Not too far from where musician Jim Morrison is buried in Paris’ Père Lachaise cemetery stands an imposing monument that often gets overlooked by those set on finding Morrison’s memorial. It stands much taller than the graves around it, and on each corner winged skulls leer down at passers-by. It’s a superb monument, full of interesting details and rich imagery, and the man it commemorates lived a fascinating life.

This wonderful monument marks the grave of Étienne-Gaspard Robert, sometimes known by his stage name of Robertson. He was born in Liège, Belgium in 1763 and died in Paris in July 1837. On his tomb three words boldly describe his career: PHYSIQUE, FANTASMAGORIE, AEROSTATS.

Physique

The son of a merchant, Étienne-Gaspard Robert was fascinated by science from a young age and studied physics at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, becoming a professor specialising in optics. His work with optics would later be extremely useful for his theatrical career, but in 1791 Robert left Belgium and moved to Paris, intending to pursue a career as an artist.

Fantasmagorie

After his move to France, Robert began developing the show that was to make him famous: the phantasmagoria. Robert didn’t actually invent phantasmagoria but it was his shows that helped to bring the phenomenon to a global audience. The magic lantern, which made phantasmagoria possible, had been developed in the 17th Century. The magic lantern was a projector, with light being shone onto a mirror in order to project an image onto a surface nearby.

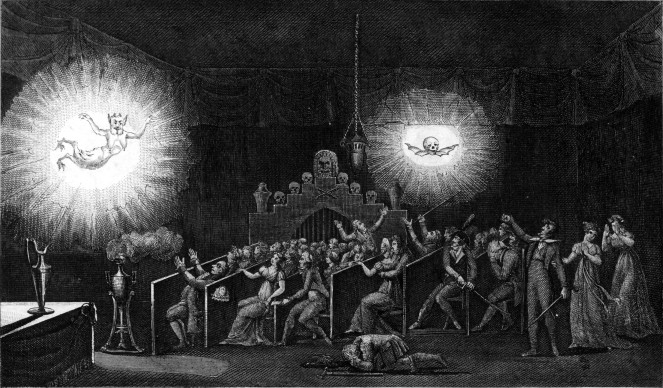

The first person to use magic lanterns to project frightening images was a German coffeehouse-owner called Johann Georg Schröpfer. Schröpfer’s coffeehouse was the venue for seances that Schröpfer and his associates would hold, with concealed magic lanterns being used to project images of ghostly figures. These seances were a multi-sensory experience: smoke and incense were used, as well as eerie music and strange sound effects, and those attending the seance were often, unbeknownst to them, given drugged food or punch. Schröpfer died by suicide in 1774, but his seances had caused quite a stir and a number of books and pamphlets were published discussing his techniques and possible magical powers.

Another pioneer of phantasmagoria was Paul Philidor, a German who was inspired by the work of Schröpfer and who developed Schröpfer’s ideas to make a show for a larger audience. He first performed in public in Berlin in 1789, calling his show “Schröpferesque Geisterscheinings” (Schröpfer-style ghost appearances). He later took the show to Vienna, and then to Paris in 1793, which is where Étienne-Gaspard Robert saw his performance and was inspired to produce his own phantasmagoria.

Philidor’s show in Paris proved to be controversial. It included depictions of well-known French revolutionaries, such as Robespierre, as devilish figures, and Philidor was arrested after it was claimed that he had depicted the spirit of the executed King Louis XVI ascending to heaven.

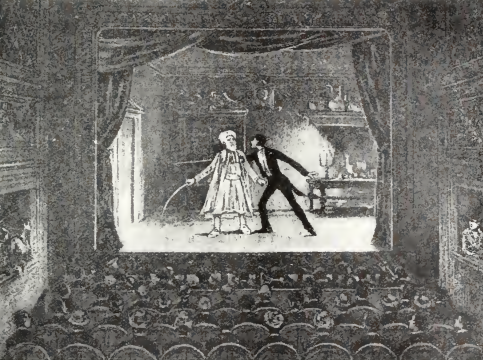

Inspired by the work of Schröpfer and Philidor, Robert took the basic technology of the magic lantern and applied his knowledge of optics to it so that the projected images could expand or shrink in size. Robert secured a patent for a magic lantern on wheels – the Fantascope – in 1799, which used the same basic technique as a modern zoom lens. It was Robert’s technical excellence that really set his show apart. Skilfully painted slides were used for the images of ghouls and phantoms (with the likenesses of well-known people sometimes used), with the rest of the glass slide being painted black so that the projected images would appear to be floating in mid-air. The use of smoke and mirrors helped to conceal the projectors, and Robert employed a cast of actors and ventriloquists to provide music, movement and voices to add to the spectacle.

Robertson’s Phantasmagoria debuted in January 1798 in a Paris that had been rocked to the core by the French Revolution and the brutal Terror that followed it, and Robert’s show was so scary, so unsettling, that many who attended truly believed that they had seen ghosts. The show caused such a stir, and frightened so many people, that it was shut down by the authorities. Undeterred, Robert took his show to Bordeaux while the furore died down. On his return to Paris, Robert chose a suitably creepy new location for his show – the derelict Convent des Capucines. This unsettling location added to the immersive nature of the show, with visitors entering the venue through a graveyard and taking their places in a room draped with black velvet.

On one side of Robert’s tomb is a carved image of the phantasmagoria. When I first saw this image, I wondered if it was a danse macabre, but in fact it depicts an audience at one of Robert’s show being frightened by images of skeletons and monsters. Some of the audience members are flinching away from the ghouls; others cover their faces.

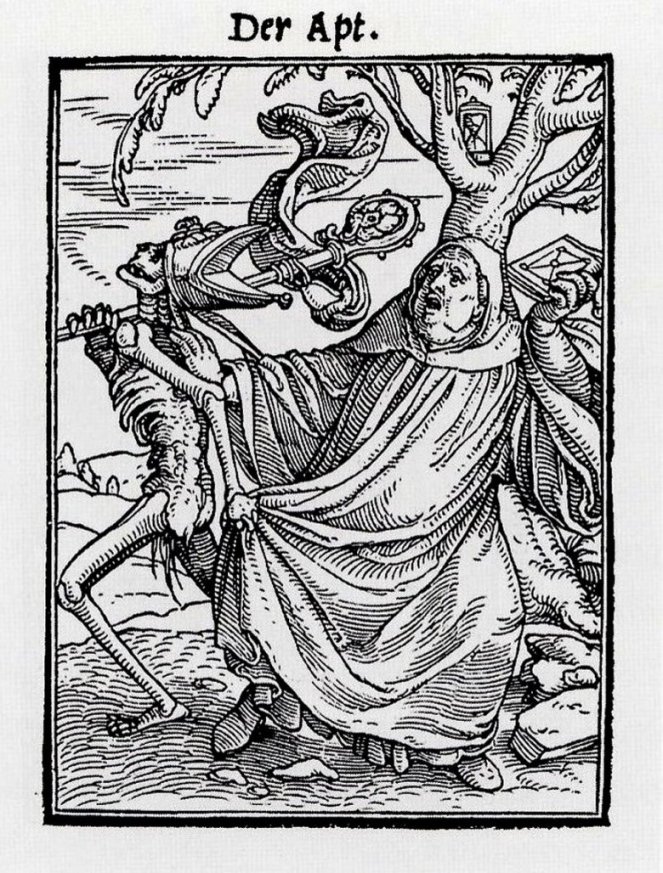

Some of the imagery used in Robert’s shows was in fact inspired by the medieval danse macabre images that featured skeletons and other ghoulish figures, in particular a series of woodcuts called “The Dance of Death” produced by Hans Holbein the Younger in the 1520s and published in 1538.

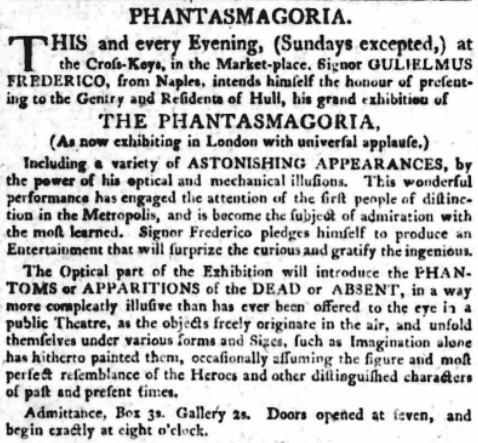

The success of shows by Robert, Philidor and others ushered in a period of huge popularity for the phantasmagoria both in Europe and North America. Unlike the early shows, where audiences often believed that they were seeing spirits of the dead, most phantasmagoria shows were marketed as illusions and entertainment, with the scientific side of the visual tricks being emphasised. The newspaper advertisement shown below is for a phantasmagoria in the English city of Hull in 1802, presented by an Italian, Gulielmus Frederico.

Paul Philidor, the performer whose work inspired Robert, took his show to London, where he became a permanent fixture at the Lyceum Theatre on the Strand in 1801. Perhaps because of the controversy that had dogged his shows in Berlin and Paris, he – like many others performing similar acts – made it clear that the show was scientific in nature and for entertainment.

Aerostats

Robert’s Phantasmoragia shows enabled him to travel around Europe and North America and whilst on these travels he was able to indluge in another passion – flying balloons. When he had first moved to Paris, Robert had attended lectures by the ballooning pioneer Jacques Charles, who – along with Nicolas Marie-Noel Robert (no relation to Étienne-Gaspard) – had been responsible for the first manned flight of a gas balloon in 1783.

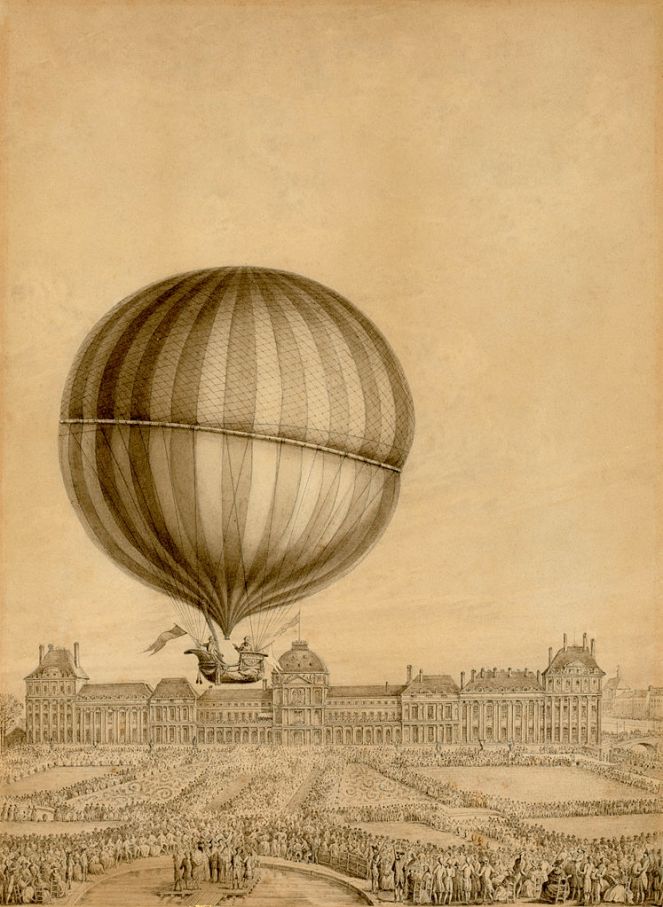

Étienne-Gaspard Robert made a total of 59 balloon flights, including a flight in 1803 where he set an altitude record, and a famous flight in Denmark in 1806 where huge crowds (including members of the Danish royal family) gathered to watch him ascend from Copenhagen and fly all the way to Roskilde. Robert often carried out scientific experiments whilst in flight, studying cloud formations, making measurements on barometers and thermometers and testing parachutes at different altitudes. He also designed a number of the balloons that he flew in. A bas-relief on his grave shows a balloon in flight, while people on the ground look on.

Robert’s impressive memorial is a wonderful example of a grave that tells the story of the life it commemorates. He must have died a wealthy man to have his grave marked by such a large and ornate monument. The macabre imagery of the winged skulls ties in with the phantasmagoria shows and Robert’s love of the macabre, while the two bas-reliefs depict his passion for illusion and aviation. Even in a cemetery as grand and fascinating as Père Lachaise, Robert’s outstanding memorial invites the visitor to stop, observe and reflect on the incredible images it depicts.

References and further reading

Allison Meier – Robertson’s Fantastic Phantasmagoria, an 18th Century Spectacle of Horror, Atlas Obscura, 9th May 2013 http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/robertsons-fantastic-phantasmagoria/

Magic Lantern History http://www.magiclantern.org.uk/history/history01.php

Deac Rossell – The 19 Century German Origins of the Phantasmagoria Show http://www.academia.edu/4609248/The_19_Century_German_Origins_of_the_Phantasmagoria_Show

The true origins of screen horror – Grand Illusions http://www.grand-illusions.com/articles/lantern_of_fear/

Phantasmagoria: How Étienne-Gaspard Robert terrified Paris for science – Skulls in the Stars, 11th February 2013 https://skullsinthestars.com/2013/02/11/phantasmagoria-how-etienne-gaspard-robert-terrified-paris-for-science/

Another fascinating post — well done!

LikeLike

This person is significant to science. Its nice to remember the experiments that constitutes our

present state of existence. I thank you. Bruce

LikeLike

A genuine “Flickering Lamp” this week! Fascinating, as always!

LikeLike

I love Phantasmagoria, and how I wish I could attend that one at the Convent des Capucines! It sounds amazing! It is a fittingly awesome tomb for someone who sounded like an awesome man. Fascinating post, as always! 🙂

LikeLike

Another wonderful piece of offbeat history! Thank you!

LikeLike

Fascinating story and fascinating monument. I’m wondering though why somebody standing at the back of the audience in the phantasmagoria scene looks like an ancient Greek – wearing a helmet and with a beard. Do you have any ideas what that was about? Is that a contemporary military uniform?

LikeLike

Thank you! I am not sure about the military uniform. I’m no expert but it does not look contemporary – perhaps this figure is one of the actors involved with the show?

LikeLike

I used to be a guide in Père Lachaise. The figure standing on the barrel on the left is Benjamin Franklin who was in Paris at the time the balloon ascended.

LikeLike