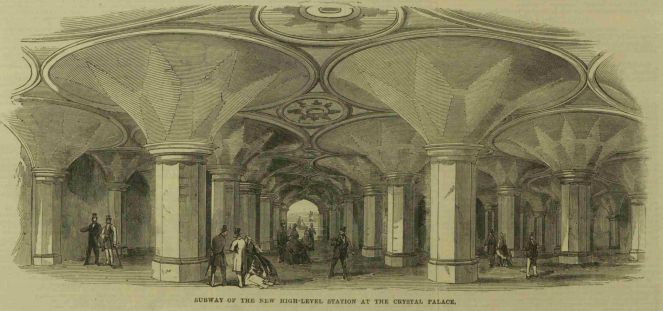

Part of the A212 road runs along one side of Crystal Palace Park, carrying traffic between the suburbs of south east London. However, beneath a section of the road – unbeknownst to those passing above – is a quite astonishing structure, usually hidden from the public. This is a subway, but not of the concrete, graffiti-ed, dubious-smelling variety more commonly seen beneath Britain’s roads: it is something else altogether.

The story of the Crystal Palace subway begins in London’s famous Hyde Park. It was here that the Great Exhibition was held in 1851, with the Crystal Palace as its centrepiece. Within the palace technology, art and manufactured products from all over the British Empire were exhibited, showcasing the work of inventors, scientists and artists. The Crystal Palace, built from cast iron and plate glass, was one of the architectural wonders of the Victorian era, the largest glass building the world had ever seen.

After the Great Exhibition ended, a new home was found for the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, then a distant and largely rural area a few miles south of Charing Cross. An 1864 map of London includes the Crystal Palace area and shows only a few built-up streets, with open fields to the south and a number of larger villas and lodges with a lot of land around them. Once reconstructed in its new home, the Crystal Palace became a venue for concerts and exhibitions, continuing the role it had played to such acclaim in Hyde Park in 1851.

New pubs and shops opened in the area close to the Crystal Palace to cater for visitors, and before long a new suburb grew up to the west of Crystal Palace Park. A new station was built (the present-day Crystal Palace station) to cater for those anticipated to visit the Crystal Palace in its new home, but before long complaints were made about the long walk from this station to the site of the Crystal Palace itself. In response to these complaints, and in the hope of gaining more visitors to the site, work began on a second station, known as the Crystal Palace High Level station.

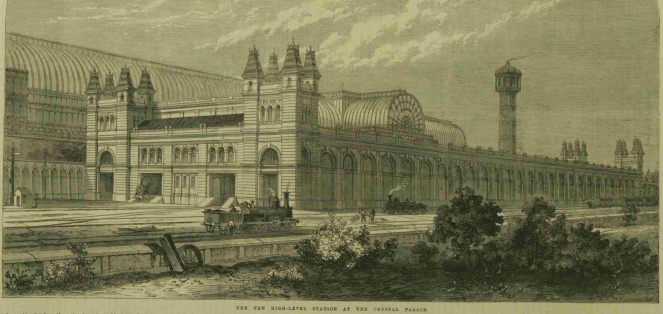

In September 1865, the Illustrated London News ran a story about the opening of the new High Level station at Crystal Palace. As the image below illustrates, this station was built alongside the Crystal Palace, making it much more convenient for visitors. The station and subway were designed by the architect Edward Middleton Barry, son of the famous Charles Barry, whose most well-known work is the Houses of Parliament.

A magnificent vaulted subway was designed to act as an entrance for first class passengers using the station. The subway itself was not quite finished in time for the station’s opening – it opened to the public on 23rd December 1865. The Illustrated London News described it as “handsome and well-lighted.” The subway’s fan-vaulted roof, creating a cool and airy space, makes it feel as though it could be a crypt beneath a medieval cathedral – many Victorian architects took inspiration from the past for their building designs, and the subway certainly provided a striking and fitting entrance to the grandeur of the Crystal Palace.

Despite the opening of the High Level station, visitor numbers to the Crystal Palace never reached the high levels anticipated. For many years it was not open on Sundays, which for many people was the only day that they had off work. The cost of moving the structure to Sydenham – many times more than it had originally cost to build the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park – and the ongoing costs of maintaining such an enormous structure meant that the company that owned it struggled with debt, and the attraction declined over the years, attracting fewer visitors and becoming decidedly more downmarket. The building fell into disrepair, but it was eventually saved for the nation and enjoyed a revival of sorts in the 1920s, featuring regular firework displays and concerts.

After the First World War, the Crystal Palace – after all a space originally designed for exhibiting – was home to the fledgling Imperial War Museum between 1920 and 1924 while its permanent home at the old Bethlem Hospital in Lambeth was prepared. Many huge exhibits, such as the replica gun pictured below, were transported to and displayed at the site.

In the end, the untimely loss of the Crystal Palace, destroyed by fire in 1936, also led to the irreversible decline of the High Level station. The fire drew a crowd of around 100,000 who gathered in the area to watch the structure as it was consumed by the flames, but once the drama was over, the High Level station lost its purpose altogether.

The High Level station can be seen in the top left of the photograph.

(Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

The subway’s underground location led to its use as a public air raid shelter during the Second World War. Plans survive showing how partitions and bunk beds were positioned in the subway. It was large enough to accommodate just under 200 people during the night, with room for more people possible during daytime raids if the beds were not needed. To cater for those sheltering from the bombs, drains also were added to the subway. Even with the partitions added, the subway must have made for a cold, draughty and rather miserable place to wait for the all-clear, and its location so close to the ground’s surface would have meant it would not have survived a direct hit from a bomb or rocket.

The High Level station, already little-used and falling into disrepair, closed for good in 1954. In the years that followed, the station was demolished but the subway remained. It was used as a means of access for vehicles participating in motor racing events at Crystal Palace Park, and its beautiful design attracted many photographers, but it also became neglected and vandalised.

Eventually, the subway was sealed up more effectively to deter any further vandalism, and it was Grade II listed by English Heritage in 1972.

Since the late 1970s efforts have been made to reinvent the subway as a community space. The first ‘Subway Superday’ – a community event organised by local groups the Crystal Palace Foundation and the Norwood Society – took place in September 1979, with the final one taking place in 1994. These Superdays drew large numbers of visitors, and featured stalls, music, dancing and performances. Videos on the Friends of Crystal Palace Subway website document people’s photographs and memories of these events. The subway also hosted an number of raves during the 1990s, and was featured in the video for the Chemical Brothers’ single ‘Setting Sun’ in 1996.

After many years of being inaccessible to the public, the subway opened its gates for the London Open House Weekend in 2014, attracting a large number of visitors. Its open days have proved to be very popular, with visitors enjoying its beautiful, almost timeless appearance. The Friends of Crystal Palace Subway are working hard to raise money to ensure that the site can be re-opened on a permanent basis, to allow Londoners to once again enjoy this wonderful place.

I visited the Crystal Palace Subway as part of the Crystal Palace Festival, on 18th June 2017. Details of future open days can be found on the Friends of Crystal Palace Subway website.

References and further reading

Friends of Crystal Palace Subway

Pedestrian subway under Crystal Palace Parade, List Entry, Historic England

History of IWM, Imperial War Museums

The 80th Anniversary of the Crystal Palace Fire, London Fire Brigade, 30th November 2016

Very well done. I believe a Paxton designed the Crystal Palace. Wonderful spot. Id like to visit and see all these magic spots. Your friend Bruce

LikeLike

From another Bruce. A wonderful and interesting post, Caroline, as usual. I love your exploration of out-of-the-way places.

LikeLike

What an amazing place! I’m glad to know it is being preserved, and opened occasionally to the public. So much art and skill has gone into its creation, it’s a shame to see it decay.

LikeLike

i used to live 5 minutes walk from there but didn’t know anything about the underground marvel. In some ways i think the area around Crystal Palace never got over the fire in the 1930’s.

LikeLike