the past now lie at rest at West Norwood, although the plot purchased by the parish was one of the areas affected by the actions of Lambeth Council in the early 1990s and now contains some newer burials too.

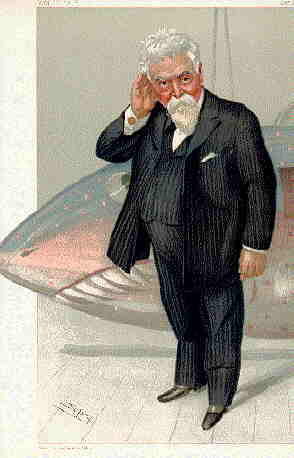

Sir Hiram Maxim, whose bold gravestone stands alongside a far more ornate memorial, was an American-born inventor who came to live in London in the 1880s, eventually becoming a naturalised British citizen in 1900. The years before Maxim left America for England were dogged with strife; his brother Hudson – also an engineer and inventor – had found more success in America and the brothers quarrelled over ownership of a patent for smokeless powder. Hiram had also been accused of bigamy by a woman who claimed he had married her whilst still legally married to his first wife, Jane Budden. He arrived in England with his second wife, Sarah Hayes – it is unclear whether a divorce with Jane ever took place.

Maxim’s most famous invention was the Maxim gun, the prototype of which was unveiled in 1884. This gun, the first portable, fully automatic machine gun, was widely used by British imperial forces in colonial wars until 1914, and was also widely used by other regimes around the world. Maxim’s inventions went far beyond the military – he filed patents for (among many other things) an automatic mousetrap and the first ever automatic fire sprinker. He also worked on various flying machines, none of which were successful. Towards the end of his life, Maxim invented a steam inhaler that helped to ease his chronic bronchitis. This particular invention was criticised by those who thought it quackery, but Maxim defended his work, saying “it will be seen that it is a very creditable thing to invent a killing machine, and nothing less than a disgrace to invent an apparatus to prevent human suffering.” Maxim died in 1916 – he was an atheist, and this may have influenced the austere design of his gravestone, devoid of any religious symbolism.

West Norwood continues to be a place of pilgrimage for admirers of a famous London preacher, Charles Spurgeon, who rests beneath an impressive monument at the heart of the cemetery. Spurgeon was pastor at the New Park Street Chapel in Southwark, and so many people came to listen to his sermons that a larger chapel at Elephant and Castle, the Metropolitan Tabernacle, was opened in 1861, and Spurgeon continued as pastor until his death in 1892. His popular sermons were often transcribed, and many of Spurgeon’s sermons and other writings were published and translated into other languages.

A chest tomb in one of the more overgrown sections of the cemetery is not decorated with Gothic motifs, but instead is topped with a stone ship (which has now sadly lost its mast) and features unusual and dramatic maritime bas-reliefs. This memorial marks the resting place of Captain John Wimble and his wife Mary Ann. John Wimble had a long maritime career, working on ships contracted by the East India Company to carry tea between India and England. Some of ships Wimble took charge of during his career are featured on his grave, the Florentia on the south side of the tomb, the London on the west side, and the Maidstone on the east side. The carving of the Florentia is particularly dramatic, showing the ship in stormy weather, perhaps an allusion to Captain Wimble’s ‘eventful life’ as described on his epitaph. His wife Mary Ann accompanied him on some of his many voyages, sharing in some of his adventures.

If John Wimble had had his way, this beautiful memorial would not be here for us to see today. He left instruction: “I direct that my body may be decently and plainly interred at the discretion of my beloved wife. She alone shall have the ordering and regulation.” Fortunately for those of us who enjoy learning about the lives of those who came before us, Wimble’s wife did not commission a plain memorial for her husband, but instead chose to mark his interesting life with a fitting and unique memorial.

West Norwood’s two ‘terracotta’ mausolea stand out against the grey and white of the cemetery’s other memorials. Both of these mausolea mark the burial places of illustrious individuals. The first is the mausoleum of Sir Henry Doulton and his family. Henry Doulton was born into a family of pottery manufacturers, and as an adult became a part of the family business, developing enamel glazes that helped Doulton become a market leader in the manufacturing of sanitary appliances and pipes. Doulton also supported the employment of male and female artists, developing a relationship with the Lambeth School of Arts, and fittingly his tomb is decorated with bricks and tiles from the Doulton Works.

The other terracotta tomb at West Norwood also has a prominent link to the world of art. Henry Tate was a successful sugar merchant, the first manufacturer of sugar cubes, and he used his vast fortune to contribute to a number of philanthropic causes. He gave money to hospitals, schools, and libraries, but his most famous foundation is the the National Gallery of British Art , now known as Tate Britain, at Millbank, London, constructed to house paintings by British artists that he had donated to the nation.

The illustrious figures and their graves that have featured in this article are only a small number of the famous residents of West Norwood. Among other famous names laid to rest here are Isabella Beeton, author of the famous Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, the architect Thomas Cubitt, and William Marsden, founder of the Royal Marsden Hospital.

The work of the Friends of West Norwood Cemetery has brought this beautiful and fascinating place back into the spotlight – FOWNC’s regular newsletters contain stories and research about the many inhabitants of the cemetery, and the Friends also work to raise money to restore monuments that have fallen into disrepair. After many years of neglect after the Second World War, London’s most prestigious Victorian cemetery is once again finding its rightful place showcasing and celebrating the lives and memories of the thousands of Londoners buried there.

I will be leading a guided tour of West Norwood Cemetery on 12th October 2019, as part of the London Month of the Dead. Tickets and further information can be found on the Events page.

References and further reading

Friends of West Norwood Cemetery

Tomb of Captain John Wimble, List Entry, Historic England

“John Wimble (1797-1851) – a life at sea,” Friends of West Norwood Cemetery Newsletter 69, September 2010 (PDF)

“100 years of Maxim’s ‘killing machine’“, New York Times, 26th November 1985

Wonderful photographs. I really must visit since many of my Talbot ancestors from Rotherhithe were buried there.

LikeLike

Excellent. Thank you.

LikeLike

Graveyards are sad places and often create pychological deppression. Many believe or like to believe that a grave burial is some kind of guarantee of an afterlife but I think it is a waste of space and time and all deaths must be cremated and disposed of in a remote location. Religions especially christianity leads people into delusional fantasies of which there is no basis of reality particularly regarding life after death and taxation not neccessarily in that order. Sure life after death looks absolutely terrific after taxes get it all out of everybody. This is my personal deduction from realistic observations.

Have a fine day. Bruce

LikeLike

I had a fascinating day in West Norwood Cemetery. I started off looking for ancestors who are buried there but then encountered a Friend of the Cemetery who was very helpful, and kindly sent me photos from the vaults of another ancestor’s burial place. A most memorable and interesting day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Caroline, I just wanted to let you know that I was recently nominated for the Blogger Recognition Award by a person who follows my blog, and in turn I was encouraged to nominate others whom I feel worthy. I don’t read many blogs, but your blog is one that I do read. I always enjoy learning about the places you visit the and seeing the photos you share. You can read about your nomination and see what I wrote about your blog.. So, congratulations! You can view you nomination at https://bappel2014.wordpress.com/2017/09/26/a-blogger-recognition-award-for-bruce/

Perhaps you’d enjoy some of the other blogs I nominated.

LikeLike

What is it about cemeteries? The stories, I guess; so many stories. I have heard so much about West Norwood Cemetery and could kick myself for not paying a visit when I worked nearby. Nicely written, informative and photographed.

LikeLike

Always very interesting, the research you manage adds to the feature

All good, thank you.

LikeLike

Fascinating post, really enjoyed it, and the photos are wonderful! 😀

LikeLike