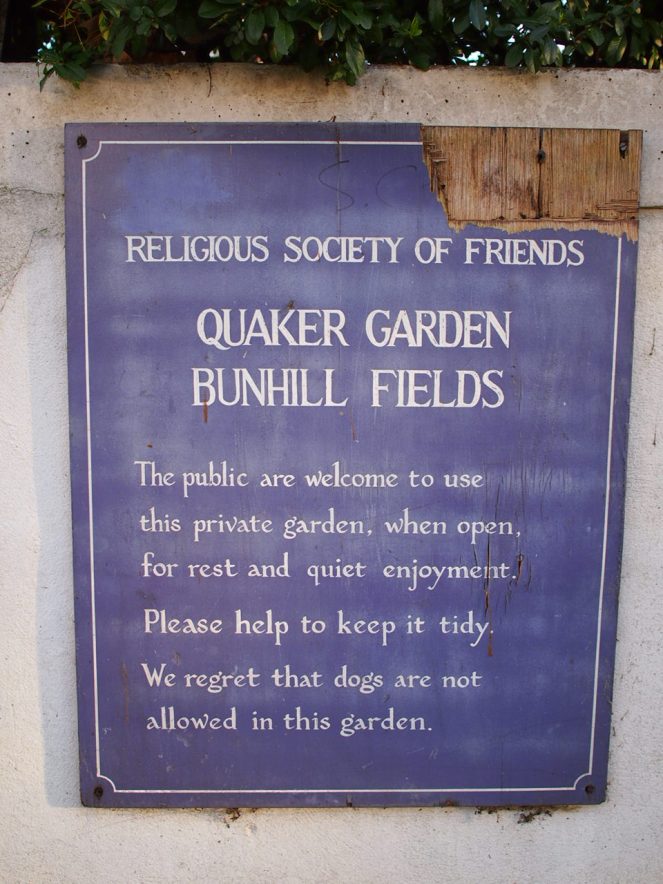

Bunhill Fields, just to the north of the City of London, is one of the capital’s most famous burial grounds and particularly noted as the final resting place of many of London’s nonconformist Christians. Close to Bunhill Fields is another green space, its history as a burial ground much less conspicuous than that of its famous neighbour. But like Bunhill Fields, Quaker Gardens has a long history of burial and religious dissent. I visited Quaker Gardens on a sunny winter afternoon in early 2020 to see what remained of this historic site.

Quaker Gardens, as its name suggests, served as a major place of burial for London-based members of the Quaker movement from the 1660s to the 1850s. The story of this burial ground, and the reasons why it exists separate to Bunhill Fields, helps to tell the story of the Quakers in London: their beliefs, their practices, and their evolving role in this particular corner of the city.

The Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers, first emerged in the 1650s. It was one of many ‘nonconformist’ or ‘dissenter’ Protestant sects that broke away from, or sought to reform, the mainstream Church of England during the 17th Century. George Fox, the founder of the Quaker movement, believed that the relationship between an individual and God was an intensely personal one – and that the need for a church or priests to express one’s relationship with God was not necessary. These ideas brought Fox into conflict with the Church of England, and he was sent to prison on numerous occasions. The term ‘Quaker’ was first used for Fox and his followers as a derogatory term linked to Fox’s quoting of a biblical passage about ‘trembl[ing] at the Word of the Lord.’ Although it began as a derisive nickname, the term ‘Quaker’ soon became more neutral and was used by Friends and others alike.

Quakers became known for their plain dress and teetotalism, their opposition to war and slavery, and their refusal to swear oaths. Rather than attending structured services in a church or chapel led by a minister, Quakers met at a Meeting House and a Quaker meeting might simply consist of Friends sitting and praying in silence. Although the various nonconformist congregations had a common cause in their dissent from the established Protestant Church of England, the Quakers were often singled out for persecution due to their radical beliefs. Their refusal to take oaths brought them into conflict with a law passed in 1662 which required all subjects to pledge their allegiance to the King, while those spreading Quaker teachings were jailed for causing public disturbances and blasphemy. At a time when expressing one’s faith in a different way to the established Church of England was forbidden, the Quakers were seen as dangerous and subversive.

The Quaker burial ground is a little older than the main nonconformist ground at Bunhill Fields – burials of Quakers began here in 1661, and Holmes notes that the Friends had ‘their own special dead-carts’ during the devastating plague outbreak of 1665. It’s thought that around 1,000 Quakers perished during the plague and were buried in this space. Bunhill Fields – originally known as Tindal’s Burying Ground after John Tindal, who took over the land’s lease from the City of London – came into use in 1665. In the mid-17th Century, this area north of Moorgate and the city walls was largely open space, with some areas used for archery practice, and others for windmills.

By the middle of the 18th Century, the area around the Quaker burial ground and Bunhill Fields was becoming more built up. John Rocque’s famous London map of 1746, an extract of which is pictured below, shows buildings and gardens in the vicinity of the burial grounds, with new roads laid out. This development meant that the Quaker ground was now wholly separate from the main body of Bunhill Fields.

Unlike Bunhill Fields, which is crowded with tombs and memorials, the Quaker burial ground was never filled with headstones. Isabella Holmes, writing in The London Burial Grounds in the 1890s, was complimentary of the Quakers’ approach to burial and to the maintenance of their burial grounds – as well as their ‘neat and clean’ cemeteries, she was impressed by their ‘praiseworthy self-control by not wearing mourning [clothes], by avoiding useless expense at funerals, and ostentatious tombstones, memorials, and epitaphs.’ This approach to burial and mourning was in keeping with the Quaker commitment to simplicity and their belief in equality.

A single exception was made: for George Fox, but this was not without controversy. Fox had been buried in 1691 in the same manner as his fellow Quakers, with no marked grave, but a small plaque with the initials ‘G F’ was later attached to the wall of the burial ground. This attracted visitors from all over the country, which angered a ‘zealous’ member of the Friends, Robert Howard. Holmes reported that Howard considered this memorial to Fox, and the visitors it drew to the burial ground, to be idolatrous, and ordered it to be destroyed. The little headstone that commemorates Fox today is a more modern addition to the burial ground.

Although the burial ground close to Bunhill Fields was the largest place of rest for London’s Quakers, other graveyards were established for Friends, many of which disappeared long before the mass closures of London’s urban burial grounds in the mid-19th Century. One such ground was in Covent Garden. John Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows a ‘Meeting House Court’ north of Long Acre, with an entrance on Drury Lane. The burial ground is not indicated on the map, but may well have been adjacent to the meeting house. In 1757, the lease on the land ran out and burials ceased. This burial ground was then built over, and the bones buried there were rediscovered during building work in the 1890s. The remains of the Quakers buried there were then exhumed and reburied at the Quaker burial ground in Isleworth, Middlesex.

As the 19th Century wore on, the number of Quakers living in the area close to Bunhill Fields dwindled. Burial records show that many of those laid to rest in the Quaker burial ground were living in other parts of London – the very last burial to take place was that of Herbert Clarke of Ebury Street, Westminster, who was buried on 3rd September 1854. The burial ground officially closed to new burials on 1st January 1855. Although not in an overcrowded or squalid state, like many urban burial grounds, the central London location of the Quaker burial ground meant that its continued use was deemed to be a risk to the health of local residents – one of the key arguments in support of closing inner-city burual grounds was that the presence of so many decomposing bodies was hazardous to those living nearby.

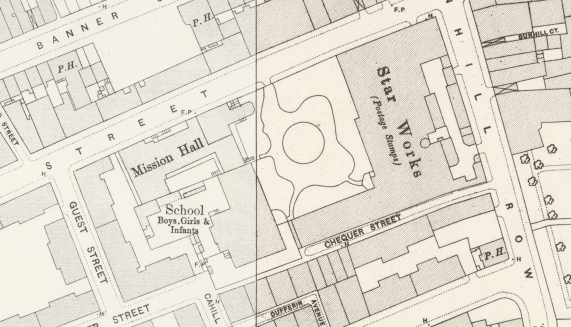

During the 19th Century, development in the area continued to encroach on the burial ground. Part of it was lost to a road-widening scheme, and in the 1870s parts of the burial ground were sold off for the development of a school and dwellings. This was the western section of the burial ground, pictured on the excerpt from Roque’s 1746 map above, but replaced by a Mission Hall and a school in the Ordnance Survey map from the 1890s pictured below. The burials disturbed by the road-widening and the building of the Mission Hall were reburied in a different part of the burial ground.

By the later part of the 19th Century the streets between Whitecross Street and Bunhill Row were overcrowded and poverty-stricken. The disused burial ground sat derelict for about twenty years, before being used as a site for a ‘gospel tent’, where services were held for local people. The gospel tent proved popular enough that an iron structure, large enough to set 400 people, was erected in 1875. When the Metropolitan Board of Works purchased a part of the burial ground for a road-widening scheme, they paid compensation to the Society of Friends and it was this money that helped to pay for a permanent Mission Hall at the site. In the late 19th Century, various religious groups founded ‘missions’ in poor districts of London to provide education, recreation and welfare facilities for the poor, as well as often providing alcohol-free alternatives to pubs and music halls. The Bunhill Memorial Mission Hall, designed by two Quaker architects, was opened in 1881 and included classrooms and lodging rooms, a coffee house, medical facilities and committee rooms as well as a Quaker Meeting House.

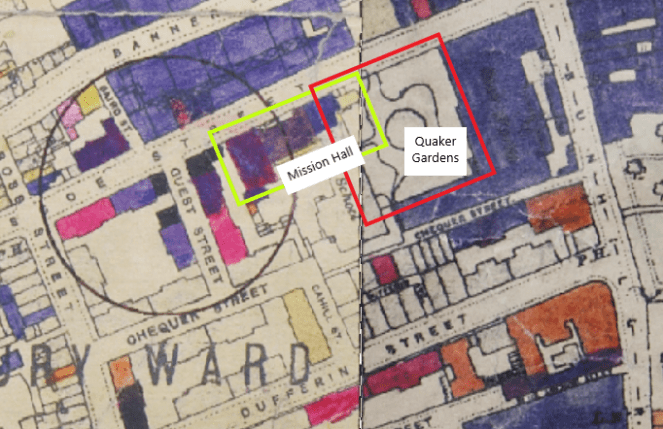

Only a fragment of the sprawing Mission Hall remains today, due to a rocket attack during the Second World War which destroyed most of the Hall. The map commissioned by the London County Council (LCC) to record in detail the extent of damage to the capital’s buildings by enemy action during World War II shows us the devastation in this part of town; the excerpt pictured below, showing Quaker Gardens and some of the streets betwen Bunhill Row and Whitecross Street, shows large areas coloured in purple, indicating buildings damaged beyond repair. The large circle, slightly to the west of Quaker Gardens, indicates the impact site of a V1 flying bomb. These fearful weapons, nicknamed ‘doodlebugs’, had the firepower to take out an entire street, and unlike bombs dropped from aeroplanes, Londoners had far less warning of the approach of a doodlebug. The section of the Mission Hall shaded in yellow (indicating minor blast damage) is the little building we see today.

The remaining fragment of the Mission Hall, originally the site caretaker’s house, was converted to a Quaker Meeting House after the Second World War and its still fulfils this purpose today; a more modest Quaker presence at one of the oldest Quaker sites in the capital. Its large windows and neat brickwork designs give us some idea of how the larger Mission Hall may have looked.

The remainder of the burial ground left untouched by development was laid out as a garden after the Mission Hall was completed, and became a public park after the Second World War, managed by Islington Borough Council. The larger portion of the park is given over to a children’s playground, with other sections landscaped and planted. One area is railed off and designated a dog-free area; it is this section where George Fox’s memorial and the surviving, bomb-damaged stone tablet detailing the histroy of the site can be found.

I visited Quaker Gardens on a sunny Saturday afternoon whilst covering a route for an upcoming tourguiding class. Children were playing football in the playground, their parents gathered in a group to chat and pass the time. Birds chirped and flew from tree to tree. Although only a short distance from the high glass towers of the City of London, this part of London remains largely residential and still predominantly working-class in flavour, despite a great deal of gentrification in recent years. Most of the homes here are postwar social housing developments, with a few older schemes – such as the distinctive yellow Peabody buildings pictured in the background of the photograph below – surviving the Blitz and the march of redevelopment in the decades since. Quaker Gardens is less of a haven for City workers during their lunchbreak and more of a garden for local people to relax, play, walk their dogs and socialise.

The scene is dominated by Braithwaite House, a 19-storey tower block named after Joseph Bevan Braithwaite, Jr, one of the founders of the Mission Hall in the 1870s. He was the son of two Quaker ministers, Joseph Bevan Braithwaite Sr (a well-known conservative within the Quaker movement) and his wife Martha Gillett. Braithwaite Jr was a stockbroker, and played an important role in the early development of electricity supply and infrastructure in Britain at the end of the 19th Century.

Braithwaite House has some interesting tales of its own. Most notoriously, it has a link to the Kray Twins, the infamous East End gangsters. When the family home in Bethnal Green was earmarked for demolition, Violet, mother of Ronnie and Reggie Kray, moved to Flat 43 in Braithwaite House and it was while meeting with associates in this flat that the Kray twins were apprehended by police in May 1968.

I enjoyed the peace and simplicity of Quaker Gardens, particularly the little railed-off section where George Fox’s memorial resides. It feels a world away from the City of London, and is entirely different to its famous neighbour on the other side of Bunhill Row. It is not a place for admiring ornate old gravestones, but its modern-day purpose as a place of relaxation and peace seems very fitting for a site that’s been associated with the Quaker movement for over 350 years.

References and further reading

Quaker Gardens, London Gardens Online

Quakers in the City, 2nd edition (PDF)

Friends Meeting House, Bunhill Fields (PDF)

Notes for visitors to Bunhill (PDF)

Mrs Basil Holmes – The London Burial Grounds: notes on their history from the earliest times to the present day, Macmillan and Co, 1896

Fascinating history. London is full of hidden gems.

I come across Quaker Burial Grounds and Friends Meeting Houses frequently whilst walking in the NW. I search them out as they are always a place of peace and tranquility.

The last one I visited this year was Swarthmoor Hall, Ulverston, which has an interesting history and George Fox lived there for periods of his life.

LikeLike

I love all the hidden burial grounds around London! I can’t remember if I’ve been to this one or not, but your photos are certainly better than mine would have been anyway!

LikeLike

Hi, I wondered where you got the information about Herbert Clarke being the last burial to take place there and if there is any further information you have on his interment?

LikeLike

Hi, I got the info about Herbert Clarke from this webpage (it’s long, so best to ctrl-F ‘Clarke’ to find the short entry on him) – I’m not sure where the original burial records are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

Quaker records are archived at Friends’ House on the Euston Road (opposite the station). The Library is open most weekdays in non-Covid times and it is easy to join and consult the archive. All you need to do is find whatever you want on the indexes and once an hour somebody descends into the vaults and returns with requested materials. You can wait in the reading room or pop off to the cafe or the restaurant for something wholesome served bysomeone on a London Living wage.

LikeLike

Thanks,Really wonderful…….

Quaker burial ground.

LikeLike

The article mentions the reburial of Quaker bones from Bunhill Fields to a Quaker Burial Ground at Brentford and Isleworth Meeting House, Isleworth. This Meeting House and graveyard is still open. There are also many famous Quaker botanists interred or have their ashes scattered there, as it is close to Kew. If you are interested in visiting look online for details for how to get there and when it is open to the public.

LikeLike

Wonderful piece about the burial grounds and Quaker history. Thank you for this post as I learned a lot today about the Quaker movement.

LikeLike

Fascinating – wonderful article – you covered it much more thoroughly than I did on https://bitaboutbritain.com/the-bodies-at-bunhill-fields/ where I kind of merged everything. Loved the inclusion of maps and the detail about the Krays. Assume you’ve been to Fox’s Pulpit?

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this. Really enjoy ALL your work. Thanks from the U.S. of A.

LikeLike

How lovely. Thank you for all this interesting information about the Quaker Friends. I believe my 6x paternal grandmother, Anna Marie ‘Ann’ BOURNE Lamborn (1728-1790) of Chester County, Pennsylvania, is buried here.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed learning the history of Chequer Alley Friends Burial Ground. I have two ancestors buried here, Wm Scarbrough in 1681 and his son John in 1706. I first saw what is now Quaker Gardens in the 1970’s when it was still park-like. So sad it is now completely covered in concrete. I wish I could say my Quaker ancestors here “rested in peace” but it appears that was not to be!

LikeLike