Situated just to the south of trendy Exmouth Market, Spa Fields in Clerkenwell is today a park that is enjoyed by locals and office workers alike, a rare green space in an area filled with offices, tower blocks and retail units. Only a couple of plaques installed by Islington Council give any indication of the area’s raucous and sometimes dark history.

Compared to what is there today, it’s difficult to imagine Spa Fields (or Ducking-Pond Fields, as it was sometimes known) in the 17th Century – an expanse of open ground, some of it used for farming or duck hunting, at night the haunt of footpads and muggers. In 1685 the pub which gives the area its name was opened. The London Spaw (Spa) was so named as it was on the site of an ancient spring, the waters of which were reckoned to have health-giving properties.

The London Spaw was only one of many attractions that this area held for the people of London at this time. The area was described in the nineteenth century as having been ” the summer’s evening resort of the townspeople, who came hither to witness the rude sports that were in vogue a century ago, such as duck-hunting, prize-fighting, bull-baiting, and others of an equally demoralising character.” (source) The famous Sadler’s Wells theatre was nearby – because the area had a reputation for being rough, torch-bearing “link-boys” were employed by theatre-goers to light their way home across the fields to avoid falling prey to “sneaking footpads.”

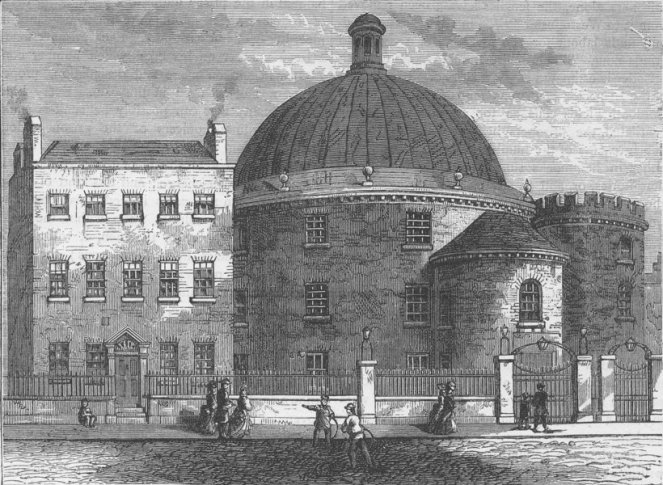

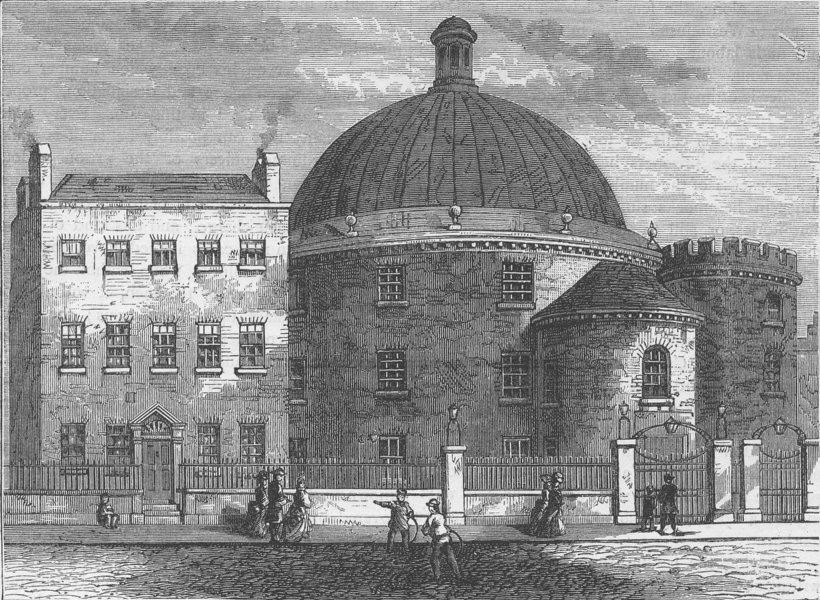

Popular attractions included a number of bowling greens (Bowling Green Lane close to Spa Fields is named after these places), skittle grounds, places where horse and donkey races were held, and tea gardens. Some venues, run by ambitious owners, combined a number of these entertainments. The Pantheon was one such venue. Opened in 1770, it was built to resemble the ancient building in Rome of the same name, and was a space for tea parties, drinking and socialising, with a fancy garden that could be enjoyed when the weather was good. It was a distinctive building inside and out, with its domed roof and galleried interior. The Pantheon’s clientele included “small tradesmen, apprentices, dressmakers, servant-girls, and disreputable women.” This rather dismissive description of the people who enjoyed their leisure time at the Pantheon is typical of attitudes towards the entertainment provided in the Spa Fields area – because it attracted London’s working population, the area was looked down on by more wealthy members of society.

However, the Pantheon did not last long. By 1774, the owner had become bankrupt and the building later reopened as a Dissenting chapel, funded by the pious Selina, Countess of Huntingdon. Walter Thornbury, author of the 1878 book Old and New London, describes the Countess’ charitable work in glowing terms. Selina opened her house up for religious services and funded the building of dozens of chapels, as well as setting up the Spa Fields Charity School for local children. Thornbury claims that in 1780 the Gordon Rioters, who had swept through London destroying a large amount of property, spared the Spa Fields chapel when they were told of its link with the “good countess”.

In 1816, Spa Fields was the site of huge public gatherings which later turned violent and became known as the Spa Field Riots. The first meeting, on 15th November, was a peaceful affair. Attended by around 10,000 people, the Radical politician Henry “Orator” Hunt addressed the crowds and sought to seek popular support for a petition that was to be sent to the Prince Regent. This petition requested electoral reform – full male suffrage, annual general elections and secret ballots – as well as relief from hardship. The years following the Napoleonic Wars were difficult ones in Britain. Thousands of soliders were returning home looking for work and many industries that had been sustained by the years of conflict collapsed, causing widespread unemployment. Henry Hunt was a famous Radical advocate of parliamentary reform and accountability and particularly supported the working classes. He was elected to present the petition to the Prince Regent, but was twice rejected the chance to have an audience with the prince.

A second meeting at Spa Fields was held on 2nd December. On this occasion, Hunt was delayed getting to the meeting and by the time he arrived others, including James Watson and Arthur Thistlewood, were addressing the crowd and inciting violence. Watson and Thistlewood were Spenceans, followers of the ideas of Thomas Spence, a Radical who had campaigned for the common ownership of land and universal suffrage. Accompanied by some sailors, Watson, Thistlewood and their associates began to march towards the Tower of London, looting a gun shop on the way for weapons. As the mob moved through the City of London, a pedestrian was killed and the rioters were eventually apprehended and order restored. When the rioters went on trial, it became apparent that the core group of Spenceans who had incited the violence had been encourged by a man called John Castle, who was in fact a spy and may have been acting as an agent provocateur. Castle’s role led to the treason charges against Watson and the others being dropped. One of the sailors involved in the riots, however, was found guilty of stealing from the gunsmith’s shop on Snow Hill and was executed. The Spa Fields riot was not Arthur Thistlewood’s last involvement in conspiracy – in 1820 he was hanged for his involvement in the Cato Street Conspiracy, which had sought to assassinate the the British cabinet.

The rioting gave rise to legislation that became known as the “Gagging Acts”, which included the Seditious Meetings Act of 1817. This Act, passed to attempt to quell fears of revolution, made it illegal for gatherings of more than 50 people to occur.

The darkest chapter in the history of Spa Fields is undoubtedly the burial ground and the scandalous practices of its owners. Originally the garden of the Pantheon, the space was opened as a burial ground in the 1780s. It was reckoned at the time that there was room for about 2,700 burials there, but the unscrupulous actions of the site’s owners soon started to become clear. As burials were cheaper at Spa Fields than at local churchyards, it was much used by the poorer inhabitants of Clerkenwell and Islington. The burial ground quickly became overcrowded, which made burials vulnerable to the attentions of bodysnatchers. One such “Resurrection Man”, Joseph Naples, was prosecuted in 1802 for stealing cadavers to sell to local medical schools.

Matters came to a head when the police were called to a disturbance at the burial ground in March 1845. Rueben Room, who had recently been dismissed as a gravedigger on the site, was attempting to remove the recently interred corpse of his young daughter. When the police arrived, Room showed the constables the Bone House, where a fire was burning. It became apparent that this fire was being fuelled not only by the wood from coffins, but also with shrouds and human remains.

The horrors of the Spa Field burial ground shocked the public and attracted attention from the media. A long piece in the York Herald in April 1845 describes the dreadful goings-on, including family graves where bodies were “mutilated” and graves reused regularly (with gravestones being moved around to give the impression that parts of the burial ground were unused), as well as distressing reports of women who brought stillborn babies to be buried being aggressively challenged about whether the child had “breathed” before it died – if it had died after birth rather than being stillborn, extra money was charged for its burial. Coverage of the case in the Leicestershire Mercury had the headline “Grave-yard Abominations.”

The absolute disregard for the dignity of the individuals buried there, along with the stench and smoke, made the Spa Fields scandal one of the catalysts for the move towards spacious suburban cemeteries and the closure of London’s inner city burial grounds.

The London Standard reported that, according to a local surgeon, the burial ground was having an appalling effect on the health of those unlucky enough to live close by. “Diarrhoea and fever exist in a more aggravated form in this than in any other part of the parish. These virulent diseases do not exist to more than one-fifth the extent in other parts of the parish that they do hard by the burial ground.” (London Standard, 16th April 1846)

George Alfred Walker, the surgeon quoted by the Standard in April 1846, had previously written about the state of London’s burial grounds, and was the founder of the Society for the Abolition of Burials in Towns. In 1839, he had published Gatherings from Graveyards, a study of burial practices throughout history and a commentary on the unhealthiness of urban burial grounds. Gatherings contains studies of the state of individual burial grounds in London, including Spa Fields – which he describes as being “saturated with [the] dead.” He also raises suspicions about the management of the site, a number of years before the scandal of the practices at Spa Field was revealed to the public. How, he wondered, could such a small space keep accepting more burials? “I can affirm, from frequent personal observation, that enormous numbers of dead have been deposited here.”

After the scandal of the bone house was revealed in 1845, Walker was a very vocal critic not only of the practices at Spa Fields but also of the practice of burying the dead in urban areas. He was dedicated to his cause, and wrote to newspapers all around the country condemning the practices at Spa Fields and making a case for urban burials to be stopped. As his comments recorded in the London Standard demonstrate, he was keen to make the link between unsanitary, choked burial grounds and high rates of disease in the areas immediately around the cemeteries. As a medical man, he was able to speak with some authority on this and his campaigns paid off – a report in the London Daily News in 1847 acknowledges Walker’s work and states that “the next in importance to the reform of the sewerage will be the banishment of all graveyards and burial blaces, by whatever name and designation known, from the purely urban districts of London.” In 1851, the Burials Act prohibited any new burials in built up areas of London.

The burial ground was finally closed in 1853, and in the 1860s the gravestones were removed as part of an attempt to transform the site into a “make belief” garden. This venture failed, as apparently the flowers planted there all died. In 1886, Spa Fields was formally transformed into a public park and became the Spa Fields Play Ground, a space set aside for children that proved hugely popular and was said to have been “a great help to the district”. The distinctive round chapel, once the Pantheon, was demolished in 1886 and replaced with the Church of the Holy Redeemer that still stands there today.

Today, Spa Fields is a pleasant corner of an increasingly gentrified Clerkenwell. Part of the park is still set aside as a children’s playground, and in 2006 the park was landscaped – the distinctive raised areas pictured above were created at this time. I visited the park on an unseasonably mild day, and many people were making the most of the sunshine, relaxing on benches and even on the lawns, enjoying lunches from the trendy food outlets of nearby Exmouth Market. As it was half term, the playground was full of families. Nothing about the space today suggests its previous incarnations, either as a wide open space capable of housing huge crowds at political gatherings, or as a hellish burial ground, choked with the dead. Instead, Spa Fields has returned to its earlier use as a place of recreation, a space set aside to be enjoyed by local people.

References and further reading

The Spa Fields Riots, 2nd December 1816, Marjie Bloy, The Victorian Web, 30th August 2003 http://www.victorianweb.org/history/riots/spafield.html

The Lost Pleasure-gardens of Finsbury and Pentonville, Ventures & Adventures in Topography, 3rd February 2011 http://venturesintopography.wordpress.com/2011/02/03/the-lost-pleasure-gardens-of-finsbury-and-pentonville/

Burial in Spa-fields, The Sydney Morning Herald, 17th July 1845 (source)

Burial-ground incendiarism: the last fire at the bone-house in the Spa Fields Golgotha, George Alfred Walker, 1846 (source)

Unearthing a gruesome secret, Keith Oseman, Who Do You Think You Are? magazine, March 2014 (source)

Gatherings from Graveyards, G. A. Walker, Longman and Company, 1839

Coldbath Fields and Spa Fields, Walter Thornbury, Old and New London Volume 2, 1878, British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45101

Exmouth Market Area, Philip Temple (ed.), Survey of London: volume 47: Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, 2008, British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=119437

A really interesting piece, as always; I knew about the location of the protest and riots, but not about the burial ground. The area Spa Fields covered in its heyday was enormous, all the way up to Angel and close to what is now Pentonville Road.

LikeLike

Thank you! When visiting the area today, it’s hard to imagine how rural Spa Fields would have been 200 years ago.

LikeLike

Spa Fields and Exmouth STREET are mentioned in ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ – I think Kit went by there.

LikeLike