Although the Northumberland village of Bamburgh is dominated by the fortress that has stood on its cliffs since the 7th Century, one figure who looms large in the area’s history is not a king or a warrior, but an ordinary woman whose act of bravery in 1838 made her internationally famous. Grace Horsley Darling’s role in the rescue of sailors from the wrecked vessel Forfarshire in September 1838 was widely covered by the media both in Britain and further afield, and led to an outpouring of donations, gifts and even offers of marriage. The veneration of Grace Darling was not unlike the cults that grew up around many medieval saints, with souvenirs featuring her likeness being sold, items belonging to her and her family put on display or up for sale, and songs and poems being written about Grace and her deeds. Despite her untimely death from tuberculosis at the age of 26, Grace remained a well-known figure, celebrated for her bravery and her Christian values. The fame of Grace Darling provides a fascinating insight into the way that the 19th Century media helped to create modern-day heroes, and how Grace’s character reflected the period’s idea of the virtuous woman.

Grace Darling’s family had an unusual life, even before the event that catapulted Grace to fame. Grace’s father William Darling was a lighthouse keeper, and although Grace was born on the mainland, in Bamburgh village, in 1815, she spent much of her life in the Farne Islands. These rocky islands – home to colonies of thousands of seabirds – have been hazardous to shipping for centuries, and many ships came to grief there. Having a lighthouse on the islands helped to alert passing ships to the danger of the rocks, but wrecks were still common in the area due to stormy weather blowing ships off course. William Darling and his family were originally stationed at the lighthouse on Brownsman Island, which had been home to a lighthouse since 1800. The lighthouse keeper’s cottage still survives today, along with the ruins of the lighthouse towers.

In 1826, the Darling family moved to a new home on Longstone Island. This new lighthouse was located in a better position, a little further out to sea, and although it looks more modern than its predecessor on Brownsman Island it was an extremely isolated place to live. Longstone Island was very rocky, and the Darling family continued to use their old vegetable garden on Brownsman Island to grow food for themselves. Although the Farne Islands are only a few miles offshore from Bamburgh and North Sunderland, stormy conditions could cut the islands off from the mainland for days or weeks at a time – even today, rangers who work with the seabirds on Inner Farne can be cut off from the mainland for many days during bad weather. Although William was officially the lighthouse keeper, the whole family were involved in keeping the operation running – as well as growing food, the Darling family collected eiderdown from the island’s many eider ducks, and mended clothes. William and his wife Thomasin also educated their children at home, as the lighthouse’s isolated location made it very difficult for the children to attend school on the mainland. Most importantly of all, the women of the family would step in as lighthouse keepers when the men were out at sea, ensuring that the light kept burning.

On 7th September 1838, a terrible storm hit the Farne Islands and a paddle-steamer, the Forfarshire, making its way to Dundee, was blown off course and was wrecked off the Farne Islands. The ship broke in half, and many of the 60 or so souls aboard were quickly lost to the waves. However, as visibility improved, 22-year-old Grace and her parents on Longstone could see a number of survivors clinging to rocks and wreckage. Conditions were still terrible and the sea was too rough for the lifeboat to be launched from the harbour at nearby North Sunderland (Seahouses). Despite the danger of a rescue attempt, Grace and her father climbed into a small boat and rowed to the survivors, and Grace kept the boat steady while her father helped four men and one woman into the boat. The woman, named Mrs Dawson, had spent the night clinging to the bodies of her children, who had not survived the wreck. After safely getting these survivors back to the lighthouse, William Darling and some of the men he had helped to rescue rowed out again and were able to save four more people. The survivors were looked after by Grace and her family at the lighthouse until the weather improved enough for them to return to the mainland.

Grace’s role in this rescue was quickly picked up by the press. News about shipping, including shipwrecks, was a common feature in newspapers at the time. Much of the British Empire’s wealth and power was founded on naval dominance and international trade, and local and national newspapers carried news of the coming and going of ships from all over the world – this included reporting shipwrecks. What made the wreck of the Forfarshire unusual – and therefore eye-catching – was the involvement of a woman as a rescuer.

Although early reports of the rescue mention both Grace and her father (and indeed, both of them were awarded a medal of bravery by the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck) , Grace soon became the sole focus of interest in the case, with many romantic and dramatic accounts of her role in the rescue filling newspaper columns. Poems were written about her, including the one pictured below, which appeared only a fortnight after the wreck of the Forfarshire.

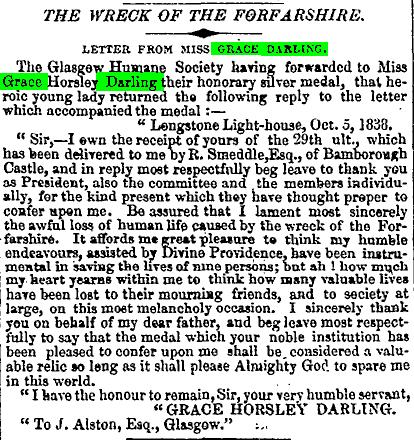

Grace was described by one newspaper as a “young, slender woman” and other reports emphasised her modesty, humble nature and femininity. A letter from Grace herself was printed in the Times, which gives an impression of Grace as a polite, modest individual who preferred to thank and praise God for her role in the rescue rather than emphasise her own strength and bravery. All of this made her an ideal role model for young women of the period, and her story appeared alongside those of Joan of Arc and Lady Jane Grey, amongst others, in a book entitled ‘Lessons from Women.’

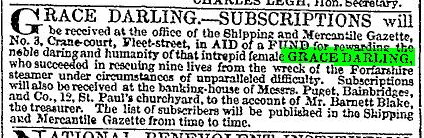

Many of those moved by Grace’s story sent her money, and as the newspaper advertisement pictured below shows, subscription funds were set up for her. The Darling family lived simply at Longstone, and the sudden influx of money must have come as quite a shock. Grace was befriended by the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland, who helper her set up a trust for her to manage the money and other donations that had flooded in as her fame increased.

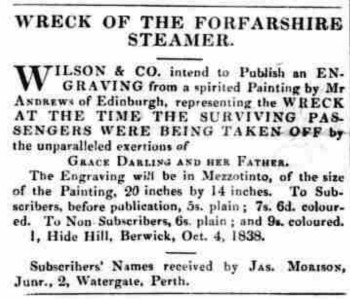

Many people sent money to Grace, and others capitalised on her fame and the affection she was held in to make some money for themselves. Within weeks of the rescue, newspapers all over Britain were advertising Grace Darling memorabilia. Her likeness appeared on all kinds of objects, from artworks to figurines, chocolate wrappers, and tins of tea. Many examples of Grace Darling memorabilia can be seen here.

This sudden fame must have come as a shock to Grace. In a very short space of time she went from being Grace Darling, who lived with her family at Longstone Lighthouse, to Grace Darling, a national heroine, her name appearing in newspapers around the world. Her simple life at the Longstone Lighthouse was suddenly dominated by writing letters to thank people for the gifts they had sent her, or sitting for portraits as artists travelled to the Farne Islands to record her likeness. Grace even received several offers of marriage, all of which she declined. Her reaction to the fame brought about by her role in the Forfarshire rescue was simply to stay at home and continue to help her family keep the lighthouse running. Her older sister Thomasin later wrote in a book about Grace’s life:

She had offers of marriage, but none that she entertained. She clung to her father and to her name, and used to say that any husband of hers should take it. She was in the right; it had become a name for sons to be proud of, known throughout the kingdom, and beyond.

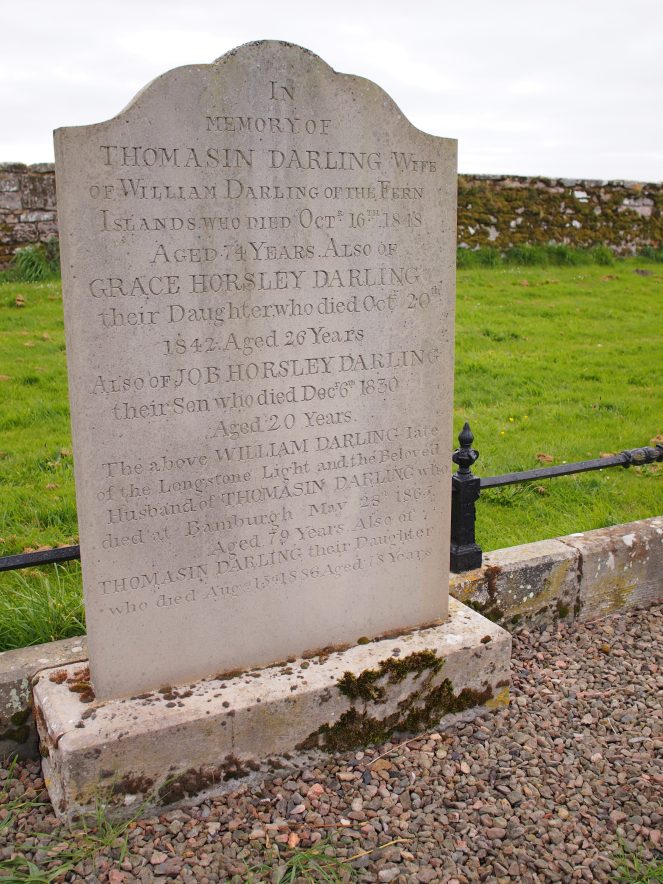

Tubercolosis was a common scourge of the 19th Century, and Grace became ill with this awful respiratory disease only a few years after the Forfarshire rescue. She died in Bamburgh on 20th October 1842, aged just 26. Despite her short life she had become one of the most famous women of the 19th Century. Her early death prompted an outpouring of grief, and her funeral was attended by hundreds of people. Newspapers all over Britain carried reports of this event, with the Bristol Times and Mirror one of those publications which also carried a moving account of her final illness: “She was never heard to utter a complaint during her illness, but exhibited the most Christian resignation throughout. Shortly before her death she expressed a wish to see as many of her relations as the peculiar nature of their employment would admit of, and, with surprising fortitude and self-command, she delivered to each of them some token of remembrance.” (Bristol Times and Mirror, 5th November 1842) Grace was laid to rest in the churchyard at St Aidan’s, Bamburgh, close to many of her ancestors.

A few yards away from the Darling family grave at St Aidan’s is a large memorial to Grace, a beautiful effigy covered by a Gothic canopy – the kind of memorial one might see raised above the tomb of a princess or duchess in a great cathedral. This memorial was created in 1844, funded by donations from the public. The most high-profile of these donors was Queen Victoria herself. The original canopy was destroyed in a storm in 1893; the one we see today is of a different design to the original.

The memorial’s effigy of Grace dates from 1885; an earlier effigy was made of a type of stone that quickly became worn by the elements and was removed inside the church before it sustained further damage.

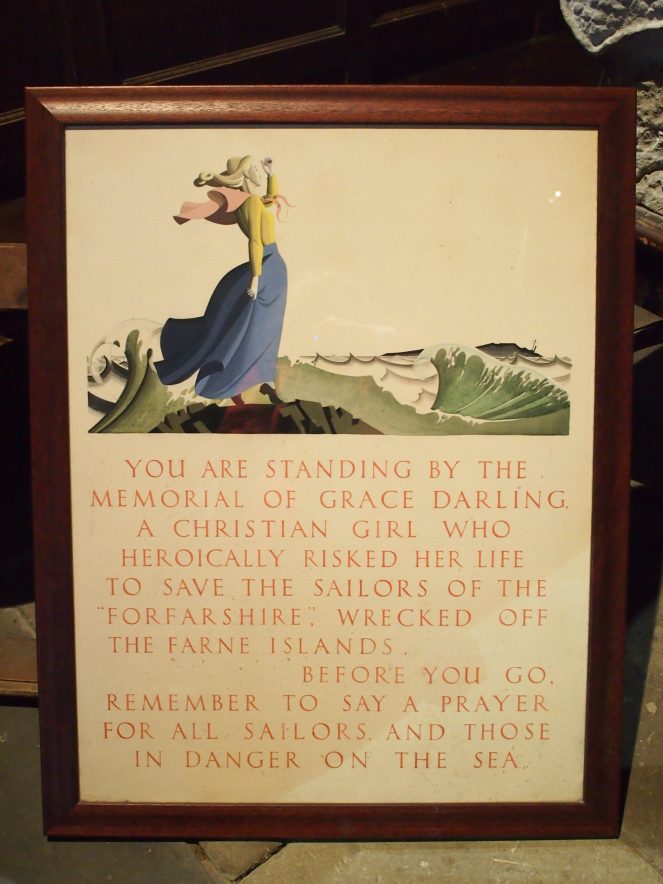

Another memorial to Grace can be found closer to her home in the Farne Islands, on the island of Inner Farne. This island is best known as the place to which St Cuthbert retired as a hermit in the final years of his life in the 7th Century, and today Inner Farne is home to a little medieval chapel as well as a lighthouse and thousands of seabirds. Inside the chapel, a stone table, inscribed with a poem, commemorates Grace.

It is now almost 180 years since Grace and her father rowed out into the storm to rescue the Forfarshire’s stricken passengers, but Grace’s legend continues to inspire. It was the widespread media coverage of her bravery that cemented her fame, and made her one of the best-known women of the 19th Century. A museum about Grace was opened in Bamburgh in 1938, to mark the centenary of Grace’s heroic actions, and is still open to visitors today. Run by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), it exhibits items that belonged to Grace, and many examples of memorabilia produced that show her likeness. The lifeboat based in Seahouses today is named Grace Darling, and her story continues to shine brightly on Northumberland’s stormy coastline.

References and further reading

The Grace Darling Website – Legendary Victorian Heroine http://www.gracedarling.co.uk/

Royal National Lifeboat Institution – Grace Darling Museum https://rnli.org/find-my-nearest/museums/grace-darling-museum

Thomasin Darling – Grace Darling, her true story: from unpublished papers in the possession of her family, 1880 https://archive.org/details/gracedarlingher00darlgoog

A brave woman. There was an obivious need to promote her virtues in Victorian times. Sudden fame seems so modern.

LikeLike

Dear Caroline, I like the story. It was tragic though her dying at the age of 26 years. Ships should have been engineered properly back then with power. Sailing back then was foolhardy for everyone and everything. Those sailers were very fortunate to have been saved by her and her father. From your friend Bruce K. Paxton

LikeLike

Excellent article!

LikeLike

I’ve heard the story of Grace Darling, but it was nice getting to learn about her life before the rescue as well! She sounds like a very interesting woman, and her memorial is beautiful!

LikeLike

Have just found your blog while I was looking for some information on churches. Love this post for two reasons. We have spent a meany happy holiday in Northumberlad. Has to be my favourite place to go.

This last year my interest in churches, castles and history has grown after a trip to Edinburgh, you have visited many a place I know.

You take stunning photos and like all the information….

Amanda xx

LikeLike