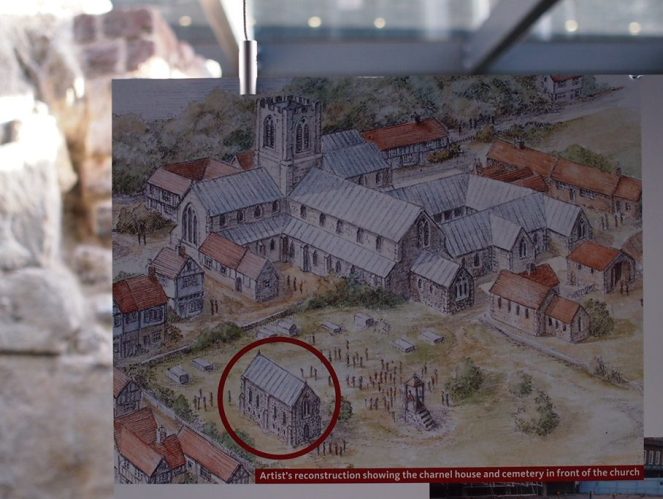

Today, Spitalfields often feels like something of a battleground between the area’s rich and varied heritage and the seemingly unstoppable march of gentrification and redevelopment. Located on the north-eastern edge of the City of London, in recent decades it has been transformed from a mostly working-class district that was home to textile producers and a large fruit and vegetable market to a hub for high-end boutiques and trendy restaurants. It was the construction of a new office block in 1999 that led to the rediscovery of a medieval charnel house – the oldest building in Spitalfields – which had lain undiscovered for around 300 years. Fortunately, the discovery generated enough interest that the office developers chose to incorporate the building’s remains into the new development, and today a glass panel allows the charnel house to be viewed from street level, while a flight of stairs leads down to the ruins themselves, which can be seen behind glass. This little building gives the visitor a rare glimpse into medieval Spitalfields which was home not to market buildings or office blocks but to a hospital and an extensive burial ground.

Since the 1980s, large-scale redevelopment in Spitalfields has enabled archaeologists to make many discoveries, helping to paint a more detailed picture of this area’s past. The archaeological digs and subsequent research were well-funded by the developers of the land, which allowed for money to be spent on analysis of the remains, buildings and artefacts found there, including carbon dating and even facial reconstruction.

The development of Spitalfields has always been linked to its proximity to the City of London. For much of its history, its location just outside of the city walls meant that it was used as a place of burial for London’s dead, beginning in the Roman period (from 1st Century to the early 5th Century). Roman burial custom dictated that the dead were considered unclean and that their remains should be interred away from places where people lived and worked. Spitalfields is located close to two of the Roman-era city gates, Aldgate and Bishopsgate, where roads led out of the city to other settlements.

The discovery of a Roman stone sarcophagus, the lead coffin inside containing the remains of a wealthy woman, remains one of the most famous Roman-era burials excavated in London, but this woman was just one of hundreds of Roman-era burials uncovered in Spitalfields in the 1980s and 1990s. These burials were a mixture of inhumations (burial of an intact body) and cremated remains, some buried in coffins or alongside grave goods. Scientific analysis revealed that one girl buried in Spitalfields was the daughter of a woman from north Africa, while the famous ‘Spitalfields Lady’ whose face was reconstructed (and whose coffin is now on display at the Museum of London) was found to originally be from Rome itself.

London’s centre of gravity moved west in the centuries after the end of Roman rule in the early 5th Century, with the Saxon settlement of Lundenwic centred around what is now Covent Garden. There is little archaeological or written evidence to indicate what happened in Spitalfields at this time. In 886, Alfred the Great re-established the city (now referred to as Lundenburgh) within the safety of the old walls of Londinium as a response to attacks from Danish invaders. In the more peaceful years following the Norman Conquest of 1066, various religious foundations were set up on the edges of London and Spitalfields became home to the priory and hospital of St Mary, which was founded in 1197.

The hospital was one of many founded in and around London in the years between the Norman Conquest and the Reformation of the 1530s. A medieval hospital was very different from modern hospitals as their main priority was to provide spiritual, rather than medical, care. The word ‘hospital’, in fact, comes from the Latin hospes, which means ‘host’, ‘guest’, or ‘stranger’ – the word ‘hospitality’ has the same root. Traditionally, monastic foundations provided hospitality to travellers and pilgrims, and separate buildings were often set up to house these guests. They became associated with the treatment of the sick as people who had become sick on their travels would stay at a hospital until they recovered.

Like many other similar instituions, St Mary’s Spital was home to a community of Augustinian canons and lay brothers and sisters. As well as being “founded to receive and entertain pilgrims and the infirm who resorted thither until they were healed” (source), St Mary’s was known to have provided beds for pregnant women until they gave birth, and to care for any children whose mothers died at the hospital. Those who died at the hospital were buried in a graveyard close to the hospital buildings. The district’s name of Spitalfields comes from its association with St Mary’s hospital and the open spaces around it.

This burial ground at Spitalfields served a dual purpose in the medieval period – as well as serving as the graveyard for the hospital at St Mary’s priory, its location so close to the City of London also meant that it was also used as an emergency site for mass graves in times of unusually high mortality. Archaeologists discovered that a number of mass graves were dug, as far as possible from the hospital buildings, on numerous occasions throughout the medieval period (the earliest burials actually took place several decades before the priory and hospital were founded). Some of these mass graves would have been dug at times of widespread sickness, such as – most famously – during the Black Death plague outbreak in the late 1340s, but famine was also a regular occurrence in medieval Europe. As well as causing many to die from starvation, famine also had the knock-on effect of weakening the surviving population, making them more susceptible to infectious diseases.

In 2012, results of research carried out on skeletons found at Spitalfields identified a catastrophic famine that happened in the middle of the 13th Century – large numbers of people buried in mass graves were found to have died in about 1257-8, and scientists believe that a huge volcanic eruption in the tropics at this time caused global temperatures to fall sharply, causing crops to fail. A contemporary chronicler estimated that around 15,000 Londoners (out of a population of about 50,000) died as a result of this famine, with many of them interred in the emergency pits at Spitalfields. One theory is that some of those buried at Spitalfields might have been travelling from rural areas into London in search of food and work, but on arrival were too weak or sick and died in the priory hospital.

As a large burial ground that was much-used over the space of several centuries, it would not be unusual for old bones to be disturbed when new graves were being dug. These bones would be removed from the ground to make space for newly-buried corpses, and stored instead in the churchyard’s charnel house.

At this time, there was a belief among Roman Catholics that one’s resurrection at the End of Days was dependent on the survival of the physical body (at the very least, the skull and the thigh bones – the most robust bones in the human body) – cremation was not permitted. Moving the disturbed remains to the charnel house ensured that they remained on consecrated ground to await resurrection at the End of Days.

This building in Spitalfields was used both as a charnel house and a chapel – the upper floor was the cemetery chapel, while the space below was the charnel house where old bones were stored when they were disturbed by the digging of new graves. The image above shows that the charnel house’s doorway led into a deeper room, its floor six to eight feet below the level of the doorway. The remains of arches can be seen, which would have supported the ceiling above. When in use, this space would have been packed full of bones.

Following the Protestant Reformation that began in the 1530s, charnel houses fell out of use in England and many were demolished or repurposed, their sad contents reburied or otherwise disposed of. As we’ve explored in the past here at Flickering Lamps, Bunhill Fields was where cartloads of bones from the huge charnel house at St Paul’s Cathedral were dumped in mounds, and the gloriously macabre ossuary in Kent at St Leonard’s, Hythe, is made up of centuries-old bones that were moved to the church’s crypt when its charnel house was taken out of use.

The Spitalfields charnel house was not immediately demolished after the dissolution of St Mary Spital in 1539, although it’s likely that the bones residing in the charnel house were removed and reburied elsewhere. While some other parts of the priory, including the church building, were dismantled (lead from the priory roof was used to repair the roof at Westminster Hall). The chapel above the charnel house was used as a secular building before being demolished in about 1700. The charnel house itself was filled with soil, and new buildings were constructed above it. These buildings were in turn replaced by houses and market buildings, which were demolished to make way for the office development that led to the charnel house’s rediscovery in 1999.

The Spitalfields we know today began to develop in the 17th Century, when the fields and market gardens that had characterised the area since the closing of the priory began to be replaced with new streets and houses. This marked the beginning of Spitalfields’ role as a centre of the textile industry – the people who moved into the new homes were silk weavers, many of them Huguenot refugees from France. In the 19th Century, many Jewish families settled in the area, and in the 20th Century Spitalfields became home to a large Bengali community. The 17th Century also saw the establishment of Truman’s Brewery and the Spitalfields Market. The fruit and vegetable market endured until the end of the 20th Century, and it was at this time that redevelopment prompted the large-scale archaeological surveys of the former priory buildings and its burial ground. The forgotten charnel house was excavated, retained and incorporated into the newly laid out Bishops Square in the early 21st Century, and curious visitors can now take the steps or lift down to view a unique survivor from medieval Spitalfields, while all around them rise the glass- and steel-clad towers of modern London.

Visitors to the charnel house today encounter two bronze figures; an art installation by David Teager-Portman that was unveiled in 2014. The two figures are called ‘Choosing the Losing Side’ and ‘The Last Explorer,’ and a little plaque close by explains that they “represent the history of figurative representation.” A greenish female figure crouches over a red figure that seems swaddled and wrapped in the manner of an ancient Egyptian mummy. I felt that the presence of these figures enhanced the atmosphere of the site, adding something haunting and melancholy to the space. In addition, several coloured plaques on the wall opposite the ruins show the history of Spitalfields as a public space. This installation, by Martin Donlin, recounts the history of Spitalfields through its relationship with public spaces – different plaques talk about faith, the pulpit cross (which once stood in the burial ground at St Mary Spital), performance, burial and others. Without the presence of any bones, the ruins of the charnel house could simply be seen as just a medieval building, but the bronze figures and plaques delving into the history of the area give the ruins additional context and atmosphere.

Although the charnel house is in fact the oldest remaining building in the whole borough of Tower Hamlets, its ruins reside in Bishops Square with little fanfare. Redevelopment has obliterated many historic buildings and spaces in London, but the survival of the charnel house and its preservation and display to the public is an example of how London’s heritage can coexist with modern development. Visitors to the charnel house get a rare glimpse of the past use of this area – not a bustling market, but a place of rest and recovery, and of burial.

The Spitalfields Charnel House is located on Bishops Square, E1.

References and further reading

FHW Sheppard (ed) – “The Priory of St Mary Spital,” Survey of London: Volume 27, Spitalfields and Mile End New Town, London, 1957 (pp21-23)

Don Walker – Excavating Spitalfields – the story of a global disaster, Archaeology in Marlow, 17th October 2013

Reading the bones: Spitalfields’ human remains – Current Archaeology, 6th August 2012

Jonathan Milohnić – St Mary’s Spital Cemetery, Medieval London

London’s volcanic winter – Current Archaeology, 6th August 2012

Mass grave in London reveals how volcano caused global catastrophe – The Guardian, 5th August 2012

Inside Spitalfields’ Oldest Building – Spitalfields Life, 1st July 2015

In the Charnel House – Spitalfields Life, 25th February 2019

Conservation in Action – Spitalfields Blog

House of the medieval dead lurks in lawyers’ basement – The Guardian, 8th July 2005

Secrets of the charnel house are brought to light – Daily Telegraph, 11th July 2005

Jane Sidell, Christopher Thomas, Alex Bayliss – “Validating and improving archaeological phasing at St Mary Spital, London,” Radiocarbon 49 (2), 2007, pp593-610

Don Walker – “Mass Burials from St Mary Spital, London,” lecture given at Gresham College, 12th October 2015 (PDF file of transcript can be downloaded)

Prof. William Ayliffe – “Medieval Hospitals of London,” lecture given at Gresham College, 7th April 2008 (PDF file of transcript can be downloaded)

This is fascinating. I worked in the City and particularly Old Broad Street and Bishops gate for many years and was oblivious to all of this. I ought to be ashamed as my late brother was an archaeologist! I live in Asia now but would like to go back and visit Spitalfields if I am ever in London again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article. I only had the vaguest idea about this place, but have now noted it for a future wander round when next in the Smoke!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great story, very interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this most interesting article. I think some of my ancestors lived in this area and now I’m a bit wiser as to maybe why given that it was a place for textle workers. I think they were weaves originally from Scotland so may have moved here for trade.

LikeLike

My father was born in a house almost directly above this excavation. The street, almost entirely occupied by Jewish immigrants, was part of a multi-storey terrace first occupied by Huguenot weavers with large attics as workshops. Many are still standing in streets around Hawksmore’s church. One wonders what was discovered [and discarded] when deep basements were created and much later when the rows were cleared for an extension to Spitalfields market before the war.

LikeLike