Lower Thames Street isn’t exactly a promising-looking place when it comes to searching for relics of Roman-era London. The wide, busy road cuts through the City, and the buildings that line it are mostly modern, concrete and uninspiring. Yet underneath one of these buildings something wonderful has been preserved: the ruins of a Roman bath house.

There’s very little of Londinium – Roman-era London – to be seen in the modern city. Centuries of expansion, destruction, building and rebuilding have all but destroyed or buried the majority of Roman structures. A few fragments of the old city wall, which was maintained for many centuries after the Romans left, can still be seen close to the Barbican complex and the Tower of London. However, most of the time when Roman remains are found by archaeologists working on building sites, they are covered over again by new buildings and lost to public view.

One Roman site, the Mithraeum, has actually been moved from its original location. The temple to Mithras was discovered in 1954 close to the River Walbrook, but because building work was to go ahead on the site the Mithraeum was relocated to a site nearby, where the remains were reassembled so that they could remain on view to the public. At present, however, it is being relocated to its original site and has been incorporated into the design of the new offices being built there. A number of artefacts from the temple, including a stone head of the god Mithras, are on display in the Museum of London.

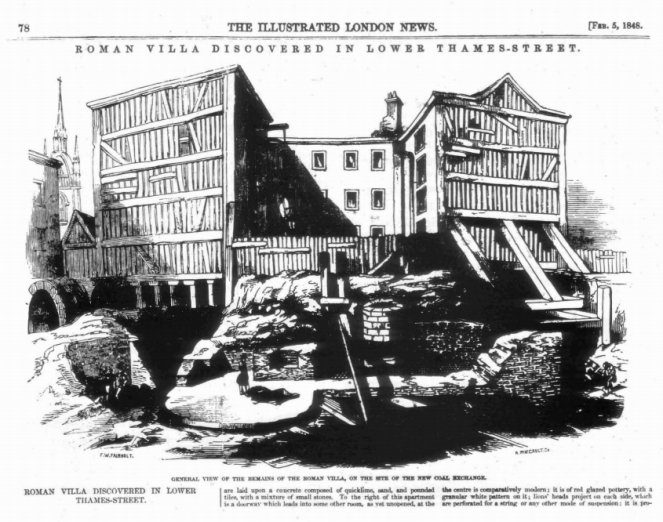

When rebuilding London’s churches after the Great Fire of 1666, Christopher Wren noted finding Roman remains on the sites of many of the churches he designed. There was no such thing as archaeology as we would now understand it at this time – any interesting artefacts found may have been plundered, sold or simply built over. This could have been the fate of the Billingsgate bath house when it was discovered in 1848, but what happened after its discovery served to preserve it in situ.

In 1848 building work began on a new Coal Exchange for London. Demolition work on the site uncovered the remains of a Roman building. The discovery attracted a great deal of interest from the media and when the Coal Exchange was built, the ruins were preserved in the new building’s basement.

It was around this time that the idea of affording ancient monuments special protection was being discussed. In 1871, John Lubbock had purchased the ancient stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire in order to preserve it and protect it from any future developments, and it was with Lubbock’s help that (after a number of failed attempts) the Ancient Monuments Protection Act was passed in 1882. This legislation, supported by the likes of William Morris, is seen as one of the first steps towards state involvement in the protection of Britain’s heritage. The Act protected scheduled monuments against unauthorised changes or demolition. The ruined house at Billingsgate was one of the first sites to become a Scheduled Monument in London and because of this subsequent developments on the site have not destroyed the ruins but have instead ensured that they have been preserved in situ. Building work in the late 1960s, when Lower Thames Street was being widened, uncovered more ruins, including those of the bath house.

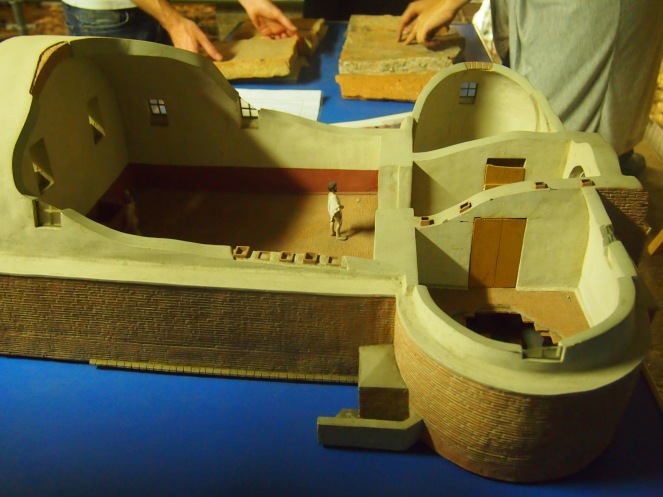

The baths found at Billingsgate are not the like well-known public baths often found in Roman settlements. Londinium had had a public bath house, situated at Huggin Hill, but it was demolished in around 200, possibly due to the expense of maintaining the complex. There is evidence that the population of Londinium declined after its heyday in the 2nd Century, and this may have been one of the reasons behind the closure and demolition of the public baths. The ruins at Billingsgate, on the other hand, date from later in the Roman period – about the 3rd century – and were built in the courtyard of an existing building. This building is thought to have originally been a large private house, but its location close to the edge of the city – and on what was then the riverside – suggests that in later years it may have been an inn or mansio. Constructing a private bath house for patrons of the inn would have made sense as it gave weary travellers a place to wash and relax after a long journey.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of a hypocaust – a furnace which would have provided underfloor heating to the building – and have identified the different rooms of the bath house as a cold room (a frigidarium), a warm room (a tepidarium) and a hot room (a caldarium).

Billingsgate is a fascinating site for archaeologists as it provides an insight into those later, declining years of Roman London. It can be assumed that Londinium was abandoned – officially at least – in 410, when the Romans pulled out of the province of Britannia as they sought to protect the heart of the empire from barbarian incursions. However, the departure of the Roman armies does not necessarily mean that Londinium’s civilian population abandoned the city overnight. Some may have stayed there for months or even years afterwards, and archaeologists working at Billingsgate have found evidence that the site was occupied well into the 5th century. However, the departure of the Roman forces and the collapse of Roman infrastructure in Britain would have had a significant impact on goods being bought and sold in Londinium and most of its inhabitants probably moved away to safer and more prosperous places.

One of the most interesting finds from the site is a Saxon brooch, which is assumed to have been dropped or lost by someone passing or exploring the derelict buildings at Billingsgate. Although Londinium ceased to function as a city after the withdrawal of the Romans, it is possible that people passing through would shelter in its abandoned buildings. Nowadays, it is hard to imagine London as a derelict, overgrown and abandoned place. When Anglo-Saxon settlers arrived in the early 7th Century, they built Lundenwic in the area that is now Aldwych and Covent Garden, a mile or so to the west of Londinium. It wasn’t until the time of Alfred the Great in the 9th Century that the old Roman city was resettled, its defences rebuilt and strengthened. By this time, the house and baths at Billingsgate had fallen into ruin and been buried by soil from the slopes above, and it was forgotten until its rediscovery in 1848.

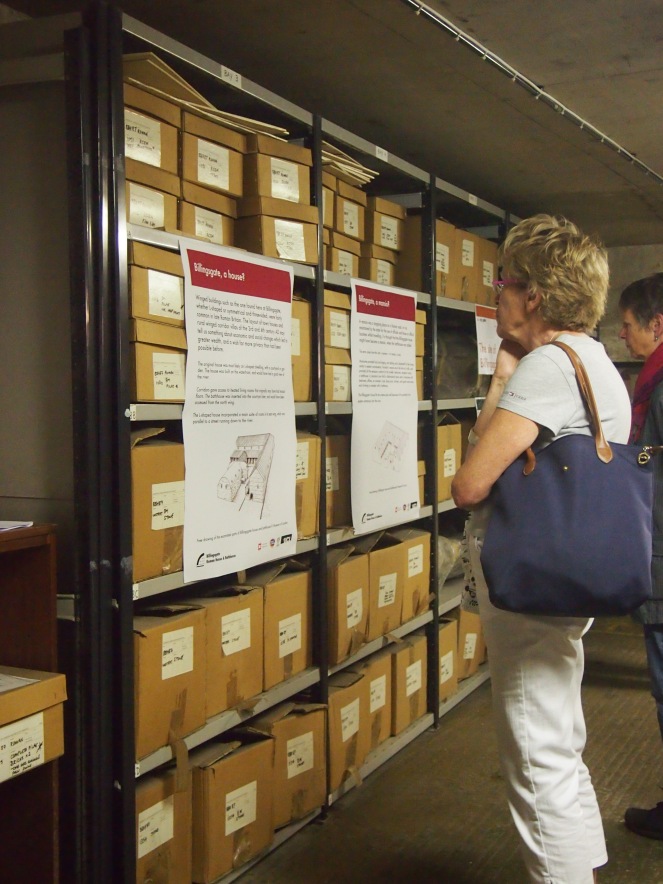

Today, the bath house is only open to the public occasionally, but behind closed doors archaeologists from University College London have been working on the site, looking to discover as much about it as possible and ensure its survival for future generations. Visually, it may not seem as spectacular as a lot of more famous Roman ruins, but it has already yielded a great deal of interesting information on the later years of Roman London and will hopefully continue to help uncover more of the secrets of this period in years to come.

I was able to visit the site as part of the City of London’s Festival of Archaeology in July 2014. The Billingsgate Bath House usually opens as part of Open House Weekend every September, and occasionally opens to the public on other dates too.

References and further reading

Billingsgate Roman Bath House http://billingsgatebathhouse.wordpress.com/

The Billingsgate Roman House and Bath – conservation and assessment, Peter Rowsome (source)

House and bath at Billingsgate, Museum of London http://archive.museumoflondon.org.uk/Londinium/Today/vizrom/07+baths.htm

UCL students help to conserve a piece of London history, UCL News, 13th July 2012 http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/news-articles/1207/UCL-students-help-to-conserve-a-piece-of-Londons-history

Thanks for another fascinating post. Makes you wonder what other ruins remain undiscovered beneath all the modern buildings. It makes sense that the population of London would have stayed there even after the Romans left. After all, it was their home – where else would they go? Where were the ‘safer, more prosperous places’?

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m no expert on the sub-Roman period but from what I’ve read, there were very few settlements that we’d see as towns – I think the majority of people lived off the land, in smaller settlements, and various lords and kings had strongholds. I can imagine that Roman sites were still used and probably occupied to some extent as they were linked by good roads, and ruined buildings could be plundered for building materials. The departure of the Romans seems to have ended the concept of urban living for a few centuries and the reduction in trade and communication with the rest of the empire was probably something to do with that.

LikeLike

Interesting! Thanks for visiting – I feel very daunted by the new camera!

LikeLike

Thank you! New cameras are always a bit daunting, especially when they’re DSLRs – I hope you enjoy getting to grips with yours and I’m sure the results will be fantastic 🙂

LikeLike

Fascinating blog post! I always feel a little humbled to think about what I might be walking around on.

LikeLike

As a teenager, I remember queueing to see the ruins of the Mithraeum when it was first uncovered in 1954. I found it quite exciting to see them so soon after their discovery.

LikeLike

That must have been such a great experience! I am looking forward to the Mithraeum reopening to the public when it has been moved back to its original location (next year, I think) – it is great that it has been preserved, and the building work in that area recently has uncovered some amazing finds.

LikeLike