One of the joys of graveyard exploration is the discovery of unusual graves and memorials – those with eccentric designs or strange stories attached to them. The imposing monument we’re looking at today, which towers above its neighbours in a pretty churchyard in the suburb of Pinner, definitely ranks as one of the strangest in Greater London – both for its design, and for the stories told about it.

It’s a long time since I was in Pinner – at least twenty years. When I was a child, my family stayed here a couple of times, and my first experience of the London Underground was the Metropolitan Line train rattling along its long route from Pinner towards the middle of London. Pinner’s centre is full of historic buildings – many of those on the high street were built in the 16th Century, and this history is celebrated with many plaques and signs informing the visitor of the great age of these buildings.

In the early 20th Century, the rapid growth of what became known as Metroland – vast suburbs that were constructed along the newly-built suburban rail and tube routes such as the Metropolitan Line – swallowed up the village of Pinner and surrounded it with smart, spacious new homes for those commuting into central London. Despite this development, the heart of Pinner still retains a village-like feel, and despite the presence of ubiquitous chains such as Starbucks and Zizzi on the high street, it doesn’t really feel like you’re in Greater London at all.

At the top of the High Street is the parish church, dedicated St John the Baptist. It has been here since 1321, though much of its present-day fabric dates from a 19th Century refurbishment. The churchyard surrounding it is neat and well-kept, with a sparse scattering of headstones largely dating from the 18th Century.

But the visitor to this churchyard cannot miss the anomaly among all of this tidy convention. A pyramid-like structure, built of brick and encased in stucco blocks, with a hollow base revealed by a metal grille, topped with a family crest of a double-headed eagle, and – strangest of all – with both ends of a stone coffin sticking out of the middle. It’s nothing like any of the other modest and conventional monuments that surround it in the churchyard, nor is it quite like anything else to be found in any of London’s many burial grounds.

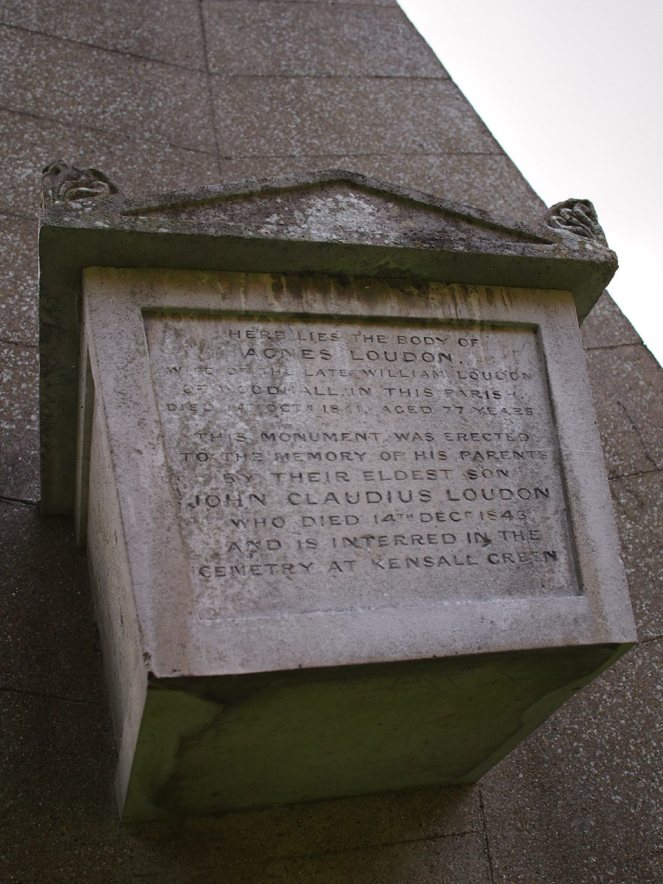

This imposing and eccentric monument marks the resting place of William and Agnes Loudon, who lived locally in a dwelling called Wood Hall. William Loudon died in 1809, while Agnes, his widow, died in 1841. I was not able to find a definitive construction date for the memorial – Historic England’s record of the monument states that it dates from 1843, while other sources mention 1809 as a possible construction date.

The strangeness of this monument is matched by the odd legend that has clung to it for many years, a story passed down through generations of Pinner residents and regularly picked up by the media. An article in the Harrow Observer published on 9th September 1921 states that

Legends die slowly, and if there is one more than another which refuses to be decently interred it is that associated with the stone coffin which is suspended in Pinner churchyard. Residents still believe that some mystery is attached to it; visitors make it an object of attentive pilgrimage and awe; picture postcards of the ‘gruesome’ monument used to be sold in the village.

The story goes that the Loudons were not buried beneath the ground, but within the great stone coffin that ‘floats’ in the middle of the monument. The reason given for this was that the Loudon family had been given the tenancy of a dwelling, but it was only theirs while William remained ‘above the ground’ – in other words, alive.

The tale continues: that the wording of the legacy the Loudon family benefitted them was taken literally, and that William Loudon was buried ‘above the ground’ to avoid triggering the clause that would cause their family to lose use of the dwelling bequeathed to them. (Incidentally, this gives strength to the argument that the monument dates from 1809, not 1843.) It is this supposed burial above the ground, in the strange ‘floating’ coffin, that gives this monument a mysteriousness that has captured imaginations ever since the monument was first built. Various 19th and early 20th Century newspaper and magazine articles about the Loudon monument emphasise this rumour of a very odd burial – the number of sensational stories are matched only by letters from various vicars of the parish refuting the claims and insisting that both William and Agnes Loudon were buried in a vault beneath the ground.

An alternative theory to that of the Loudons’ bodies being buried above the ground is that the monument symbolises height in some way. It could be interpreted as a symbol of piety, its tall form pointing towards heaven. This is backed up by a translation of the Latin inscription on one side of the stone coffin which states ‘This monument set up by John Claudius Loudon, the eldest of [William’s] sons, stands as a witness of his piety.’ The cryptic phrase incorporated into the design of the metal grilles at the base of the monument, ‘I byde my time’, may be a reference to family members anticipating being reunited in heaven.

The monument’s size and grandeur, however, could also have had a much more earthly intention – a way of boosting the Loudons’ profile in the local area. William and Agnes Loudon were not natives of Pinner, but moved there in the early years of the 19th Century, to a farm called Wood Hall. They joined their son John, who had been convalescing in Pinner after a bad bout of rheumatic fever. At Wood Hall, William and John sought to demonstrate a ‘Scotch’ approach to farming methods, layouts and buildings, but as William died in 1809, not long after the farmhouse was rebuilt, it is unclear whether this ever happened. Agnes continued to live at Wood Hall until her death in 1841. The reconstruction of the farmhouse at Wood Hall suggests that the Loudons had some degree of wealth, and as outsiders coming to Pinner later in life perhaps the intention of their monument’s grand scale and odd design was indeed to project their wealth and importance. Perhaps the monument’s triangular shape was inspired by the pyramids of Ancient Egypt.

The designer of this curious memorial – the eldest son of William and Agnes Loudon – was a man who had an interesting career, and is someone whose work I’ve come across many times whilst researching historic cemeteries. John Claudius Loudon was an early supporter of the garden cemetery movement in 19th Century Britain, and designed a number of cemeteries himself as well as writing extensively about his theories of cemetery design. Born in Lanarkshire in 1783, Loudon developed an interest in horticulture and landscape design at a young age and his father made arrangements for him to be apprenticed to a nurseryman and to receive tuition in botany at the University of Edinburgh.

Loudon’s work was highly influential – he was interested in agriculture, horticulture and the design of public spaces in both urban and rural settings. He was a vocal advocate for the provision of green spaces in Britain’s growing towns and cities, and created the ‘gardenesque’ approach to landscape design, which focused on the display of individual plants and trees. He is credited with the first use of the term ‘arboretum’ to describe a collection of trees planted for scientific study. Loudon was a prolific author during his lifetime, with his most famous work being the epic Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum, which was published in monthly installments between 1835 and 1838.

It was while working as a magazine editor that Loudon sought out the anonymous author of a science fiction novel, The Mummy! Or A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century. Published in three volumes in 1827, this novel told the tale of the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Cheops being reanimated in a futuristic 22nd-Century Britain. Loudon was particularly impressed and intrigued by the author’s portrayal of the future, and of the inventions contained in the story. The creator of this book was Jane Webb, who had published the novel as a means to support herself after her father’s death. When Jane and Loudon met the pair discovered a mutual love of botany and horticulture. They were married in 1830, and had a daughter, Agnes. Jane continued writing after their marriage, and wrote a number of books about horticulture, helping to make the subject more accessible and popularise it as a pastime among women.

Both John and Jane were great advocates for the improvement of green spaces within London – John’s first published work highlighted the importance of public squares as ‘breathing spaces’ within the city, and the blue plaque that marks their former home in Bayswater makes reference to the couple’s work in this area.

Loudon also took an interest in the design of cemeteries. In the early 19th Century the move from overcrowded churchyards to spacious, specially-designed suburban or rural cemeteries was gathering pace, and Loudon had many ideas, principles and designs to contribute to this movement. He had travelled through Europe in 1813, witnessing the often horrifying aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, experiences which seem to have proved formative in many of his views on cemetery design and burial practices.

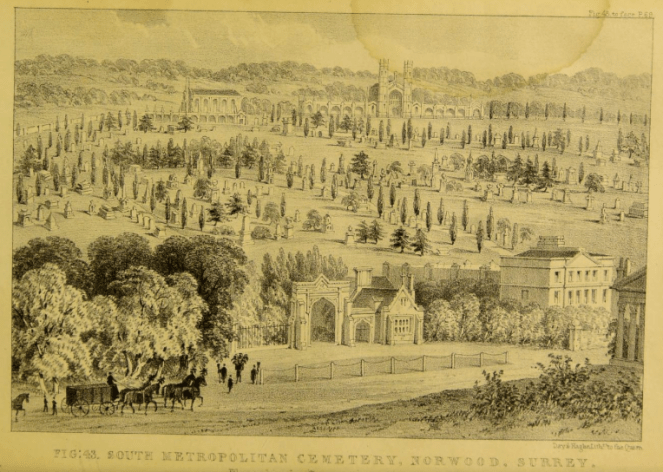

In 1843 he published a book called On the Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries, In this book he approaches cemetery design from the perspective of a landscape gardener, making use of his practical knowledge of horticulture. He was highly critical of the ways that trees and plants were utilised in many new cemeteries, singling out West Norwood‘s ‘clumps’ of trees for particular criticism. Loudon instead advocated the planting of single trees in a more spaced-out fashion, allowing for a better flow of air through the cemetery and reducing the large shadowy areas created by trees planted closely together. This is just one example of Loudon’s grounded and practical approach to cemetery design – something James Stevens Curl describes as ‘moral, hygienic and essentially utilitarian.’

Loudon made very clear his distaste for burying people in catacombs and considered many burial practices employed in the early 19th Century, such as the burial of several coffins together in a single grave without any space between them, as hazardous to the living. He described the practice of having coffins exposed to view in catacombs as ‘disgusting’ and instead recommended that coffins interred in vaults, catacombs and brick-lined be covered by soil or cement to prevent the escape of noxious gases that formed during the process of decomposition. It is this distaste for ‘unnatural’ forms of burial that is perhaps the most conclusive argument against the Loudon monument’s stone coffin actually containing a body.

Loudon was afflicted by health problems throughout his adult life, including the loss of his right arm after a botched operation that had been intended to help treat chronic arthritis in that limb. After this loss, he taught himself to write and draw with his left hand. He also walked with a limp, and in his late fifties developed lung cancer. It was this that killed him, at the age of sixty, in December 1843. He was not buried with his parents in Pinner, but instead was buried at Kensal Green, one of London’s new suburban cemeteries. Jane was buried with him after her death in 1858. Unlike the eccentric monument in Pinner, the grave of the Loudons at Kensal Green is simple and conventional, topped by a stone urn commonly found on Victorian graves.

The strange monument Loudon designed to commemorate his parents continues to attract curious visitors to Pinner. One can only guess at the true motivations behind its unique design, and the ‘gruesome’ tale of the supposedly-occupied floating stone coffin, refuted many times but never conclusively proved to be true or untrue, makes this one of Greater London’s most enigmatic grave sites.

References and further reading

Around the Outside, Pinner Parish Church

Monument to William and Agnes Loudon, in churchyard to church of St John the Baptist on south side, Harrow, List Entry, Historic England

“The Story behind Pinner’s Floating Coffin“, Harrow Online, 18th May 2016

Tanya Brittain – “The floating coffin of Pinner – showboating or legal one-upmanship?” Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, 13th March 2019

Woodhall Farm, London Gardens Online

Mr John Claudius Loudon, Parks and Gardens

John Claudius Loudon – On the Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries, Longman, London, 1843

James Stevens Curl – “John Claudius Loudon and the Garden Cemetery Movement”, Garden History 11 (2), Autumn 1983, pp133-156

John Claudius Loudon… and cemeteries, The Gardens Trust blog, 19th June 2014

Ed Jefferson, “Park Life: on John Claudius Loudon, the father of the modern park“, CityMetric, 22nd March 2019

All other newspaper articles referenced in this post were accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.

How interesting. A second reason to visit Pinner, the first of course being the Heath Robinson Museum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the Heath Robinson Museum is wonderful!

LikeLike

This is awesome, and so interesting! I’ve only been to Pinner once, to visit the Heath Robinson Museum, but had no idea this grave was there. Too bad it takes at least an hour and a half to get there from SW London – I can get to Brighton in the same amount of time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s not the most straightforward of places to get to, is it? I visited after staying at a friend’s in Watford so it was a simple hop down the Metropolitan Line, but it took ages to get back to south London! Worth it, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting. Will have to visit Pinner on my next trip to the UK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a lovely place, I hope you get the chance to visit!

LikeLike

Fascinating. I love visiting old graveyards – always full of history and surprising stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! It’s always good to hear from people who share my love for old graveyards!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating post, Caroline. Most intriguing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

What a wonderful post! I came upon it accidentally and am so glad I did. Also enjoying your other articles.

LikeLike

This has been a very interesting read.Thank you

LikeLike

Just a short note concerning the two-headed chicken and the so-called cryptic phrase “I byde my time” in the memorial’s ironwork…they are both heraldic devices of longstanding of the Earls of Loudoun, whose seat is not far from J. C. Loudon’s Lanarkshire birthplace. At the time this memorial was erected, I believe the earldom had passed to the Hastings family, in whose hands it remains today. I don’t know what relationship J. C. Loudon and his family may have had with the title other than the name.

LikeLike

I stumbled across this one during a trip to Pinner that encompassed Heath Robinson and Elm Park Court – never seen anything like the Loudon memorial before!

LikeLiked by 1 person