If you follow a flight of steps down from Edinburgh’s busy Princes Street you’ll find a church, largely hidden by trees and surrounded by an extensive burial ground. This is St Cuthbert’s Kirk, a site with a history going back many centuries. The kirkyard at St Cuthbert’s is home to some exceptional examples of funerary architecture, imposing memorials and beautifully-carved headstones that give the visitor an insight both into the way Edinburgh’s residents of the past viewed and commemorated death, and the exceptional skill of the people who designed and crafted the memorials.

The kirk is thought to have been founded by St Cuthbert himself, who visited Edinburgh in the 7th Century, and burials may have been taking place on this site for over 1,000 years. The earliest existing record of the burial ground dates from 1595. The present church building dates from 1892; it is the latest in a series of buildings that have existed on the site since at least the 8th Century, and is of an unusual architectural style for a Church of Scotland building. When it was first built its ornate Baroque design was controversial, an architectural style more closely associated with the Roman Catholic church.

It is hard to picture it now, but until relatively recently St Cuthbert’s stood in a very rural spot, some distance away from the built-up area of Edinburgh. This isolation made the burial ground a soft target for bodysnatchers in the 18th and early 19th Centuries, who were paid handsomely by anatomists for fresh corpses to dissect for their research. Legally-acquired bodies for anatomical research were hard to come by – only a few bodies of executed criminals were made available to surgeons, and the demand for cadavers to dissect far outstripped the legal supply. Snatching freshly-buried bodies from cemeteries became a lucrative business in Edinburgh, which was home to a number of medical schools. The most famous individuals connected with this illicit trade in corpses are the murderers William Burke and William Hare, who – rather than risking getting caught robbing graves – simply murdered people and sold their bodies directly to the anatomists. It was the high-profile murders by Burke and Hare that helped to gain support for the Anatomy Act of 1832, which made it easier to legally acquire cadavers for dissection, and as a result of this law being passed the practice of bodysnatching eventually became a thing of the past.

A number of incidents involving ‘resurrection men’ have been recorded at St Cuthbert’s. By 1738, incidences of bodysnatching were severe enough to warrant the building of a high wall around the kirkyard, replacing an older stone wall that had only needed to be sufficiently tall enough to keep sheep out of the burial round. One of the kirk’s own Beadles was implicated in several cases of corpses being stolen at St Cuthbert’s in 1742, leading to the Beadle in question having his house burned down by an angry mob. Despite these incidents, it was not until 1827 that a watch tower was erected on the kirkyard’s boundaries, although in earlier years guards were paid to patrol the burial ground at night.

For the first few centuries of its existence, the rural location of St Cuthbert’s meant that its burial ground was fairly small. Burials took place in a small hill, or ‘knowe’. By 1597 the wall around the kirkyard had fallen into such disrepair that horses and other animals were able to get into the burial ground and graze on the grave sites. It was only in the 18th Century, when Edinburgh’s New Town was developed, that the burial ground at St Cuthbert’s began to expand. The first major extension occurred in 1701, and the draining of the Nor’ Loch, a wet, marshy area to the north of Castle Rock (site of the present-day Princes Street Gardens), allowed the churchyard to be expanded again in the 1780s.

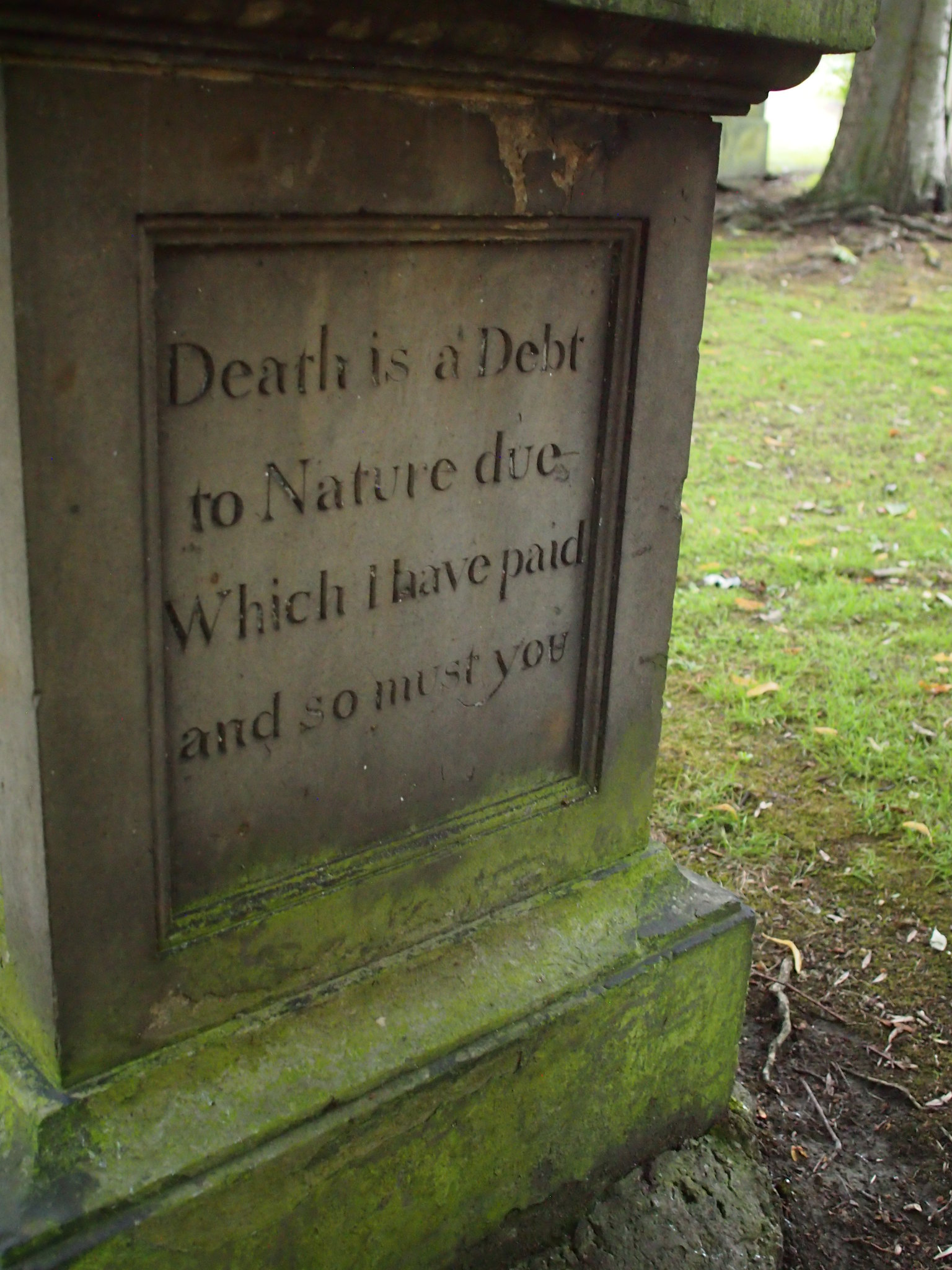

The years of expansion at St Cuthbert’s coincided with a remarkable period where many Scots commissioned elaborate and detailed gravestones to mark the resting place of their family members. As well as showcasing the extraordinary talents of the people who carved these stones, the many well-preserved graves at St Cuthbert’s give the historian an amazing insight into the ways in which death was visualised and commemorated in Edinburgh in this period.

The most recognisable and macabre of the symbols found on the old gravestones at St Cuthbert’s are death’s heads – skulls. The symbolic meaning of the skull on a gravestone is fairly self-explanatory – it represents death, and the reminder that the person viewing the gravestone will also face death one day.

Carved skulls can be found on graves from the 17th and 18th Centuries, and depending on the skill of the carver may be of a simple or more complex design.

Other bones are sometimes featured on gravestones, in particular the crossed femur bones, which can be seen on the monument pictured above. This monument also features crossed scythes – a nod to the scythe-carrying figure of Father Time – and the crossed spade and turf-cutter that represent the tools of the sexton, the person employed to care for a graveyard and dig graves.

Although a feature of some Scottish gravestones from this period is to include images representing the tools of the trade or occupation of the deceased, the presence of so many crossed spades and turf-cutters points to the presence of sexton’s tools on a gravestone as being a memento mori symbol, rather than suggesting an unusually large number of sextons buried at St Cuthbert’s.

The Latin inscription at the top of the gravestone pictured above can be translated as: Death is certain, the hour uncertain. Today it is me, tomorrow it will be you. Marking the grave of John Mason, a student who died at the tender age of 27, another part of the inscription laments his early passing:

O Death, O Grave why so severe

Ev’n youth Must See thy Looks Austere

This young Man did by Living die,

By Death he lives Eternally

The gravestone pictured above also features hourglasses, another common symbol found on 18th Century gravestones in both Scotland and England, representing the passing of time.

The square and compasses carved in the oval in the monument above indicate that this grave commemorates a member of the Freemasons – it is a relatively common symbol found not just on 18th Century graves but on Victorian ones too, and several examples of it can be found in the kirkyard at St Cuthbert’s.

One of the most familiar motifs from 18th Century burial grounds – well-represented at St Cuthbert’s – are cherub-like faces and figures. The winged cherub face, as shown on the gravestone above, represents the immortal soul ascending to heaven.

The two figures on the headstone below are holding quills, and another object which might be a scroll, or a trumpet. They may represent angels of the resurrection. In the Book of Revelation, it is said that the names and deeds of the righteous are recorded in the Book of Life:

The books were opened: and another book was opened, which is the book of life: and the dead were judged out of those things which were written in the books, according to their works.

The figures represented on the grave of Margaret Loch and her family may be making a reference to this particular passage of the Bible (Revelation 20, verse 12).

The rather unusual figures pictured below, with long hair, have been slightly damaged but can still be seen to be holding upturned torches, a symbol more commonly seen on Victorian graves which represents the idea of life extinguished. These figures represent mourning.

The winged figure presenting a crown, carved onto the gravestone below, presents a more hopeful image. The idea of the crown of life gives hope beyond death. Like the grave of Margaret Loch, this image makes reference to the Book of Revelation, this time with an inscription above the image from Revelation 2, verse 10:

Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give the[e] a crown of life

Although many of the symbols and inscriptions depicted on these graves at first glance appear dark and harsh to our 21st-Century sensibilities, I was struck by the messages of faith and hope also contained on the memorials – alongside all the talk of death, and the awareness of it, reminders of the hope of eternal life after death were also present.

Although the later tombstones at St Cuthbert’s are less elaborate in design than their 18th Century predecessors, they are rich in information about the social and professional lives of the people whose burial places they commemorate – Flickering Lamps will be returning to St Cuthbert’s in another article soon to take a closer look at the stories these 19th Century tombs tell.

The kirkyard at St Cuthbert’s may not be Edinburgh’s most famous burial ground (that distinction belongs to Greyfriars Kirkyard, which we’ll be exploring in another upcoming article), but for those interested in the beautiful designs used on old Scottish gravestones, it’s the perfect place to spend a couple of hours wandering among the stones.

References and further reading

Betty Willsher – Understanding Scottish Graveyards, Chambers (Edinburgh), 1985

“Unearthing the City’s Original Bodysnatchers,”The Scotsman, 21st June 2002

Scottish Record Society: Monumental Inscriptions in St Cuthbert’s Churchyard, Edinburgh, J Skinner & Company (Edinburgh), 1915 (PDF)

Excellent article. I was there this week myself!

LikeLike

Your story is very perceptive of the struggle the peoples endured at the time and their rationalization of death and the afterlife as well as what this could possibly mean to others seeing a graves artistic and moral values. This could be a fantasy recreation in the hope of achieving some devine connection with God and finally peace in salvation in being with the creator. This story reminds me of the suffering peoples went through (at the time) with getting heating and lighting in the home to stay alive. Bruce

LikeLike

Very well done. Keep up the good work. Bruce

LikeLike

Wonderful stones, as a carver myself I’m quite inspired by the Scottish tradition of bold relief and simple stylised design

LikeLike

I’ll be in Edinburgh I a few weeks time and will definitely have a wander through this interesting Graveyard. Great article complete with all the wonderful pictures

LikeLike

Very interesting article and photographs. I was in Rome recently and spent a couple if hours at the non-catholic cemetery where Keats is buried. The sculpture on the gravestones was truly awesome. Amazing and some very modern.

LikeLike

Lovely photography and information, as always – the patina on the headstones is absolutely wonderful – and the “teasers” for future posts gives me something to look forward to – keep up the great work!

LikeLike

Excellent article – I actually prefer St Cuthbert’s to Greyfriars Kirk (although that may be because it doesn’t find itself inundated with tourists in the same way as Greyfriars).

LikeLike

Very neat but offers little or no future in any turn of events suposedly purported by the crown (at the time). The picture offered only suggests the aftermath of many many years of suffering from cold, overwork and starvation typified by the British endeavor (to date). Good work Bruce K. Paxton

LikeLike

very interesting and helpful, thank you

LikeLike